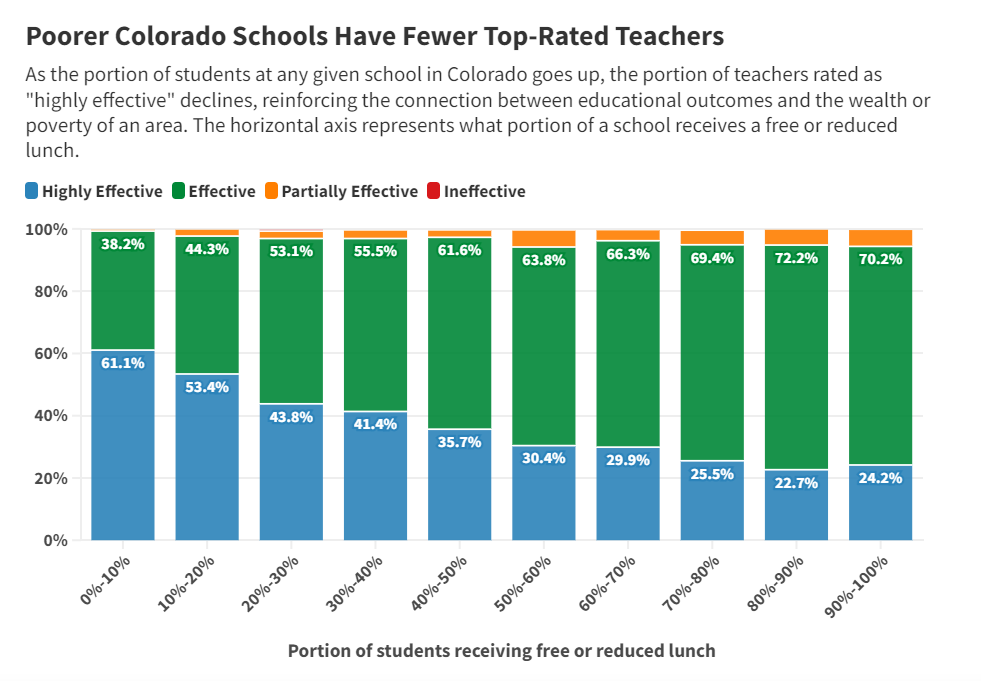

Colorado’s poorest schools have fewer highly effective teachers than the wealthiest schools, raising equity concerns

Colorado’s “highly effective” teachers are unequally distributed across its public schools, according to a Denver Gazette analysis of the state education department’s teacher evaluation data.

The poorer a school is in Colorado, the more likely it is to have fewer “highly effective” teachers, while top-rated teachers are mostly concentrated in the state’s wealthier schools, the analysis from the Gazette, a sister publication of Colorado Politics, showed.

Although some researchers say the metric is flawed to begin with, the findings reinforce the link between educational outcomes and families’ level of poverty or wealth.

For every 5-percentage point increase in the number of students receiving free or reduced lunch at a school – a widely accepted proxy for the school’s poverty level – the data suggests there will be a 2-percentage point decrease in the portion of teachers with the highest state effectiveness rating.

And while the statistical relationship between the two factors is modest for schools that fall into the broad middle of the poverty-wealth continuum, the correlation is notably stronger when focusing on schools at the extremes.

At the top of the wealth scale, in schools where fewer than 10% of students get a subsidized lunch through the National School Lunch Program, an average of 61% of teachers were given the “highly effective” rating in the most current data.

But at the other end of the spectrum, where at least 90% of students have their lunch paid for by the program, an average of 24% of teachers get the same top rating.

To get at the pervasive connection between wealth and educational outcomes in Colorado, the Gazette combined the most current educator effectiveness metrics (from the 2021-2022 school year), using the “overall effectiveness” ratings from every school for which the state makes data available, with the schools’ free and reduced lunch percentages.

The “highly effective” score is the top ranking a teacher can receive in the state’s teacher assessment system, which relies on classroom observation of professional practices and student academic growth.

The unequal distribution of the highest rated teachers occurs despite a teacher evaluation system adopted by Colorado that the Obama administration hoped would improve schools. And it’s a phenomenon that occurs in Denver Public Schools, one of the nation’s largest school districts, despite the district nearly two decades ago becoming one of the first in the nation to try to steer teachers to high poverty schools through a merit-pay program.

Colorado’s low childhood vaccination rates stoke fears of outbreaks

“Teacher quality effectiveness is consistently shown to be the number one in-school factor that predicts and affects student achievement and other long-term outcomes,” said Allison Atteberry, an associate professor of education and public policy with the University of Virginia and a research affiliate with the University of Colorado. “So, we think having access to a highly effective teacher is one of the strongest levers for improving outcomes for kids. Trying to figure that out is I think a top priority in basically every school district in every state, and it is an incredibly challenging one.”

