‘Unexplained or suspicious’ deaths pile up among residents of Colorado’s growing assisted-living industry

Editor’s note: This story is the result of compiling and analyzing nearly five years of occurrence reports submitted to the state by assisted-living facilities, reviewing police records, state Senate committee testimony and court documents. In addition, The Denver Gazette interviewed or received statements from family members of the victims, legal experts, elder care advocates, prosecutors and assisted-living administrators and owners, and advocates for the industry.

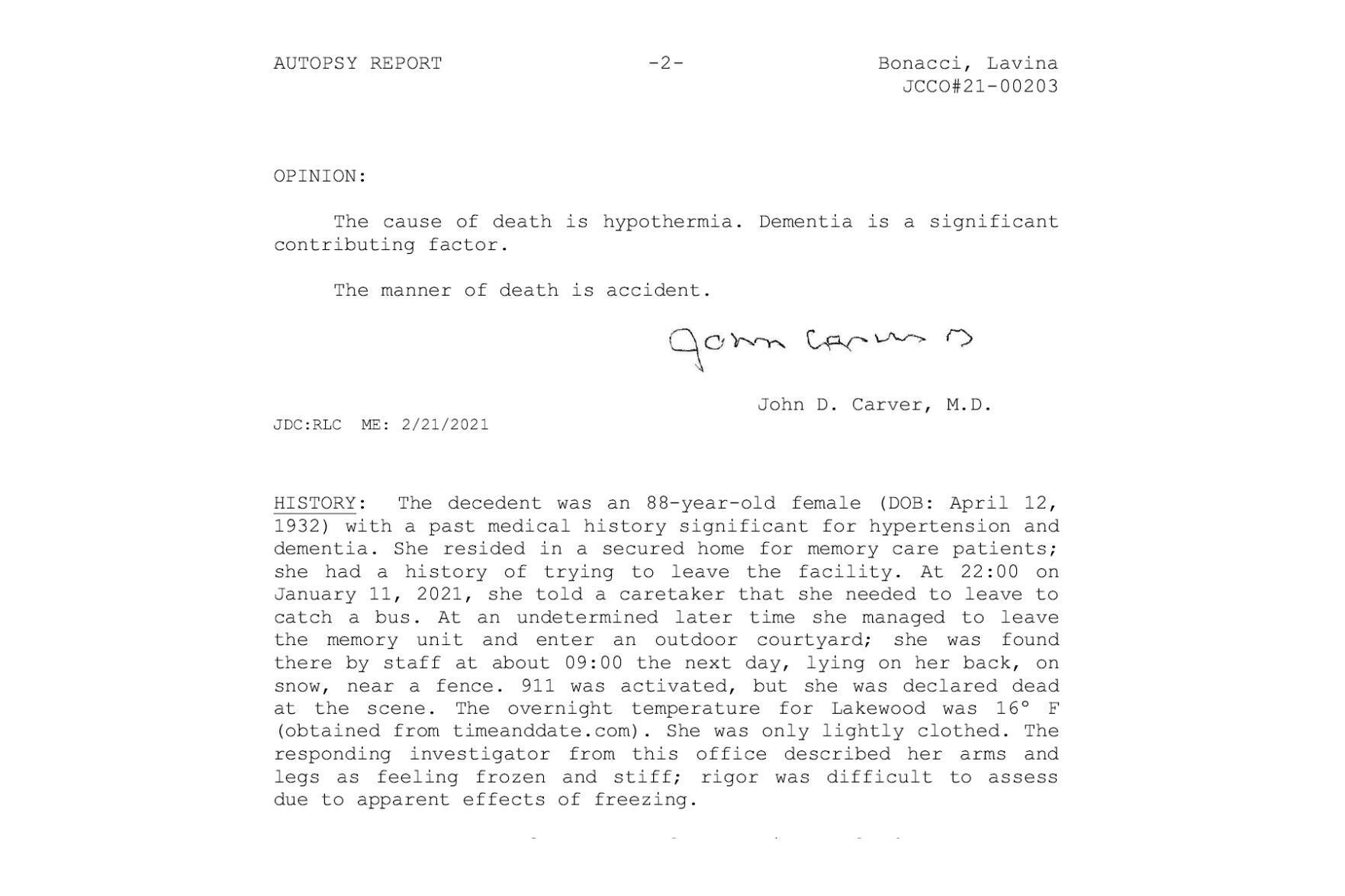

The last time anyone at Applewood Our House assisted-living facility checked on Lavina Bonacci was between 7:30 and 8 p.m. on Jan. 11, 2021. At age 88, her mind had turned foggy with Alzheimer’s disease, and she was known as a wanderer who needed to be regularly monitored to keep her safe.

