Colorado justices conflicted about using views on police bias to remove jurors of color

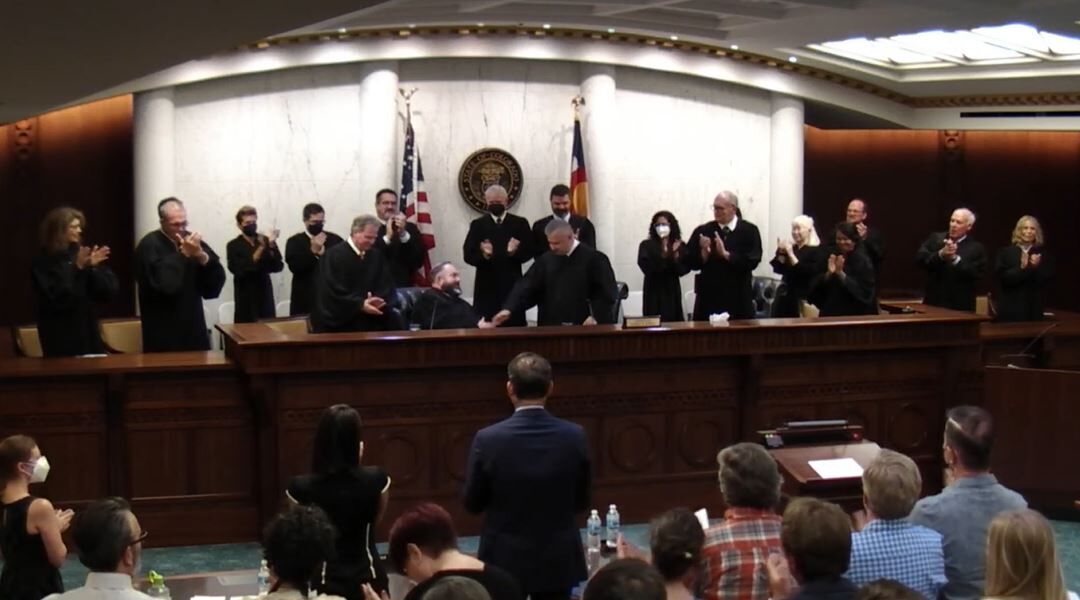

For two hours on Tuesday, the Colorado Supreme Court grappled with a question that could significantly affect the composition of juries going forward: If a juror of color, based on her experiences, says that bias in policing exists, would removing that person from the jury pool be tantamount to dismissing her because of her race?

Previously, in a pair of cases out of Arapahoe County, the state’s second-highest court overturned the defendants’ convictions because prosecutors dismissed, or “struck,” two women of color from the jury pool. Although the prosecutors explicitly justified the strikes with concerns about the women’s attitudes toward police, the Court of Appeals concluded those views were linked to race.

During oral arguments, Justice Richard L. Gabriel warned that if prosecutors could strike jurors of color whose negative experiences with police were informed by their race – or the race of their friends and family – anyone who speaks about a “driving while Black” encounter could effectively be barred from serving on criminal juries.

“I dare say a large percentage of the people of color in this country know of someone who has had this experience,” he said.

Under longstanding U.S. Supreme Court precedent, intentional race-based discrimination in jury selection is unconstitutional. Normally, parties may exercise “peremptory strikes” of jurors without citing a reason. But when a prosecutor tries to dismiss a juror of color, the defendant may raise a “Batson challenge,” named after the Supreme Court’s Batson v. Kentucky decision. Such a challenge forces the prosecutor to justify the removal with a “race-neutral” reason.

The challenge proceeds in three steps. First, the defense must state a plausible case that a juror is being removed on account of their race. Second, the prosecution must offer a race-neutral explanation. Finally, the trial judge analyzes whether discrimination is likely happening.

The current cases before the state Supreme Court focused on whether a juror’s potential bias against police is a race-neutral explanation when there is a link between the juror’s race and her views toward law enforcement.

Several justices noted any connection to race could be sorted out during step 3, when a trial judge assesses the credibility of the prosecutor’s justification. However, Justice Melissa Hart suggested trial judges, in reality, may find it difficult to sustain a Batson challenge at that final stage.

“I don’t come from a criminal law background. I come from an employment discrimination background,” she said. “And at step 3 in employment discrimination, which looks very similar to step 3 in Batson, what you’re saying is a race-based reason was used. Which people hear as: ‘You are a racist.’ So, is that the crux of the problem here?”