Denver Public Schools’ merit pay program

A 2017 analysis by Atteberry, then an associate professor with the University of Colorado, did not find evidence that the Denver Public School’s professional compensation merit pay program — launched in 2005 and known as ProComp — caused teachers to transfer into high poverty schools, though there was some indication that the rate of teachers leaving hard-to-serve schools slowed.

Denver Public Schools tried to bolster ProComp in 2015 by creating an enhanced bonus-pay program – called the Highest Priority Incentive Program — to further incentivize teachers to tackle tough assignments in schools with the highest rates of poverty and high proportions of students of color and English language learners.

But a 2020 study Atteberry participated in further found no evidence that the 38 schools that participated in the high priority incentives had increased teacher retention or were able to attract teachers with higher job performance ratings through the yearly $2,500 bonuses for teachers.

‘Delay and obfuscation’: Denver schools’ pattern of response to records requests | ANALYSIS

The 2020 study, which examined the highest priority incentives between 2016 through 2019, concluded the teacher incentives may not have had an effect in part because they were small in comparison to the much larger bonuses of $30,000 paid to administrators, such as principals, at the participating schools. Administrative bonuses also weren’t linked to performance as they were for teachers, the study noted.

“This could have the unintended consequence of retaining school leaders who have received negative evaluations from the teachers,” according to the analysis. “If this has occurred, it could unintentionally result in the exit of teachers who are dissatisfied with their school leadership and for whom the bonus pay does not make up for perceived working conditions.”

Rob Gould, the president of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, said the highest priority incentives, which after 2019 rose to $3,000 annually for teachers, also were marred because it was difficult to understand why school district officials choose certain schools to participate.

“There wasn’t, like, any scientific way of doing it,” Gould said. “It was like there was literally a dartboard downtown they used. They just cobbled this thing together.”

Denver Public Schools agreed in collective bargaining to do away with ProComp in 2019 to help resolve a strike by Denver teachers.

The Denver school district three years after it got rid of ProComp agreed in collective bargaining to begin reallocating the $3.5 million annually spent on the high priority incentive program to other priorities, starting with the current school year. That money now is used primarily to bolster the pay of special education teachers and hard to fill positions like psychologists, social workers and nurses.

The Gazette found poorer schools in Denver are more likely to have “partially effective” teachers — the second to lowest ranking for teacher effectiveness — than wealthier ones.

Not many schools report having any teachers ranked as partially effective, which means drawing conclusions about teacher effectiveness based on the category is practically impossible. But The Gazette found 33 schools out of 201 schools in Denver have 10% or more of their teachers rated as partially effective, with a handful of the schools in the district having as many as one out of every four teachers rated that low. Of those 33 schools, 29 have more than 60% of their students qualify for subsidized lunches, the average subsidized lunch rate district wide.

Just two schools in Denver reported 5% of their rated teachers as ineffective. Those schools similarly had more of their students on subsidized lunch plans than the average for the district. None of the wealthier schools in Denver reported having 5% or more of their teachers as ineffective.

A superintendent tackles equity issues in Colorado Springs

Two districts in El Paso County – Colorado Springs District 11 and Academy District 20 – also show striking differences in teacher effectiveness ratings, with the wealthier Academy District 20 getting a greater share than Colorado Springs District 11, which has schools in some of the poorest areas of the city.

Pine Creek High School in District 20, one of the wealthiest schools in the state, has 57% of its teachers rated as highly effective. In contrast, Mitchell High School in District 11, where three out of every four students qualify for subsidized lunches, has just 3% of its teachers rated as highly effective.

That type of disproportionate distribution of highly effective teachers has become a top priority for Michael Gaal, a former colonel in the U.S. Air Force, who was hired in 2022 as superintendent for District 11 with a mandate to push change. When he was hired the district had five schools listed on the state’s turnaround designation for having among the state’s lowest student outcomes.

“Teaching is hard,” Gaal said. “Teaching students that are behind is even harder. Teaching students that are behind when you’re understaffed is almost impossible.”

After taking over as superintendent, Gaal reviewed data on teacher vacancies and concluded the district was having a harder time filling teaching jobs in the poorer southeastern part of Colorado Springs. Schools in that area of the district have a 6% monthly vacancy rate in teaching positions, triple the vacancy rate of schools in the wealthier western part of the district, he found.

The district once was the last school district in the area to hire principals and teachers, but Gaal has reversed the order and made sure the district is the first in line in the area to hire for those positions. He also pushed to increase the salaries of younger teachers by 20%, which he said ensures the district has the highest salaries in the area for younger teachers. Under his watch, the district has overhauled curriculum and increased visits from the central office support staff to the poorer schools.

“You can’t go half the year with somebody new to a classroom environment and then come in and say, ‘How’s it going?'” Gaal said. “So, I’ve personally been in 85 of the 115 classrooms with new teachers since the start of the school year. I said I’d get to them all in the first 60 days.”

