‘The law is the law’: Conifer students experience real appellate cases, quiz judges

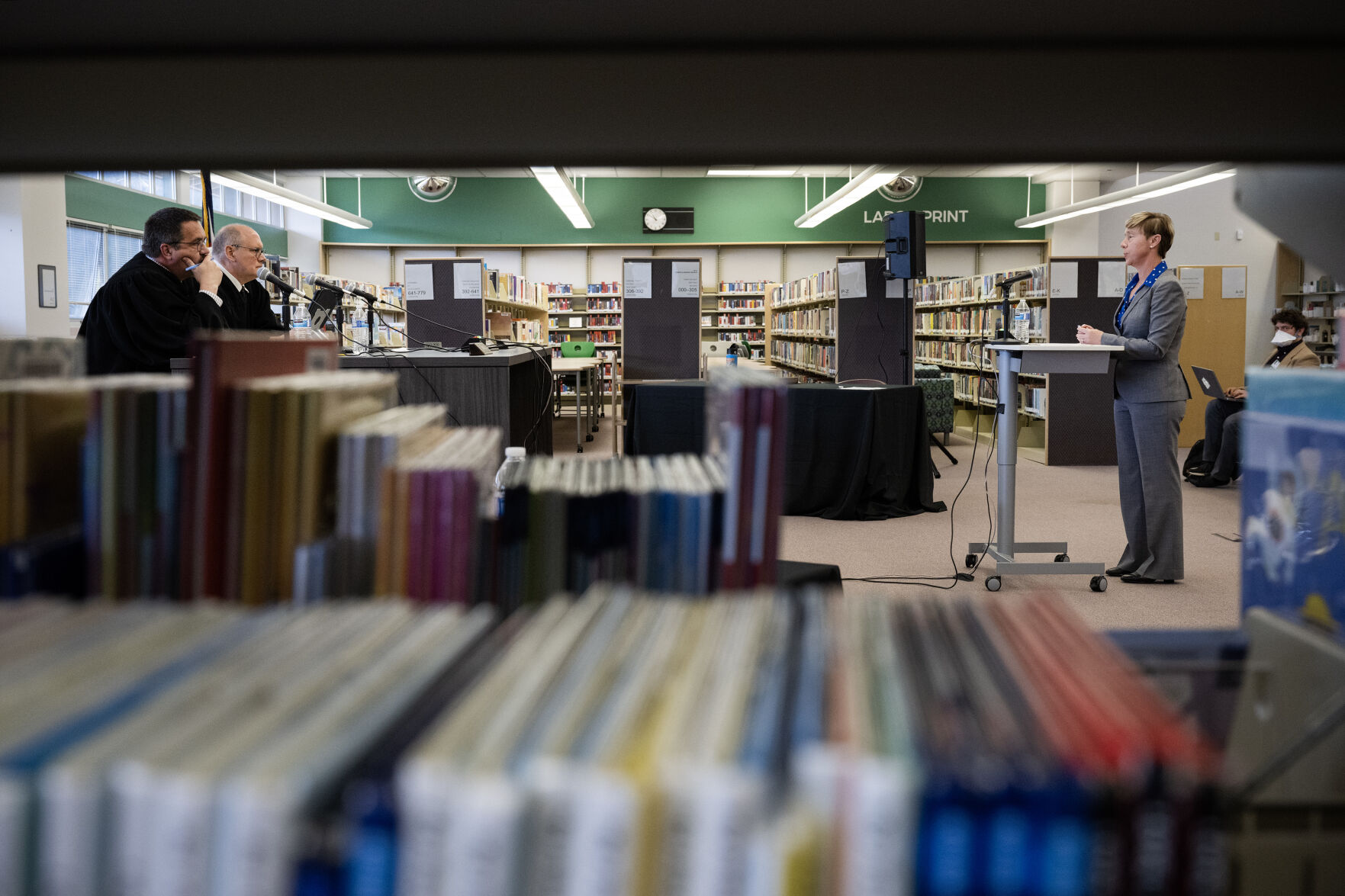

For a select group of attorneys who argued their cases before Colorado’s Court of Appeals on Tuesday, the experience was different in two key ways: First, they traded the ornate courtrooms of downtown Denver for the picturesque foothills 30 miles to the west.