It is why her family turned to the 16-bed facility in Lakewood the summer before for help.

But on that frigid night, more than 12 hours passed before the staff realized she was missing, eventually finding her outside frozen to death. She was lying on the ground, her legs poking from the bushes in an outdoor area no bigger than a suburban backyard. She was wearing a short-sleeved shirt, thin pants and socks.

Her empty wheelchair was nearby, its tracks visible in the snow. A toothbrush and tube of toothpaste were on the ground next to her, presumably what she grabbed when in her confusion she thought she was leaving.

At least one required nighttime safety check was missed. No one knows how long she had been outside in temperatures that dropped to 16 degrees.

Her body was so frozen, the staff later said, ice had formed inside her mouth. The autopsy report said she died of hypothermia. It was ruled an accident.

Gruesome deaths like hers are often seen as terrible but isolated mistakes. But a four-month Denver Gazette investigation into Colorado’s burgeoning assisted-living industry revealed that preventable deaths at facilities promising a watchful eye happened more often than the public knows.

There were 110 documented deaths classified by the state as “unexplained or suspicious” at assisted-living facilities between Jan. 1, 2018, and Oct. 28, 2022, according to Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment records obtained and analyzed by The Gazette. The records come from mandatory self-reporting by facilities.

But the Gazette analysis of the more than 4,500 reports plus independent reporting also discovered three dozen more deaths or incidents of neglect and abuse that later led to death. In some of those cases, the deaths were found within state records classified as something other than death. In at least one other, a facility never reported a death at all.

The Gazette further found that after a tragedy, punishment to those in charge is minimal due to vague state regulations, limited or nonexistent criminal prosecution and a fine structure currently so low a national expert called it “absurd.”

The series of preventable deaths across the state included a resident who died after not getting medication for days, another with an untreated wound that led to fatal sepsis, and a yet another left unattended outside for six hours in 100-degree heat that slowly baked her to death.

Bonacci coroner reportJimTrotterEditor

jim.trotter@gazette.com

https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/7be07d6cb25fd98cd2bd0b13bbf16452?s=100&d=mm&r=g

There have been at least six cases of hypothermia alone – four fatal, including Lavina Bonacci’s. In each, an elderly resident with signs of dementia walked out of a supposedly secure facility into the Colorado cold and was not found for hours:

? Dec. 8, 2019. Spring Ridge Park in Wheat Ridge. A memory care resident in her 90s wandered outside into the fenced courtyard sometime after 5:45 p.m. No one spotted her on the facility’s surveillance camera until 9 p.m., lying on the concrete. Records were falsified by a staff member, who was later fired, to make it appear she had been checked at 6 p.m. The resident, whose name was not released, was taken to the hospital with hypothermia.

? Feb. 3, 2020. Union Printers Home in Colorado Springs. Margarita Sams, 89, was found frozen to death on an outside bench just 40 yards from the facility. Her mental condition had deteriorated, and staff were told to keep a close watch on her. A surveillance video showed her heading for an exterior door around 4 a.m. A thorough search was not conducted for seven more hours.

The facility was shut down by the state and three workers initially faced criminal charges but those were later dropped. (While Sams was a nursing home resident, her death was included in this story because the facility also had assisted living.)

? Oct. 8, 2020. Mary Sandoe House in Boulder. A resident in her 90s with dementia went missing sometime after 10:45 p.m. She was found lying on the ground at 7 a.m. the next day. Around 3 a.m. a staff member noticed she was not in her room and texted another worker. That staff member later admitted she was half-asleep and confused the missing resident with another who was often in the hospital. No search was conducted. After discovered, the resident, whose name was not released, was taken to the hospital and died three days later of pneumonia. The facility voluntarily closed last year.

