6 months or more: Federal judges in Colorado have trouble moving cases forward | COVER STORY

When Charlotte N. Sweeney took the bench as a federal district judge last summer, she inherited hundreds of pending motions on her first day, some of which had been lingering for years.

“You have to dig out of that or you will never, ever, ever catch up,” she warned at a legal event in July.

Some members of Colorado’s U.S. District Court, however, routinely fail to process their workload in a timely manner. Problematically, one judge’s backlog ranks persistently higher than nearly all of the 1,000-plus trial judges in the federal system.

A high-level status report of each judge’s docket has been in the public domain for roughly three decades. The Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990 requires the federal judiciary, twice a year, to release a report showing the number of motions pending longer than six months for each district judge and magistrate judge.

Yet, multiple lawyers who spoke to Colorado Politics were unaware that judge-specific data existed.

“I am almost always the only one bringing up the CJRA list and educating people that it is out there,” said Jamie Hubbard, a Denver-based attorney who clerked for multiple federal judges, including in Colorado.

“If you’re in front of a judge who generally has zero or a handful of motions on their CJRA list, it shows that is an important metric for them,” she added. “Your motion is likely to be addressed so it doesn’t come on the list. Whereas, you can check in and other judges might have 50 motions on the list.”

Colorado’s trial court has seen rapid turnover in the past two years, with President Joe Biden appointing four new district judges. The district judges, in turn, hired three new full-time magistrate judges, who assist with the workload of the court and sometimes handle civil cases entirely on their own.

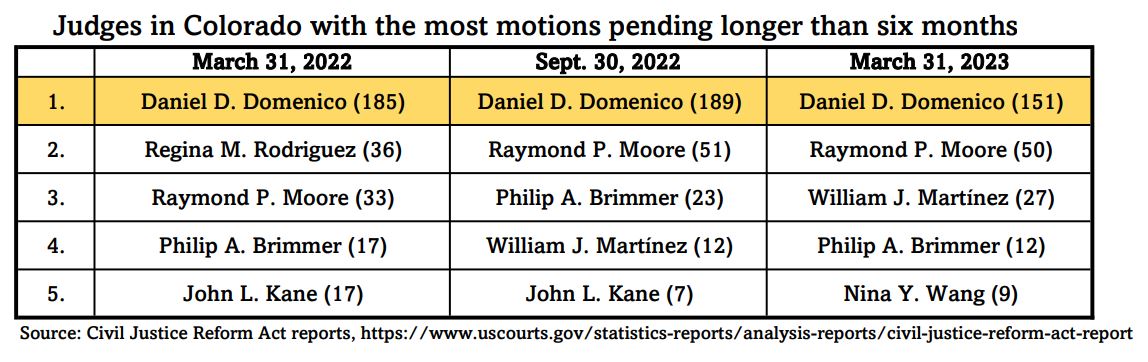

Despite the massive shift in personnel, recent CJRA reports show the same handful of more senior judges chronically leaving motions stacked up on their six-month lists.

Several lawyers who spoke to Colorado Politics believe there is little they can do to prod a judge to act on languishing motions without upsetting them. One attorney, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid retaliation and to be candid, said delays are particularly problematic on motions that could resolve some or all claims in a lawsuit without a trial, known as dispositive motions.

“You’re racking up legal fees and disrupting peoples lives on a claim that the judge will rule cannot move forward,” said the lawyer. “Ideally, you want that dispositive motion dealt with quickly so you and the other side know what’s in front of them.”

The list

In 1988, then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden, representing Delaware, prompted a Brookings Institution taskforce to address the expense and delays in the federal civil justice system. Among the suggestions to enhance accountability and move backlogged cases forward, the taskforce recommended the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts release a public list of each trial judge’s unresolved motions.