Gaal wants the school board to add a new salary strategy, too, that will allow him to select 20 teachers of the highest achievement for additional salary raises of 20% if they agree to teach for 20 months in schools where students need skilled teachers the most. He believes each one of those teachers that gets placed will be a change agent that can push existing staff to new heights.

“You put the best lifeguard up when it’s stormiest when you’re at the beach,” Gaal said. “How do we get our strongest educators to see that the value is in moving the kids that need the most.”

So far, Gaal’s push is working. In one year, the five schools in the district that the state had designated for turnaround status moved off that designation. He’s full of additional ideas, including pushing for teachers to get reduced property taxes, which he believes would infuse the profession with an increase in honor and stature.

“We showed people that you can move a school in one year,” Gaal said.

Teacher evaluations differ among states

Colorado since 2010 has measured teacher job performance half by student academic growth and half by classroom observation on professional practices such as showing a strong understanding of content and delivering effective instruction.

Districts use various academic data, including standardized test scores of students, to measure academic growth of students, using state rules to guide them in how to do so. School districts choose the evaluators.

The Gazette limited its analysis of teacher effectiveness data to the 2021-2022 school year because during the COVID-19 pandemic teacher effectiveness rankings were not measured for one year and did not include student academic growth in another year. The Gazette analysis also was hampered because charter schools are not required to participate in teacher effectiveness rankings, though some do.

The data also has limitations because when there are five or fewer teachers at a school in a ranking category the state suppresses the data. Some teachers also do not participate due to timing issues the state plans to correct in the next round of evaluations.

Teacher evaluations will also change because the legislature overhauled the teacher effectiveness rating system last year. Beginning in the 2023-2024 school year, 30% of a teacher’s evaluation will be based on student academic growth, instead of 50%. Teachers who three years in a row have been rated “highly effective” also will face less scrutiny and have more simplified evaluations.

The Gazette’s analysis of the 2021-2022 teacher effectiveness data found only 35 out of 1,401 schools report teachers in the lowest “ineffective” rating. Similarly, only 413 schools report any rated teachers in the second to lowest rating of “partially effective.”

Officials at schools with high rates of ineffective teachers pushed back on the state’s teacher evaluation program’s findings. At Grand Peak Academy, a charter school in El Paso’s School District 49, 96% of the rated teachers are ineffective, the highest percentage of ineffective teachers anywhere in the state, according to the data.

“I can assure you that teachers at GPA are not the least effective teachers in the state of Colorado,” said Nicole Parker, the principal of Grand Peak Academy, in an email. “An article that you should consider writing should be the effectiveness of parents on their child’s violent, disruptive, aggressive, inappropriate behavior that disrupts entire classrooms.”

The Gazette found there are so few schools with high rates of partially effective and ineffective rated teachers that it becomes statistically difficult to draw conclusions on whether school poverty rates and those categories have any correlation.

Nearly 70% of the schools participating in Colorado’s effectiveness rating system report all their teachers as either “highly effective” or “effective,” suggesting that Colorado’s effectiveness ratings may not do a good job of providing accurate and credible information about actual teachers’ instructional performance.

The Gazette found a strong correlation showing the highly effective rated teachers are often in the wealthiest schools.

One 2009 study of teacher evaluation systems across the nation similarly found those systems often fail to distinguish and identify poor performance. That study found that in most school districts less than 1% of teachers were rated as unsatisfactory but 81% of administrators and 57% of teachers could identify a teacher in their school who was ineffective.

Another 2019 analysis by professors at Brown University and Vanderbilt University found other state teacher effectiveness rankings identified far higher rates of poorly performing teachers than Colorado’s system. New Mexico in 2017 identified nearly 30% of assessed teachers as needing improvement while Colorado only identified about 4% as needing improvement that year, that study found.

Two districts, two outcomes

The strong correlation showing the wealthiest schools are far more likely to get the teachers most highly rated is apparent even among school districts bordering each other.

For instance, Pueblo County School District 70, a wealthier district, and Pueblo City School District 60, a poorer district, have striking differences in effectiveness ratings for teachers.

At Pueblo County School District 70, 10 schools have more than 40% of their teachers rated as “highly effective” and none of the schools in the Pueblo City School District 60 have more than 40% of their teachers rated “highly effective.”

“Although the same cannot be said of all school districts, District 60 goes to great lengths to conduct thorough and rigorous evaluations of educators in line with state standards and state educator effectiveness laws,” said Eric DeCesaro, the assistant superintendent of human resources in that district, in a prepared statement. “We train our evaluators to give timely and honest feedback to our educators with the goal of continuous educator improvement each year.

The city district had nine schools registering between 4% to 21% of their rated teachers as “partially effective” while the county district had no schools in that range.

“District 60 has not been immune to the nationwide teacher shortage, particularly at the middle school level,” DeCesaro said. “The Pueblo community is impacted by high levels of poverty among many of our families. As such, our district has its own set of challenges not often found in suburban districts with higher socio-economic conditions.”

luige.delpuerto@coloradopolitics.com