? Jan. 2, 2021. Morningstar Bear Creek in Colorado Springs. A resident in her 70s with dementia was found outside at night in the courtyard wearing her nightclothes. Staff said they did not know how long she had been outside, despite a requirement that residents be checked every two hours and the courtyard searched to make sure no one was outside. The resident, whose name was not released, was taken to the hospital with a fractured arm and signs of hypothermia. Two staff members were fired. The resident returned to the facility after being released from the hospital.

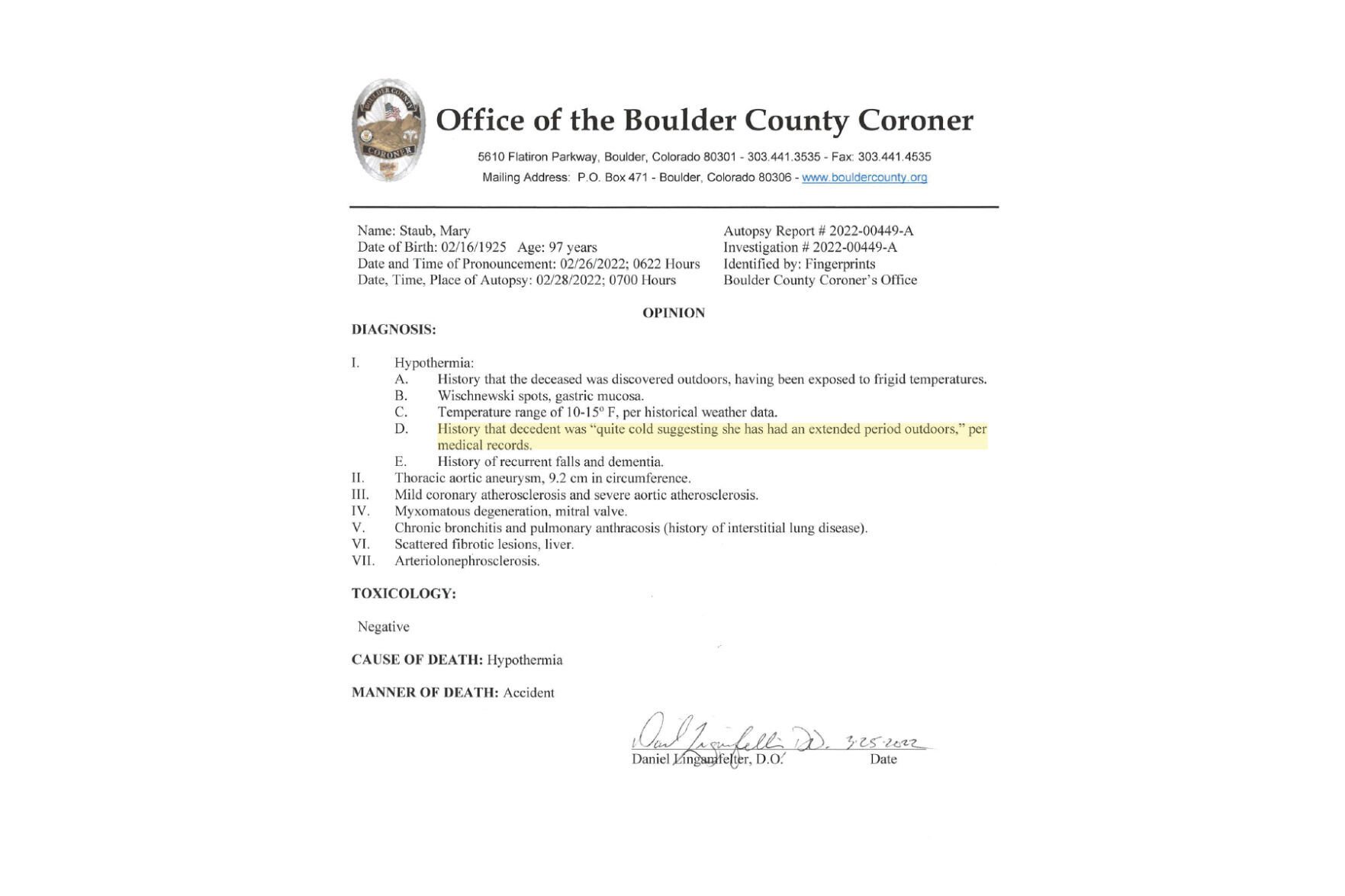

? Feb. 26, 2022. Balfour at Lavender Farms in Louisville. Mary Jo Staub, 97, was found frozen to death after being trapped outside for more than five hours in temperatures between 10 and 15 degrees. The facility’s surveillance camera showed that just after midnight, she wandered outside unnoticed and became locked out. Her family said they were told she would be checked at night.

The footage, according to a lawsuit filed by the family, showed her trying to scoot with her walker before falling in the snow and crawling the rest of the way on her hands and knees to a glass door, leaving a trail of blood. She pounded on it with her fists and a broom in view of a nursing station that was unoccupied. At 1:40 a.m. she collapsed on the sidewalk, her body twitching for two more hours before it stopped moving at 4:23 a.m. She was found just before 6 a.m. The cause of death was hypothermia. It was ruled an accident.

Assisted living facility officials insist resident safety is their priority.

“I am still so devastated,” said Sherrie Bonham, the administrator at Applewood Our House where Bonacci died. She said she immediately reported the death to the state and police as required and filed a correction plan.

She said she was told she could not legally lock the door to keep residents inside. She has since installed an alarm on the door.

A spokesperson for MorningStar said in an email the facility took the incident there “extremely seriously,” launching an investigation, working with the state, and taking corrective action “to ensure residents are protected in our community.”

Spring Ridge Park and Balfour did not respond to multiple emailed requests for comment. The other facilities are closed.