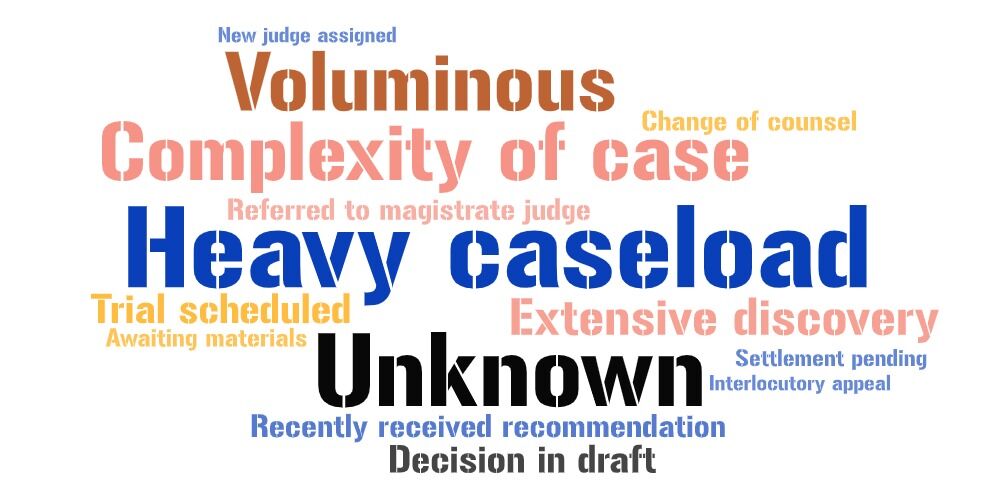

Biden incorporated the provision into the broader Civil Justice Reform Act. Twice a year, the judiciary would issue public reports showing how many motions were pending as of March 31 and Sept. 30 on each district and magistrate judge’s docket. A motion becomes “pending” 30 days after its filing. Judges also have the opportunity to give a reason for the delay, such as “complexity of case,” “extensive discovery involved” or “voluminous” materials.

“The law has had a salutary effect,” The Washington Post wrote in a 1992 editorial. “One Washington lawyer reports, for example, that three cases that had been pending for quite some time in three different district courts were finally resolved the day before the data were due – the implication being that judges across the country were cleaning up old business rather than confessing delay.”

The CJRA does not apply to criminal cases, which have their own legal deadlines. Although the law concerns itself with the promptness of judicial decision making, it does not measure the quality of judges’ orders.

“If given more time for decision, a judge may craft a better reasoned opinion that is less likely to be reversed on appeal and that may provide a helpful precedent for other parties,” wrote law professor R. Lawrence Dessem.

Nonetheless, some judges treat the six-month list seriously. There is also a degree of strategy in culling the list before the cutoff.

“If a motion doesn’t get filed until May, it won’t get on the six-month list until the following March,” said Magistrate Judge N. Reid Neureiter during a legal discussion in August. “Depending on how chambers works, a law clerk might say, ‘Hey I’ve got seven months before the judge will be mad at me for not deciding this.'”

