Appeals court upholds restrictions on court access for man who threatened 2 judges

Colorado second-highest court agreed last month that the restrictions imposed upon a man who harassed multiple Western Slope judges did not unconstitutionally infringe upon his right to access the courts.

As part of his probationary terms for the offense of retaliating against a judge, Brett Andrew Nelson was required to obtain a court’s permission before filing any legal documents, and was generally prohibited from contacting any judge or court staff himself.

Nelson challenged those conditions as violating the Colorado Constitution, which provides that courts “shall be open to every person.”

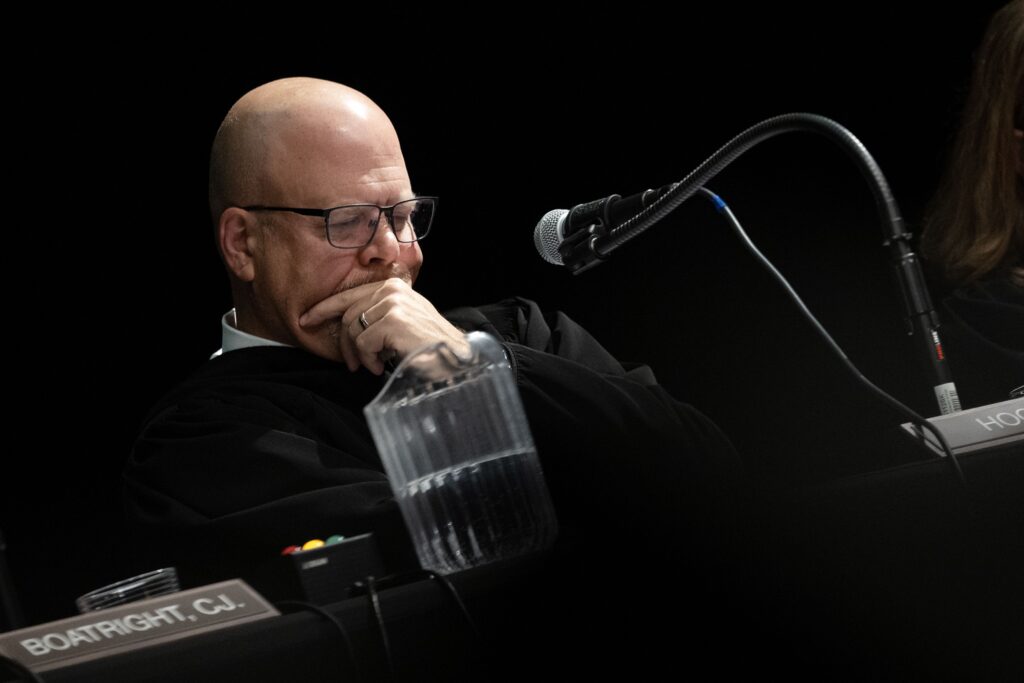

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals disagreed that the limitations on Nelson’s access to the courts and court personnel were unjustified, in light of his conduct.

“Limiting Nelson’s unfettered access to courts and court employees does not prevent him from representing himself; it prevents future instances of the criminal behavior for which he was sentenced,” wrote Judge Dennis A. Graham in the Dec. 14 opinion.

CBS News reported last year that a state grand jury indicted Nelson after he filed numerous unfounded assertions of power or demands for money against judges, law enforcement officials and even his alleged victims. The charges against Nelson included forgery and extortion.

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office announced at the time that Nelson was using “sovereign citizen-like tactics.” Sovereign citizens believe they are not subject to the laws and regulations of an allegedly-illegitimate government, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation has labeled the movement domestic terrorism. Sovereign citizen tactics include making claims that they have law enforcement authority, and harassing entities with so-called self-executing contracts.

In Nelson’s case before the Court of Appeals, he made multiple threatening phone calls to Gunnison County Court Judge Ashley M. Burgemeister, who had overseen multiple cases involving Nelson, as well as to her husband. Nelson called Burgemeister derogatory names, said he would exact retribution against her and alleged she owed him $5 million based on a dubious arbitration agreement.

Around that time, Nelson also made 34 phone calls to District Court Judge D. Cory Jackson, who had also handled cases involving Nelson, and to Jackson’s family. Once again, Nelson threatened Jackson and demanded $5 million.

In a plea deal, Nelson received four years of probation for the charge of retaliating against a judge. The probationary terms included restrictions on Nelson’s future ability to file lawsuits — he previously filed dozens in Colorado’s state and federal courts — and on his contact with court personnel.

“To me, when you undermine the system, you do harm to everybody that’s part of the system. And you’ve done harm. And it’s not going to be tolerated anymore,” retired District Court Judge Kenneth M. Plotz told Nelson at sentencing.

On appeal, Nelson argued any restrictions affecting his constitutional rights required there to be compelling circumstances and no less restrictive option. He believed the probationary conditions were not relevant to his harassing phone calls to judges.

“There is no reasonable or articulated nexus between a restriction on filing official court documents or official records with a clerk and recorder and phone calls,” wrote attorney Jeffrey C. Parsons.

The Court of Appeals panel disagreed. Previous court decisions have established that the need for restrictions can be “self-evident,” and the panel believed Nelson’s threats, retaliation and improper use of the judicial system justified the probationary terms.

“Such conditions limit his ability to file meritless pleadings or contact court staff about matters unrelated to his ongoing cases, while allowing him to remain involved in the proceedings,” wrote Graham, a retired judge who sat on the panel at the chief justice’s assignment. “Anything less restrictive — permitting Nelson to submit court filings without attorney or judicial oversight or contact judicial staff about matters beyond active cases — would enable him to engage in the same conduct that resulted in the charges for which he is serving his probation sentence.”

The case is People v. Nelson.