Advocates for the elderly say that most of the time the assisted-living model works, filling an important role in the health care continuum when people can no longer live independently. It is especially welcomed by families overwhelmed by the needs of a parent or grandparent in cognitive decline.

But they also say the lack of substantial penalties in Colorado when things go wrong points to a systemic failure to protect its most vulnerable seniors. The stakes are especially high in a state with the nation’s third-fastest population growth rate of people ages 65 to 84, increasing by more than 300,000 in the past decade and projected to grow by another 265,000 in the next, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

“We can no longer excuse these deaths as accidents. They are homicidal negligence,” said Shannon Gimbel, ombudsman manager at the area agency on aging for the Denver Regional Council of Governments. “Until there is a real consequence – or the fear of a consequence – nothing is going to change.”

A $96 billion market

Since its inception in the 1980s, families have been drawn to assisted living’s promise of safe, steady care mixed with hominess, finding it preferable to the perceived dreariness of nursing homes.

There are currently 665 assisted-living facilities licensed in Colorado, although many are small. That is up from 562 a decade ago and now outnumbering licensed nursing homes by nearly 3 to 1, according to state data.

Nationally, assisted living has become a $96 billion market with projections to reach $141 billion by the end of the decade.

In Colorado, the cost of assisted living is now roughly $5,000-$7,000 per month plus added services. At some facilities, it is more than $10,000. The bulk is not covered by traditional health insurance or Medicare. And Medicaid is only accepted in limited circumstances.

Yet despite the explosive growth, assisted living, unlike nursing homes, has no direct federal oversight. Regulation is left to individual states. In Colorado, administrators do not have to be licensed as they are in nursing homes. And the qualifications for assisted-living staff – often paid little more than minimum wage – are also less stringent than those in nursing homes, because it is assumed residents do not need as much hands-on attention.

In recent years, though, the original model has evolved to offer higher levels of care, especially for those in memory units. Critics say that Colorado’s regulations have not kept pace with the change, setting the stage for problems.

And when tragedy occurs, accountability can be elusive.