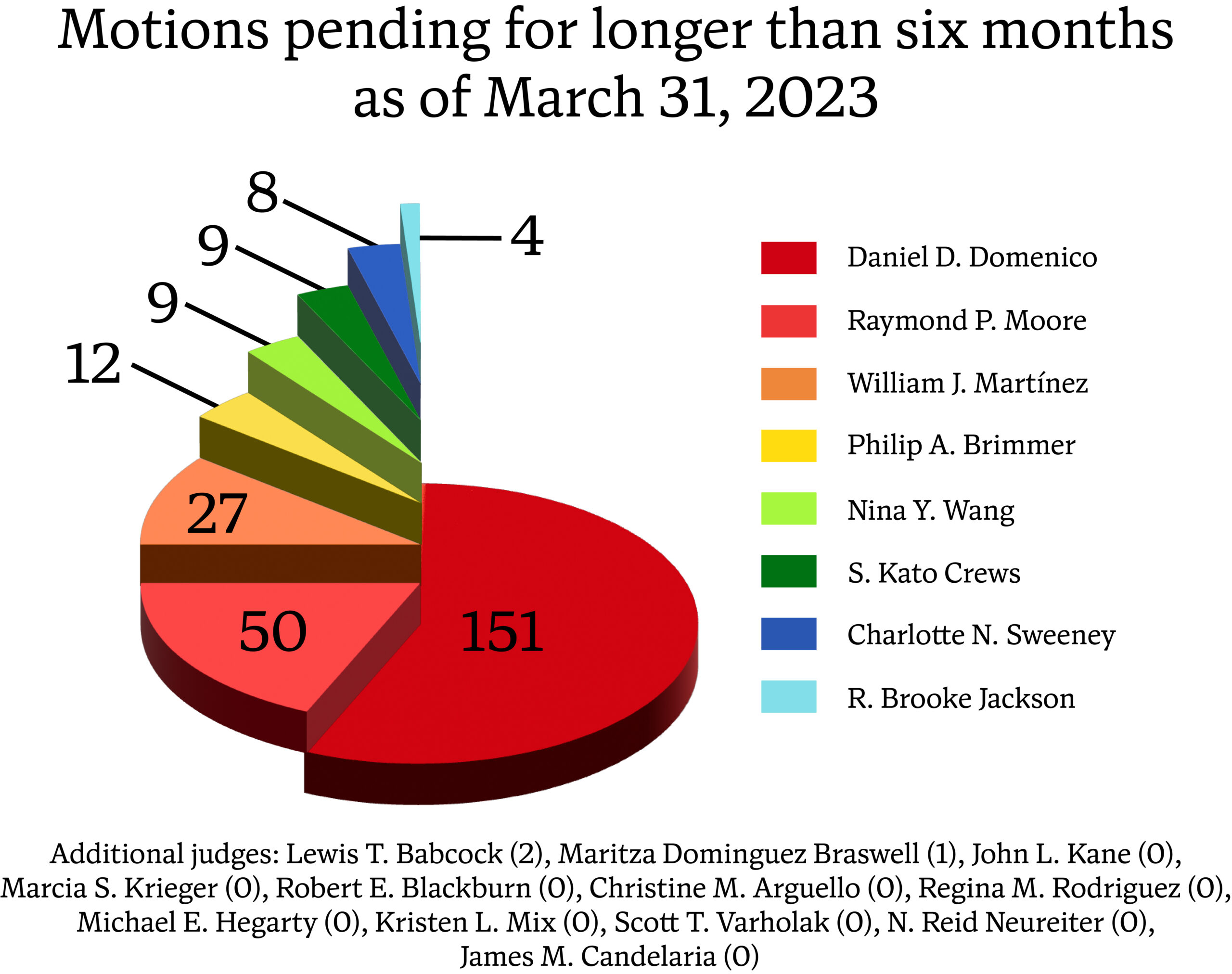

The latest report from March 31, 2023 showed 272 motions pending for longer than six months in Colorado’s district court. The majority of judges faced no overdue motions or a single-digit backlog. A small cohort of district judges reached double digits: Senior Judges William J. Martínez and Raymond P. Moore, both appointees of Barack Obama, and Chief Judge Philip A. Brimmer, picked by George W. Bush.

Judge Daniel D. Domenico had, by far, the most egregious delays: 56% of all overdue motions were his responsibility, encompassing civil rights cases to insurance disputes and medical malpractice.

Since March 2022, Domenico, Moore and Brimmer persistently registered the highest backlog on the court. Colorado Politics invited the judges, through the court’s clerk, to comment or provide context to the data. None chose to do so.

In contrast, the magistrate judges typically had no pending motions at all. Lawyers who spoke to Colorado Politics said it is less common for magistrate judges to handle dispositive motions – meaning motions to dismiss or motions for summary judgment.

But also, magistrate judges, unlike their life-tenured counterparts, must seek reappointment every eight years from the district judges. That provides an incentive to handle a docket efficiently, those familiar with the federal court explained.

“Magistrate judges care because of reappointment, but also because we are dedicated to moving cases as quickly as possible,” said Kristen L. Mix, who retired in August after 16 years as a magistrate judge in Colorado.

The outlier

By his own account, Dan Domenico’s primary interest in 2017 was not in becoming a trial judge.

That year, President Donald Trump nominated Judge Neil M. Gorsuch of Colorado for a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court. His confirmation meant there was a vacancy on the Denver-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. Domenico, a former state solicitor general with conservative credentials, wanted to succeed Gorsuch.

“In January 2017, I met with Senator Gardner’s staff. Given the possibility that Judge Gorsuch’s seat would be opening, I noted my interest was for that position,” he wrote in his U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire, referring to then-U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner.

Domenico reiterated his interest after Gorsuch’s nomination and also spoke with the administration about it. On April 10, Domenico said he attended a reception for Gorsuch’s swearing-in to the Supreme Court. Three days later, Gardner called him to “explain that the White House was planning to recommend” that Trump nominate him to the U.S. District Court instead.

