Colorado Supreme Court shuts door on man’s challenge to private riverbed ownership

Private ownership of river and stream beds in Colorado will continue unchallenged for now, as the state Supreme Court on Monday ruled that a man lacks standing to declare Colorado – and, by extension, the public – the rightful owner of his preferred fishing spot.

For several years, Roger Hill has contested the ability of Mark Warsewa and Linda Joseph to exclude him from a segment of the Arkansas River that Warsewa and Joseph own. Hill, who was chased away while trying to fish from the riverbed, argued he could not be trespassing because Colorado has actually owned the submerged land in question for nearly 150 years.

Although a lower court gave Hill the green light to proceed, the Supreme Court declined to wade into the ownership question. For Hill to even get into court, he needed to show an injury to his own legally protected interest. But in this case, wrote Justice Melissa Hart, Colorado was the party whose interest was at stake – and the state had no desire to declare itself the riverbed owner.

“Proof of the state’s ownership of the riverbed is a necessary prerequisite to his claimed right to fish in that portion of the Arkansas River,” Hart wrote in the June 5 opinion. “There is no way to adjudicate whether Warsewa and Joseph do not own the riverbed without considering who does.“

The case attracted the attention of multiple outside organizations who worried the decision would upset private property rights statewide and encourage trespassing, or, alternatively, would ensure certain waterways rightfully remain accessible for the public to enjoy in a state famous for its outdoor recreation.

In arguing for a change to the status quo, 12 law professors pointed out Colorado is the only western state that has not acknowledged whether any of its waterways were navigable at statehood and, therefore, open to public access. Elsewhere, court cases have affirmed states’ duty to hold such waterways “in trust” for the public, which the other branches of government have then implemented.

Mark Squillace, a lawyer for Hill, said he was disappointed the Supreme Court cut off an avenue for greater public access to waterways.

“These are rights that are enjoyed by the citizens of every other state in the country and it is, frankly, shocking that here in Colorado, a state renowned for its outdoor recreational opportunities, our Supreme Court would deny a member of the public the right to even raise the issue,” he said.

Warsewa and Joseph’s ownership of the riverbed segment in question stemmed from a federal land patent, which the government granted for waterways deemed non-navigable at Colorado’s statehood in 1876. Hill, in attempting to fish from the riverbed, allegedly endured threats of arrest and physical intimidation from the landowners.

A Fremont County judge originally dismissed his lawsuit to declare the state, and not Warsewa and Joseph, the owner in trust of the riverbed. Last year, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals reinstated Hill’s lawsuit in part. Because Hill credibly alleged the landowners took action against him for trespassing, he could challenge his exclusion, the panel ruled.

But rather than embrace its potential ownership of the Arkansas River segment, Colorado urged the Supreme Court to throw out Hill’s lawsuit.

“The state has never asserted that it owns any rivers in Colorado because they were navigable at statehood, and Mr. Hill can’t assert any interest on the state’s behalf,” former Solicitor General Eric R. Olson told the justices in May.

During the appeal, the Supreme Court heard various groups caution a decision in Hill’s favor would encourage outdoor recreation enthusiasts to trespass and be threatened with prosecution, thus giving them standing to challenge riverbed ownership. Successful lawsuits could, in turn, take land from private owners and turn it over to the state for public use.

Trade groups for anglers, hunters and river outfitters countered that other states have addressed ownership of their own waterways, yet Colorado remains the outlier that has not.

The approach “fails to recognize the diversity of passionate river users in Colorado and threatens to deprive those users of access to the courts when their interests are threatened,” wrote attorneys for the associations.

Ultimately, whether Colorado or Warsewa and Joseph own the contested riverbed is not a question Hill can ask the judiciary to resolve, the Supreme Court decided.

Wyatt Sassman, an assistant professor at the University of Denver who advocated for the Supreme Court to let the lawsuit proceed, lamented the lack of a clear answer about who has a right to the Arkansas River riverbed.

“This decision should prompt the state to determine the navigable rivers in Colorado and take seriously its responsibilities to Mr. Hill and the public,” he said.