Criminal prosecutions are rare. Although police investigate – some departments now have elder abuse specialists – it often stops there. Cases are not forwarded to the attorney general or district attorney, because officers conclude there is not enough evidence of a crime or don’t know who is culpable. Even if forwarded, prosecutors may decide the case is not strong enough to pursue.

“We will review any case of abuse or neglect resulting in death that is presented to our office by any law enforcement agency,” said Eric Ross, media spokesperson for the 18th Judicial District which includes Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert and Lincoln counties. But he added, “to win a conviction, prosecutors must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. If there is no likelihood of a conviction or a case lacks sufficient evidence for us to take to trial, we must dismiss the case.”

Lawrence Pacheco, a spokesperson for the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, said that charges will only be filed by that office if “the elements of a chargeable crime have been established,” and if investigators can “identify the person who committed the offense.”

So, enforcement falls to the limited muscle of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. While the regulatory agency could suspend a facility’s license, that, too, is uncommon. It has happened just five times since 2019.

The state can take the intermediary step of issuing a “conditional” license, which means the facility requires a higher level of monitoring and stricter rules as a warning to bring the facility into compliance. CDPHE has issued 31 conditional licenses since 2019 – sometimes more than once to the same facility, it said.

More typically, though, violations – including those that led to a death – are met with citations and fines along with a demand to fix deficiencies.

Under current state law, the maximum fine is $2,000 per year per facility, no matter the number of violations. It equates to roughly one resident’s weekly rent at some facilities.

“That’s absurd,” said Sam Brooks, director of public policy at Washington D.C.-based Consumer Voice, a national advocacy group for residents in long-term care and their families. “Why would you comply with anything?”

Fines increasing

The Gazette’s investigation found that fines against facilities are sometimes even less.

Balfour at Lavender Farms, where Mary Jo Staub froze to death, received eight citations and was fined $1,500, according to CDPHE. Applewood Our House, where Lavina Bonacci froze to death, received one citation and no fine at all.

No criminal charges were filed in either case.

“The message we got was the state does not really consider events like our mother’s death a big deal,” Mary Beth Bonacci said in testimony last year before a heated state Senate committee to revamp regulations.

Bonacci declined an interview by The Gazette because of a nondisclosure agreement that is part of her family’s out-of-court settlement with the facility.

“We recognize there are sometimes tragic outcomes at health facilities, and we are committed to doing all we can to protect vulnerable residents. It is our mission,” Elaine McManis, director of the health facilities and emergency medical services at CDPHE, said in an emailed statement. “One of our main strategies to protect residents is to assist facilities to correct issues quickly once we identify problems.”

Mary Staub autopsyJimTrotterEditor

jim.trotter@gazette.com

https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/7be07d6cb25fd98cd2bd0b13bbf16452?s=100&d=mm&r=g

The agency added that when determining the fine, a facility’s past and current record of compliance is taken into consideration.

Last year, state Sen. Jessie Danielson, D-Jefferson County, introduced Senate Bill 154, which removed all limits on fines. The proposal was met with swift and strong opposition from the assisted-living industry, contending it was too punitive and could potentially drive small homes out of business or have the unintended consequence of creating financial hardship that could reduce services to residents.

A compromise was struck, and the bill passed into law with the fine for the most serious infractions set at $10,000 per incident with the possibility of even more if the violation is egregious. Set to go into effect next year, the details of the new law are still being reviewed before final rules are approved.

The current version of the rules state that violations resulting in serious injury or death will come with a range of fine from $2,000 to $10,000 with the possibility of more.

While acknowledging that $2,000 “was not much,” Deborah Lively, director of public policy and public affairs for LeadingAge Colorado, the largest association of senior living care providers in the state, said the higher fines are ill-advised.

“There’s no real research out there that increased fines improves quality of care,” she said.

‘Unexplained or suspicious’

Assisted-living facilities are required to report problems or complaints to the state, known as an “occurrence,” to “capture serious issues that must be reported to us quickly,” CDPHE said in its emailed statement. Occurrences are classified under categories such as death, neglect, physical, verbal or sexual abuse, misappropriation of property and drug diversion, which includes medication errors or a drug gone missing.