Once he took the bench in 2019, Domenico’s list of motions pending longer than six months steadily began to climb. By September 2021, the backlog crossed into triple digits and ballooned to nearly 200 in 2022.

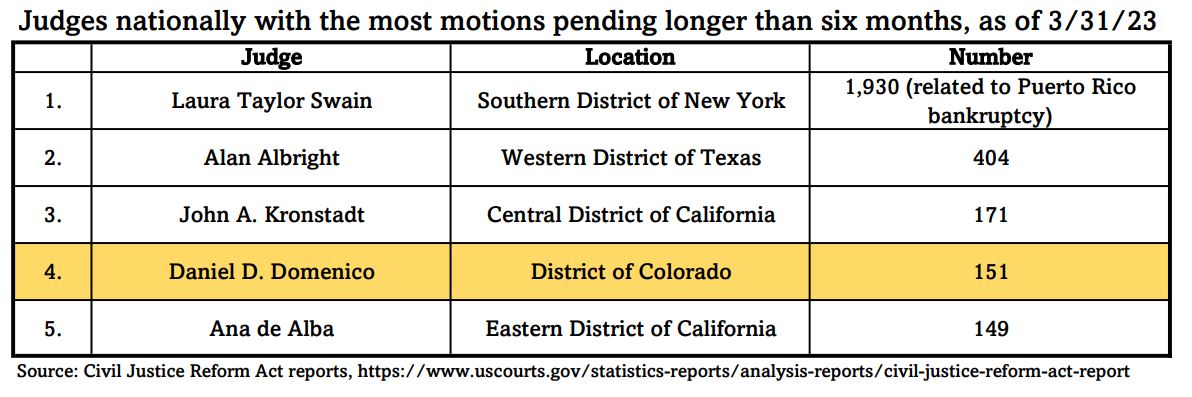

Since then, Domenico has not only been the outlier on Colorado’s trial court, but as of March 31, his backlog was the fourth highest nationwide – out of more than 1,200 district and magistrate judges.

“My personal experience with Judge Domenico has been that when he rules in a case it is a thoughtful and well-reasoned opinion. He is, in my opinion, a very good judge. The problem is, of course, actually getting a timely order,” said an attorney, who lacked client authorization to speak on the record.

As of March 31, Domenico had 151 motions pending longer than six months across more than 60 civil cases. His list also included some of the lengthiest delays of any judge: More than a dozen motions pending longer than two years and a handful that had not been decided after three years.

In one instance, a car wash operator sued the city of Castle Pines. The defendants moved to dismiss in July 2021. Domenico, however, left the motion unaddressed for nearly two years. In April 2023, Judge Gordon P. Gallagher inherited the case after his appointment to the bench. Gallagher ruled on the motion two months later.

In another case filed in 2018, a commercial property owner in Colorado Springs sued its insurer over a damaged roof claim. By the summer of 2020, several motions were past the six-month mark, including a motion for summary judgment. Three years later, according to the electronic docket, Domenico has not ruled on any of those.

In his explanation for nearly all of his overdue motions, Domenico cited his “heavy civil and criminal caseload.”

Jeremy Fogel, a retired district judge from the Northern District of California, said at some point, the chief judge of a court may need to intervene and offer to assist a struggling judge. Fogel also urged backlogged judges not to simply ignore the problem.

“If you don’t tell anybody, you’re kind of isolated and people can easily draw the worst conclusions and think you’re not conscientious or competent or are lazy,” he said. “You don’t want anyone to think that about any judge or court. I think it’s important for people to ask for help.”

Lives on hold

Beginning in 2019, a middle school student in Aspen allegedly became the target of bullying and physical attacks. The student, I.S., reportedly grew too scared to go to school and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. Aspen School District allegedly failed to accommodate his disability, in violation of federal law.

Ten months after I.S. filed his federal complaint, the school district moved to dismiss. Less than two months later, I.S. responded and the school district replied to his response. The motion was then ready for the judge, Raymond Moore, to decide.

Instead, he did nothing.

In May 2023, Gallagher inherited the case from Moore when he took the bench. After asking the parties to explain what the status was, Gallagher quickly denied the motion to dismiss and broke the logjam.