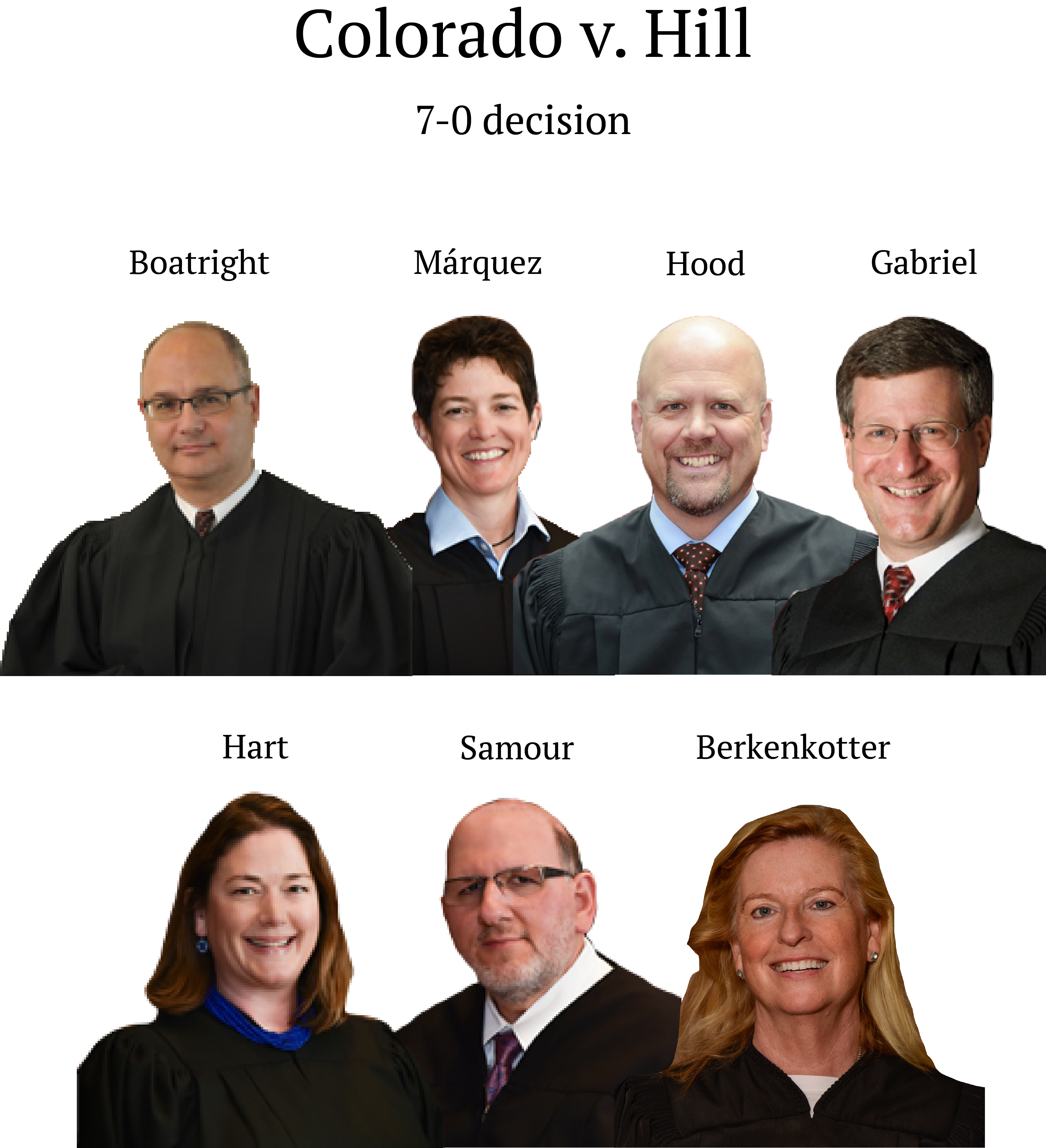

The case is State of Colorado v. Hill.