Justice William W. Hood III also worried whether Batson challenges have “any teeth” if trial judges treat views informed by a juror’s race as race-neutral.

“We’re human beings and we’re reluctant to be seen as even implicitly pointing the finger at someone and accusing them of acting in a way that seems racist,” he added.

Steps to a Batson challenge

If the prosecution attempts to strike a juror of color and the defense raises an objection based on Batson v. Kentucky, the challenge proceeds in three steps:

Step 1: Is there a plausible claim that the strike is based on race?

Step 2: Does the prosecution have a race-neutral reason justifying the strike? It does not need to be persuasive at this stage.

Step 3: Based on the credibility and plausibility of the reason, is purposeful racial discrimination motivating the juror strike?

Appeals court draws line on bias

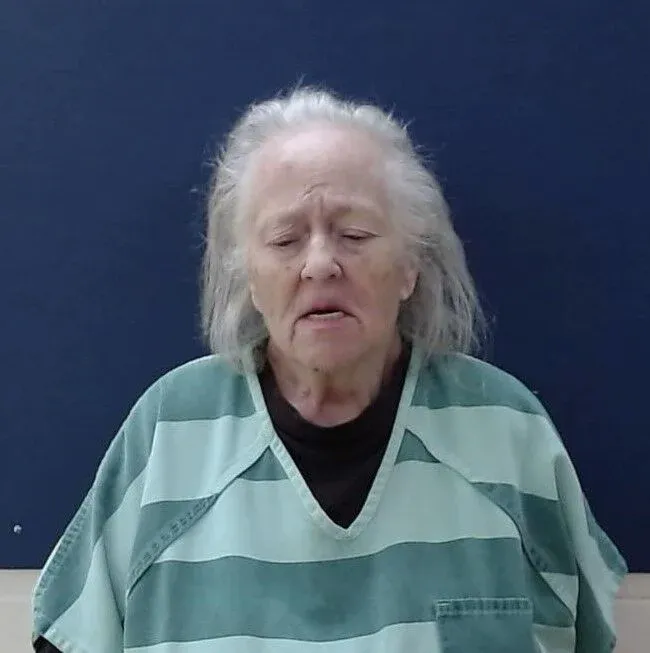

In the first case, Arapahoe County jurors convicted Raeaje Resshaud Johnson of multiple domestic violence-related offenses. The jury questionnaire asked whether jurors or their friends or family ever had bad experiences with police. A Black woman, identified as Juror M, wrote, “Yes. Many cases where cops are disrespectful due to certain racial identities.”

Neither party asked Juror M about her response. When prosecutor Neillie Fields moved to strike Juror M and the defense raised a Batson challenge, Fields became offended and said it was “tantamount to an accusation of picking jurors based on race.” She then cited Juror M’s answer on the questionnaire.

“It’s clear, based on her questionnaire, that she’s experienced racism in the past,” the defense attorney responded. “I believe she’s experiencing racism as a juror by taking her off this panel.”

District Court Judge Ben L. Leutwyler permitted Fields to strike Juror M. However, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals reversed Johnson’s convictions. It issued a precedent-setting opinion, concluding prosecutors may not remove Black jurors solely for having negative experiences with law enforcement that were informed by their race.

Then-Judge Michael H. Berger dissented. Although he agreed Leutwyler mishandled the Batson challenge, Berger was more concerned about prosecutors being forbidden from striking jurors who will potentially distrust police witnesses in criminal cases.

“I fear that the majority opinion will reasonably be read by lawyers and lower court judges for the proposition that once a prospective juror expresses the belief (held by many) that police do not treat minority persons equally, the prospective juror becomes immune to a peremptory challenge,” he wrote.

In the second case, Arapahoe County jurors convicted Sterling Dwayne Austin of murder. During jury selection, the defense asked whether any juror felt they were the victim of “racial prejudice.” One woman, Juror 32, said a sheriff’s deputy made her feel uncomfortable during a traffic stop, ultimately issuing her a ticket that noted her race, incorrectly, as “White.”

Juror 32 elaborated that the experience made her think about “projects that I used to do in high school” to reform the Denver Police Department’s racial profiling practices at the time.

Prosecutors Casey Brown and Victoria Klingensmith moved to strike Juror 32, citing her potential bias against Denver police officers who were witnesses in Austin’s case, plus Juror 32’s “negative experiences” with the Denver Police Department. Then-District Court Judge Patricia Herron denied the Batson challenge without elaboration.

