Jury to hear ex-La Plata County jail nurse’s retaliation case under new Colorado whistleblower law

A jury will decide whether a former nurse in the La Plata County jail experienced retaliation and discrimination under a Colorado law enacted early in the COVID-19 pandemic to protect whistleblowers who raise public health concerns in the workplace.

Last month, U.S. District Court Senior Judge Lewis T. Babcock acknowledged no other courts had yet interpreted the state’s Public Health Emergency Whistleblower Act of 2020. However, he determined jurors could ultimately find the county jail’s medical contractor, Southern Health Partners, Inc., took unlawful action against Allison Mitchell after she complained about her coworkers’ refusal to follow public health protocols, such as masking.

“I agree with Plaintiff that she has provided evidence that raising her concerns and/or opposing unlawful practices related to health and safety in the workplace,” Babcock wrote in an Oct. 12 order, were a “substantial or motiving factor in various resulting adverse employment actions by SHP.”

SHP hired Mitchell to work in the La Plata County jail at the outset of the pandemic in March 2020. She resigned a year later. According to the parties’ evidence, there were repeated conflicts between Mitchell and the other medical personnel – largely stemming from Mitchell’s desire to follow the required masking and distancing protocols.

When her coworkers did not follow suit – and her manager enraged the county by showing up to work having tested positive for COVID-19 – it was Mitchell who experienced negative consequences from her employer.