“I’ve had plenty of clients throw in the towel before. Oftentimes, the explanation is, ‘We started this when my son was in this place in his life and now he’s in this place, and I wonder what is the point of this going forward,'” said Igor Raykin, the attorney representing I.S. and his mother. “That is very much a concern.”

Raykin, who brings cases against schools and educational institutions in state and federal court, said his litigation is unlike other civil disputes that are about “moving money from one place to another.” Instead, when children are involved, they may be going without necessary services or support for years on end.

“In our particular case, it’s never quick. And I think I know why. There are not that many education cases that are brought to federal courts,” he said. “If judges don’t see a lot of cases of a particular variety, they’re not going to know the law as well in that field. And it’s going to take them longer to rule.”

In I.S.’s case, Moore did not list a reason for his delay. Behind heavy caseloads and the complexity of a case, a blank or unknown explanation was the third-most-common entry among Colorado’s judges on the six-month list.

Raykin acknowledged that magistrate judges tend to handle motions quicker, but all parties have to agree to let a magistrate judge preside over their civil case. Often, he said, they do not.

One attorney, speaking on condition of anonymity, said there is a bright side to litigating in federal court: Judges there have more resources than their state counterparts and commonly issue more detailed orders.

But, another lawyer pointed out, litigation is inherently stressful and attorneys themselves must balance deadlines imposed by judges across multiple cases.

“It is not an overstatement to say, then, that justice delayed leaves parties feeling disrespected with diminished faith in the legitimacy of the process. We all work under deadlines – and lifetime-appointed federal judges should be no different,” the attorney said.

Blame on both sides of the bench

Not everyone blames the judges for delays in civil cases – including the judges.

“I’ve offered trial dates within two months repeatedly. No one will take them. No one wants a trial that fast,” said Charlotte Sweeney, one of the newer district judges, at a recent legal discussion.

Lawyers bringing civil rights cases called out the defendants – the government – for appealing trial judges’ orders or using other delay tactics.

“I don’t think that we can blame Judge Brimmer for the delays,” said attorney Patricia S. Bangert, who is suing the City and County of Denver and waited two years for Brimmer to resolve its motion to dismiss. “A lot of the time spent litigating this case has been the fault of the city.”

Hubbard, the attorney who clerked for William Martínez after his appointment as a district judge, said that another statistic in the CJRA reports – the number of cases pending longer than three years – is more susceptible to factors outside of the judge’s control. By contrast, judges and clerks actively curate the six-month list.

“We weren’t working 18-hour days up to the deadline to make sure everything was totally zeroed out. But it was an important metric,” she said.

Senior Judge John L. Kane, a Jimmy Carter appointee, argued that recent vacancies on the bench and the increasing complexity of cases have contributed to delays. A rise in prisoner petitions and insurance cases, which can be time consuming, are also key trends, he said.

“What I’ve done as a senior judge is I’ve tried to take these monster cases – highly complex, class actions – that other judges would otherwise have, because it takes so much time,” he explained.

Kane added that lawyers should not be afraid of angering a judge by calling attention to the need to decide a languishing motion.

“I don’t know any judge who gets upset by that. I get a call or a letter that says, ‘This is really important. It’s been under consideration for so long, when can we get a decision?’ I’ll look at it and figure out what the hell’s going on,” he said. “Half the time, it’s because the briefs are so bad.”

In Colorado’s state courts, where judges stand for retention, judges may be called out by citizen-led performance commissions for delays. Extreme gaps in issuing decisions may also be grounds for judicial discipline. Federally, the 10th Circuit’s rules do not generally treat judicial delays as misconduct, unless a judge has an “improper motive” or there is a “habitual delay in a significant number of unrelated cases.”

Fogel, the retired judge from California, said he was very attentive to his six-month motions list because even if he knew he was doing his best, a long list could cause people to doubt his skill as a judge. Ultimately, he did not feel it is appropriate for a judge to blame law clerks for any delay, but there could be underlying problems – declining health or a family issue – causing a judge to fall behind in their workload.

In those circumstances, it is up to the judge and their peers to address unflattering CJRA reports.

“One of the things that judges have a hard time doing is asking for help. They’re embarrassed,” he said. “The best practice for the chief judge would be to go the judge in question and say, ‘I saw this. Obviously, you can’t feel good about it. Is there any way I can help?'”