To be counted as a death by CDPHE, the loss of life must be “reportable to the coroner as unexplained or suspicious,” according to the agency’s manual. CDPHE further explained to The Gazette that “deaths that are reportable to coroners may have resulted from actions from facility staff.”

The state’s reporting manual also recommends that if an occurrence starts as one type of incident but escalates, a facility should report it as the more serious.

Under the current system, an occurrence can only be logged under one category, and facilities determine the category when submitting to the state. The submission is later reviewed by CDPHE to ensure it “best fits the details of the situation,” the agency said.

There were 110 state-classified deaths between Jan. 1, 2018, and Oct. 28, 2022, The Gazette’s analysis found.

It is difficult to put that into national perspective because there is no uniform tracking and each state has its own system, creating a patchwork of rules and accountability.

Even within Colorado there are inconsistencies. The Gazette investigation, for instance, found an additional three dozen deaths not classified as deaths and listed in other categories. Most were caused by accidents, such as falls, or the resident later died at a hospital or in hospice after an incident. Other omissions, though, revealed horrific cases that raise questions as to why the death was not counted as a death.

For instance, Hazel Place died in June 2021 after being trapped outside unnoticed for six hours in temperatures topping 100 degrees. Staff at Cappella of Grand Junction’s memory unit falsified records to make it appear the 86-year-old was checked and given medication when she had not. She was only discovered after the husband of another resident saw her through a hallway window slumped on a patio love seat.

Three workers were charged by the Attorney General’s Office in connection with the death. One was acquitted after trial, and the other two pleaded guilty, serving 17 and 33 days in Mesa County jail, respectively.

CDPHE classified the case as neglect.

Hazel Place’s death and its aftermath were the subject of a Jan. 19 Gazette investigation.

A May 2018 death of a resident at Retreat at Sunny Vista in Colorado Springs also was not classified as a death. The elderly resident, whose name was not disclosed, died after not getting his medication for days, including missing overnight oxygen for nine days.

The January 2021 death at Pine Grove Crossing in Parker also was not classified as a death. There, an elderly woman was force-fed by a staff member until she began to violently vomit, according to the CDPHE report. The resident, who was not identified, was found dead the next morning in her bed, believed to have aspirated her vomit. The death was not reported to the state as required at the time and only discovered after the facility changed owners.

The Sunny Vista death was classified as neglect and the Pine Grove death was classified as physical abuse. No on-site inspection was conducted by CDPHE in either case, the agency said, nor were any fines issued.

Cappella Living Solutions, which provides management services for Sunny Vista, said in an emailed statement it “self-reported potential concerns, cooperated with external evaluations, and conducted an internal review, resulting in appropriate action being taken.”

Christian Living Solutions, which owns Capella of Grand Junction, previously told The Gazette it self-reported the circumstances surrounding Hazel Place’s death and cooperated with authorities.

Pine Grove Crossing did not respond to emails requesting comment.

Two deaths

Melisa Goodard was warned by a hospice worker to steel herself before seeing her mother’s bashed and bloodied face. Yet when she walked into her mother’s room at Almost Like Home assisted-living facility in Arvada, she felt sick. “I almost threw up.”

It was Nov. 25, 2020. Goodard was told her 76-year-old mother, Judith McCurry, nonverbal and mostly immobile from frontal-lobe aphasia, had somehow rolled off a 2-foot-high bed onto a mat and struck her face. It didn’t make sense. How could there be that much damage?

McCurry had been taken to the hospital but released. By the next day, though, her wounds looked significantly worse, possibly because she was taking blood thinners which can exacerbate bruising. She returned to the hospital. A nurse called the police to report possible abuse or neglect, but the investigation stalled.

A doctor told the family it was probably the beginning of the end. Less than four months later, in March 2021, McCurry was dead. She never fully recovered even after being moved to a new facility where Goodard said the care was excellent. Her mother had lost six teeth from the fall that made it difficult to eat. Her death certificate said she died from malnutrition.

