Arapahoe County judge let biased juror serve, prompting reversal of serial rapist’s convictions

A man with a history of raping women, who is serving 136 years in prison, will receive a new trial after the state’s second-highest court concluded an Arapahoe County judge allowed a biased juror to serve in the 2021 trial.

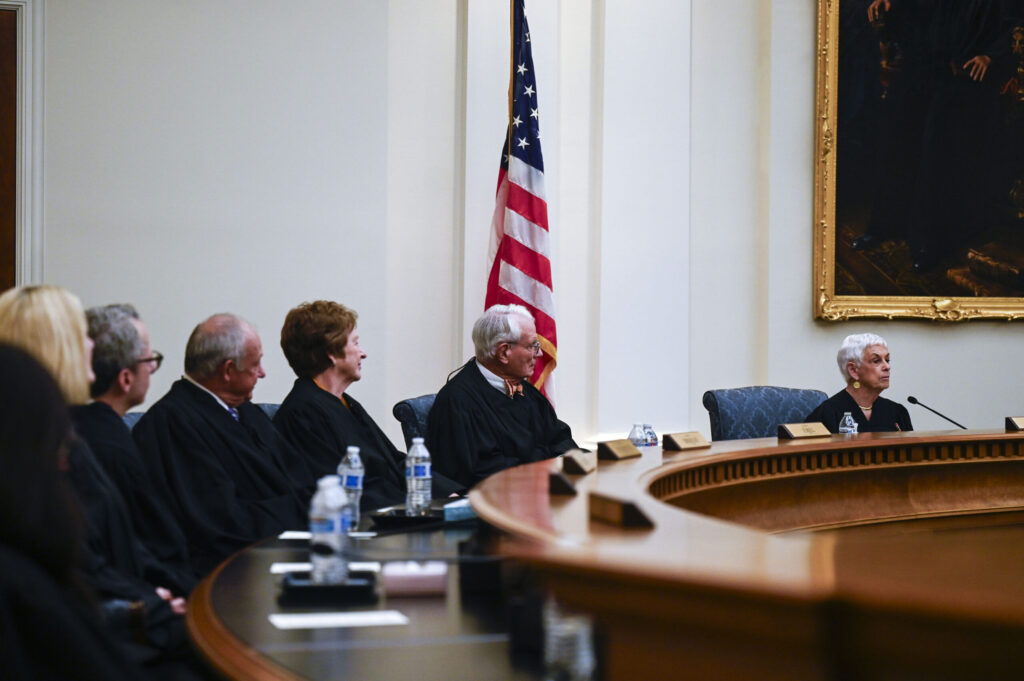

On Thursday, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals concluded, by 2-1, that it was improper for a woman to remain on Tre Miekale Carrasco’s jury after she admitted it would be “hard” to find him not guilty. District Court Judge Ben L. Leutwyler’s refusal to dismiss the woman, identified as Juror H, was a mistake.

“Juror H adhered to an incorrect view of the law,” wrote Judge Anthony J. Navarro in the June 15 opinion. “Her statements indicated plainly that she would have difficulty presuming Carrasco innocent of the charged crimes.”

Judge David H. Yun believed a new trial for Carrasco was unwarranted. He honed in on a specific moment between Juror H’s statements and Leutwyler’s decision not to dismiss her. Leutwyler asked all jurors to raise their hands if they could not presume Carrasco was innocent until proven guilty. Nobody, including Juror H, raised their hand.

“By not raising her hand, Juror H affirmed that she could apply the presumption of innocence. No other reasonable conclusion, in my view, could be reached,” Yun argued. “At some point, we have to trust that what a juror indicated is what she meant. And this is something that the trial court, not an appellate court, should decide.”

Case: People v. Carrasco

Decided: June 15, 2023

Jurisdiction: Arapahoe County

Ruling: 2-1

Judges: Anthony J. Navarro (author)

Jaclyn Casey Brown

David H. Yun (dissent)

Background: Serial rapist sentenced to 136 years in prison in Arapahoe County

Carrasco had a history of voyeurism and sexual assault that began in 2008 in Kansas and continued into Colorado. In February 2019, Carrasco carjacked a woman, then later drove to a Cherry Hills Village home and raped another woman. Prosecutors charged him with aggravated motor vehicle theft, sexual assault, kidnapping and other offenses.

An Arapahoe County jury convicted him in 2021 and Leutwyler sentenced Carrasco to 136 years in prison. Last year, a Kansas judge sentenced Carrasco to 96 years for another rape days before his Colorado spree.

During jury selection, Carrasco’s attorney asked whether anyone believed Carrasco was more likely to be guilty because there were “two separate sets of allegations,” referring to the carjacking and the sexual assault.

Juror H said she had thought to herself, “He’s been busy,” when she heard about the charges.

“It sounds like it’s hard for you to come from a place where he’s a hundred percent innocent before you’ve even seen the evidence,” the defense attorney observed.

“That’s fair,” replied Juror H.

Later in jury selection, she reaffirmed that she was not “starting from zero” because of the dual sets of charges, and “that’s going to be in the back of my mind.”

Leutwyler then told all jurors to remember the government needed to prove Carrasco guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

“Please raise your hand if you cannot give Mr. Carrasco, for any reason, the presumption of innocence,” he said, observing “there are no hands.”

The defense moved to dismiss, or “strike,” several jurors for bias. Among those was Juror H, who, Carrasco’s lawyer said, indicated it “would be difficult for her to give him that presumption of innocence.”

Leutwyler declined to strike Juror H, calling it “speculative” that anyone would believe Carrasco was guilty solely because he was charged with two sets of crimes. He added that he invited the jurors to signal if they could not follow the law, “and I got no responses.”

Defendants have a constitutional right to an impartial jury, but it is possible for a juror who initially misunderstands the law to serve if they are “rehabilitated.” Rehabilitation entails additional questioning that secures a juror’s commitment to set aside their bias.

On appeal, Carrasco argued Juror H was never rehabilitated from her initial bias, while the government claimed she was.

Navarro, writing for himself and Judge Jaclyn Casey Brown, acknowledged Leutwyler’s explanation about the presumption of innocence could have corrected Juror H’s preconceived opinion. However, under the circumstances, it was unclear whether Leutwyler’s directive to “raise your hand” was effective.

Carrasco’s jurors “were not highly responsive to group questioning. On several occasions where the parties and the court asked questions,” wrote Navarro, “the jurors did not volunteer answers.”

While Juror H’s non-response could indicate she understood Leutwyler’s description of the law, it could have also signaled her “reluctance to disagree with the court,” Navarro added.

Because Juror H was biased and she was permitted to serve, the panel’s majority ordered a new trial for Carrasco.

Yun, in dissent, maintained it was improper for the appellate court to second-guess Leutwyler’s assessment of Juror H’s impartiality based solely on an after-the-fact transcript.

Leutwyler “was in a superior position to evaluate Juror H’s state of mind,” Yun wrote.

The case is People v. Carrasco.