Once more, a panel of the Court of Appeals overturned Austin’s conviction, finding the “negative experience (Juror 32) described was clearly based on her race.”

With both cases before the Supreme Court, a collection of legal groups that included the ACLU of Colorado and the bar associations for Hispanic, Asian, South Asian and Black attorneys urged the justices to uphold the Court of Appeals’ decisions. They cited recent research about Batson challenges from Berkeley Law’s Death Penalty Clinic showing prosecutors in California struck jurors 34% of the time for distrust of police, with appellate courts reversing in less than 3% of cases.

“Black and other jurors of color are disproportionately more likely to be struck from juries for purportedly neutral reasons that are inextricably tied to race, such as experience with the criminal legal system, or due to implicit or unconscious racial biases,” the groups wrote. “Such disproportionate exclusion affects trial outcomes and threatens the legitimacy of, and public confidence in, the legal system.”

When is a reason race-neutral?

During oral arguments in Johnson and Austin’s cases, two justices spoke at length, from opposite sides, about how to view jurors’ racially informed attitudes toward police.

“At step 2 what we’re looking at is: Was the reason provided race-neutral? And why can’t the prosecutor say, ‘Judge, this person is distrustful of police officers. I don’t care the reason why they’re distrustful. They are distrustful’,” said Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. “The DA’s gonna have cops as witnesses. You’ve got someone here who appears to not like cops for whatever reason. Why isn’t that OK?”

It becomes a problem, responded defense attorney Tanja Heggins, when a seemingly race-neutral reason is a proxy for the juror’s race.

“We are applying Supreme Court precedent here. This wasn’t our rule,” Samour continued, referring to Batson itself. He added that the time to consider whether the prosecution’s explanation implicates the juror’s race is at step 3.

“I was a trial court judge for 11.5 years,” said Samour. “I agree that it’s not the most comfortable feeling to sustain a Batson challenge because of what that conveys. But … it’s the Supreme Court that has set that bar low at step 2 and has said, ‘Hey, all the prosecution has to do is present a reason that’s facially valid.'”

Gabriel, who sits next to Samour, countered that it would be problematic if prosecutors could avoid asking jurors of color directly about their potential bias, instead striking them because they answer truthfully about having negative experiences with law enforcement.

“It seems to me we have to make an inference from ‘I have experience of disrespect by a police officer’,” he said, “to ‘that means bias against the police.’ And I’m concerned because I would expect many, many people of color in this country, very sadly, would say yes to that question. Which doesn’t necessarily mean they have bias against any officer.”

“Every experience is inextricably linked with race. I don’t know how you separate it,” said First Assistant Attorney General John T. Lee.

“If the prosecution avoids saying the word ‘race,’ we’re safe?” Gabriel wondered. “Step 2 needs to mean something more than just, did the prosecutor mouth the wrong word?”

Potential reforms

Lurking in the background of the arguments was a proposed change to the rules of criminal procedure that is pending before the state Supreme Court. The proposal, which originated in one of the court’s rules committees, is intended to expand Batson‘s protections by deterring prosecutors from striking jurors of color for reasons that, while correlated with race, are not explicitly racial.

There would be new hurdles, for example, to dismiss a juror of color for living in a “high-crime neighborhood,” having prior contact with law enforcement or expressing distrust of police. The Supreme Court has elected to hold over any decision on the proposal until it rules on Johnson and Austin’s cases.

During a public hearing last year, district attorneys voiced opposition, deriding it as “affirmative action in jury selection” and warning that juries would become skewed with people who admit to distrusting law enforcement. Some of the same concerns surfaced during oral arguments this week.

“The prosecution’s right to have a fair trial or a fair shot at prosecution cannot trump an individual’s constitutional rights here to not be kicked off of a jury because of their race,” said defense lawyer Joseph Chase.

“Even to the extent it leads to a biased juror sitting on a jury?” responded Justice Monica M. Márquez. “I feel like what you’re setting up is very asymmetric.”

Multiple attorneys and Samour signaled their openness during arguments to eliminating peremptory challenges altogether, as Arizona’s Supreme Court did in 2021. However, taking the same path in Colorado would require the legislature to act.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter raised a potential workaround to lawyers relying on brief, even vague responses on juror questionnaires to make decisions about who to strike.

“Do you think,” she wondered, “there are things trial courts could be doing in terms of jury questionnaires that would hep clarify some of these issues?”

Lee, of the attorney general’s office, took a long pause to think about the implications.

“Possibly,” he said.

The cases are People v. Johnson and People v. Austin.