WARNING: Graphic photo

Six weeks before Judith McCurry’s fall, Sylvia Torralba visited her 78-year-old mother at Almost Like Home. She was stunned at how much her condition had deteriorated during the months she had been unable to come because of COVID. Julia Ann Gutierrez had lost nearly 40 pounds, was pale, and nearly unresponsive. She kept shifting in her wheelchair as if she was uncomfortable, but because she had dementia, she couldn’t express what was wrong. A worker said there was a “really bad” sore on her buttocks.

Torralba asked why her mother had not been treated. The administrator later told CDPHE a clinic was called the day before. The clinic told investigators it never received the call. Torralba called the doctor herself who dispatched a mobile medical unit. Gutierrez was taken to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with dehydration so severe it caused irreversible bowel damage. She also had an open wound, a serious urinary tract infection that spread through her body, and her blood pressure was dangerously low. The doctor told the family there was nothing much that could be done.

Gutierrez died Oct. 13 at her daughter’s home.

The details of the two deaths were pieced together from local news, first reported by CBS-Colorado, state Senate testimony, police records and the CDPHE investigations. Both daughters declined to be interviewed by The Gazette about their mother’s deaths because they, too, are under nondisclosure agreements that do not allow them to disparage the facility or even name it.

Arvada police investigated the two cases but concluded there were no crimes. CDPHE classified the deaths as neglect. Almost Like Home received 31 citations that year and fines that totaled the maximum of $2,000. The state took the further step of putting a condition on the facility’s license, requiring it be monitored by an outside management company.

In September 2021, Assured Senior Living, which now operates a total of 16 long-term care facilities in Colorado, took over management of Almost Like Home and finalized the purchase last year.

At the April 2022 state Senate hearing for SB 154, Goodard introduced herself to Francis LeGasse Jr., the owner of Assured Senior Living. “He made me a ton of promises,” she said, “He said this would not happen again.”

Debbie Ladley knew none of what had come before when her 78-year-old mother, Beverly Montgomery moved in during the fall of 2021 during the management transition. But almost immediately she saw troubling signs that never got better.

On Thanksgiving 2021, Ladley remembers the terrible smell when her mother got in the car. Her adult diaper was so saturated with urine it could not be explained as a recent accident. Over the coming months, there were several trips to the hospital for urinary tract infections. “She never had UTIs before,” Ladley said. “My mom was not being taken care of.”

Ladley got a call on Jan. 7, 2023, from her stepfather that her mother was in pain and would not get out of bed. But because of her dementia she could not explain why. Montgomery was taken to the hospital where an X-ray showed three broken ribs. There were also bruises on her legs, arms and forehead, some old. Ladley said the facility staff had no explanation and acted surprised.

After being released from the hospital, Montgomery returned to the assisted-living facility on Jan. 11. The next day, she was found on the floor, presumably after falling out of bed unnoticed. This time the X-ray showed a broken hip. She died at a hospice facility on Jan. 19.

CDPHE was unaware of the death until The Gazette told the agency in June.

In response to The Gazette’s questions, LeGasse, the owner, did not address why the incident was not reported to CDPHE. “It is our policy to not speak about residents, their families, or anyone in our care in the public setting,” the email said.

On May 18, CDPHE sent a letter to LeGasse warning him the facility was under a “fitness review” that put its license renewal in jeopardy. For more than a decade there have been repeated violations and it failed to take proper action, the letter said.

CDPHE letter

The facility’s “inability to sustain implementation” of past corrective measures “rises to the level of a pattern of behavior or history of noncompliance” that could endanger residents, the agency warned.

In response, LeGasse wrote to the agency on May 31 stating the “colossus failures” at Almost Like Home predated his company and that the quality and care has improved since. He added that the Arvada location is scheduled to become a traumatic brain injury residential facility and his company is not seeking to renew the assisted-living license there.

CDPHE response Final – signed.pdf

“We have removed the ‘black eye’ this location caused for CDPHE, the community and the state,” he said in his letter.

Gimbel, the ombudsman, acknowledged CDPHE has been more aggressive of late. But she also said that facilities still “get a ton of chances.”

She sees a larger issue in the way society cares for its old and sick.

“Imagine if these things happened in day care,” she said. “It would not be the same.”

Balfour lawsuitAssured response

Staub lawsuit