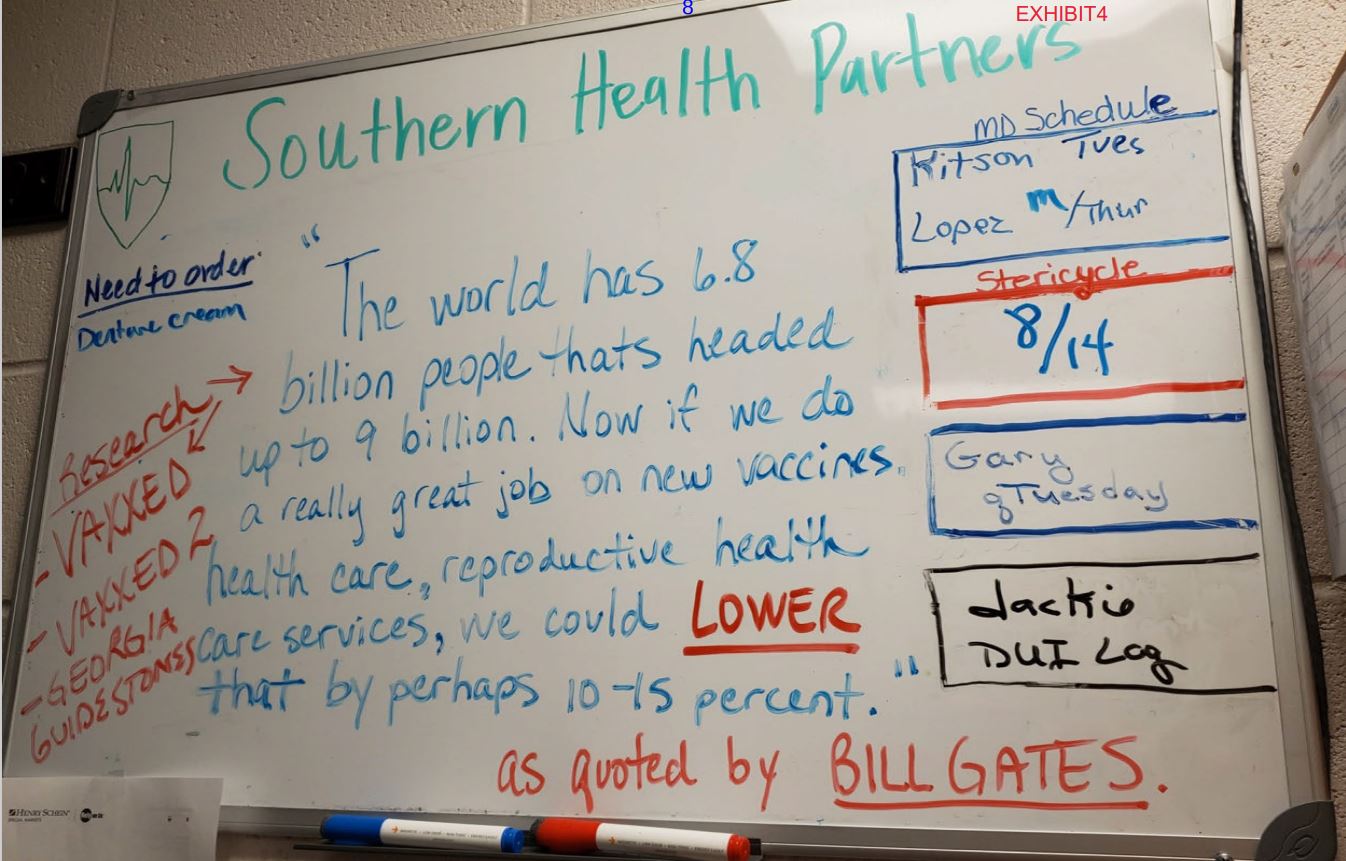

During Mitchell’s employment, she encountered anti-masking fliers and references to vaccination conspiracies scrawled on a whiteboard inside SHP’s room in the jail. One coworker came to work with a menstrual pad on her face, which Mitchell interpreted to be a mockery of the government’s health orders.

The medical team administrator, Amber Fender, also complained to the sheriff that having detainees wear masks would “potentially cause more illness” and that policymakers would soon understand “the negative effects on one’s health” from masking. At one point, when Fender showed up to the jail after testing positive for COVID-19, SHP’s vice president of operations argued against removing Fender from her job, saying she had no “ill-intent.”

“Unfortunately, this behavior appears to be part of an ongoing failure by Ms. Fender to appreciate the seriousness of the illness, its potential impact on staff and the Facility’s population and the legal requirements/expectations placed upon detention facilities,” responded La Plata County Attorney Sheryl Rogers in demanding Fender’s removal.

Mitchell raised her concerns on multiple occasions, including in a lengthy report in December 2020. Mitchell wrote that she was concerned about retaliation and a hostile work environment, but “the state mandate and the jail policy is that every person is supposed to wear a mask when indoors, sharing an office, and around other people.”

Days later, Stephanie Self, the vice president who previously defended Fender’s behavior, allegedly told Mitchell to “let it go.”

In March 2021, SHP suspended Mitchell for mistakenly substituting a detainee’s medication. A company executive wrote in an email that Mitchell had likely made an error, but the bigger problem was Mitchell’s “attitude overall.”

Mitchell resigned on April 1, attributing her decision to the “retaliation I have experienced after speaking out against this company’s failure to follow the basic public health guidelines in our office.”

She filed suit under the Public Health Emergency Whistleblower Act, which Colorado’s legislature enacted to shield whistleblowers from retaliation when they raise concerns about employers who violate public health orders.

SHP moved for summary judgment, asking Babcock to resolve the case in its favor without a trial. The company argued it took COVID-19 “very seriously” and that Mitchell’s concerns did not rise to the level of protected whistleblowing. It pointed to Mitchell’s statements indicating she was not asking her coworkers to wear masks – statements Mitchell admitted she made in order to avoid a “virulent reaction.”

Instead, Babcock agreed SHP would face trial for three alleged violations of the whistleblower protection law. As for Mitchell’s claims of discrimination and retaliation, Babcock concluded Mitchell’s December 2020 report warning about the need to follow public health protocols amounted to protected activity. That report, plus her other complaints, were followed by negative consequences, including Mitchell’s suspension.

“While I agree that SHP has provided sufficient evidence of a legitimate reason for Plaintiff’s suspension,” Babcock wrote, “Plaintiff has provided evidence that the discipline she received (a three-day suspension for a first-time documented offense) was excessive,” potentially suggesting SHP had other motivations at the time.

Finally, Babcock agreed with Mitchell’s claim that SHP appeared to violate the whistleblower law by enforcing an informal policy of suppressing complaints about workplace safety violations. A jury could view the directive to “let it go” as an indication the company wanted to discourage Mitchell from reporting her concerns, Babcock concluded.

The trial date has not been set. Last week, the case was transferred to U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney, who will handle the remainder of the proceedings.

The case is Mitchell v. Southern Health Partners, Inc.