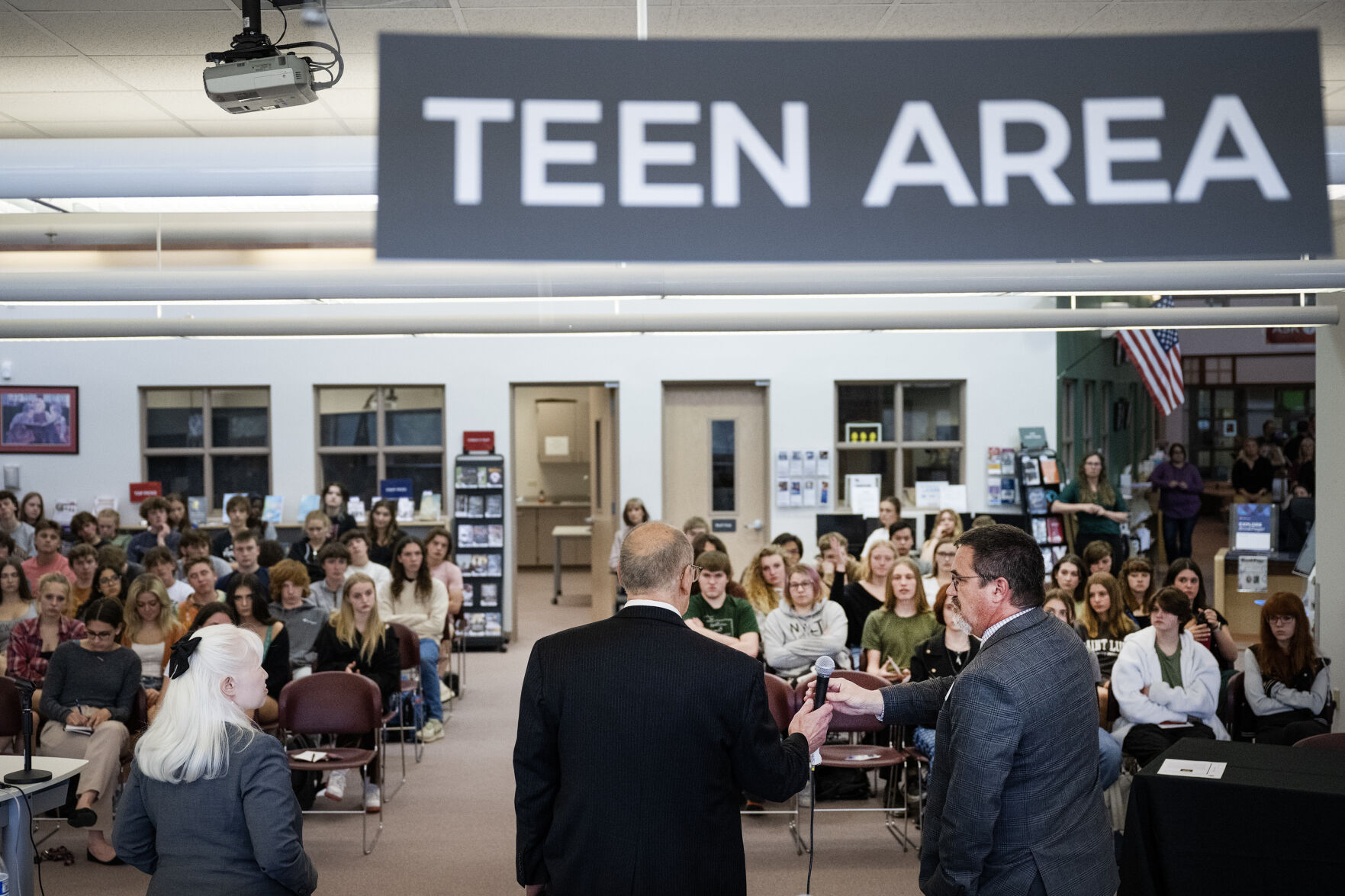

Second, the most pointed questioning did not necessarily come from the court.

“You guys are often way tougher than the judges are,” Assistant Attorney General Jaycey DeHoyos told students at Conifer High School.

As part of the judicial branch’s “Courts in the Community” initiative, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals traveled to Conifer to hear oral arguments in two real cases and then fielded questions from students. The judges explained their role in the justice system, which is to correct errors and clarify the law for the trial courts.

“One of the mistakes appellate lawyers make is they spend the first five minutes of oral arguments telling us how sympathetic their client is,” said Judge Ted C. Tow III. “I can’t consider that. The law is the law.”

The panel also contrasted Colorado’s merit-based method for selecting judges with both the federal system of lifetime appointments and the majority of states that fill their benches through elections. Judge Sueanna P. Johnson lobbed gentle criticism at the practice – seen most recently in a highly partisan Wisconsin Supreme Court race this spring – of judges “raising money and campaigning on how they would decide certain issues.”

“In Colorado, I think you would have a lot of the judiciary, if you went to a partisan election, not wanting to become judges,” she said. “At least to me, that seems anathema to what we’re supposed to be doing – and having independence and trying not to be biased and commenting about decisions that come before you.”

The first case the panel heard, Jansma v. Colorado Department of Revenue, involved a woman arrested for impaired driving whose driver license then became subject to revocation. A hearing officer upheld the revocation based on a finding that Maggie Jansma refused to take a test for her blood alcohol level. The only evidence was an officer’s report, issued one week after the traffic stop, with a box checked for “refused” and no elaboration about Jansma’s refusal.

“Sometimes I will focus on facts that help the judges keep their ruling, the impact of it, limited to just this case or very few other cases,” said Sarah Schielke, the attorney representing Jansma. “The preference in our system of justice is to have judge-made law progress incrementally and not with big sweeping change.”

Assistant Attorney General Danny Rheiner, arguing for the state, was asked why he ended his argument early, with several minutes left in his allotted 15 minutes.

“I was pretty much through my outline and I don’t think you wanna stay up there for longer if you don’t have anything to say,” he responded. Rheiner added that he often has a good sense of whether he is likely to win a case, but “I’m gonna be totally honest with you guys: I have no idea on this one.”

The other case, People v. Bialas, was the second time Michelle Re Nae Bialas had her claims heard before the Court of Appeals. After a jury convicted her of assault in 2017, the Court of Appeals ordered a new trial. At the second trial in 2021, a Gilpin County judge ejected her family members from the courtroom, telling them to watch remotely from a different room. The judge did not find Bialas’ supporters were responsible for misconduct, but rather the “best, easiest” rule was to have no spectators in the courtroom.

In arguing the judge violated Bialas’ Sixth Amendment right to a public trial, public defender Meredith K. Rose told the panel that the Courts in the Community event itself illustrated remote viewership is not a substitute for letting people watch legal proceedings in person.

“It’s a lot more nerve-racking to appear in front of such a large crowd,” she explained to students afterward. “But I did come to see it as an advantage. It would be hard for the Court of Appeals to go back and say there really isn’t a difference between being in person and being on a livestream – when we came here for a reason today.”

“I thought that was a really persuasive argument to make,” DeHoyos complimented her, after arguing in favor of upholding Bialas’ convictions.

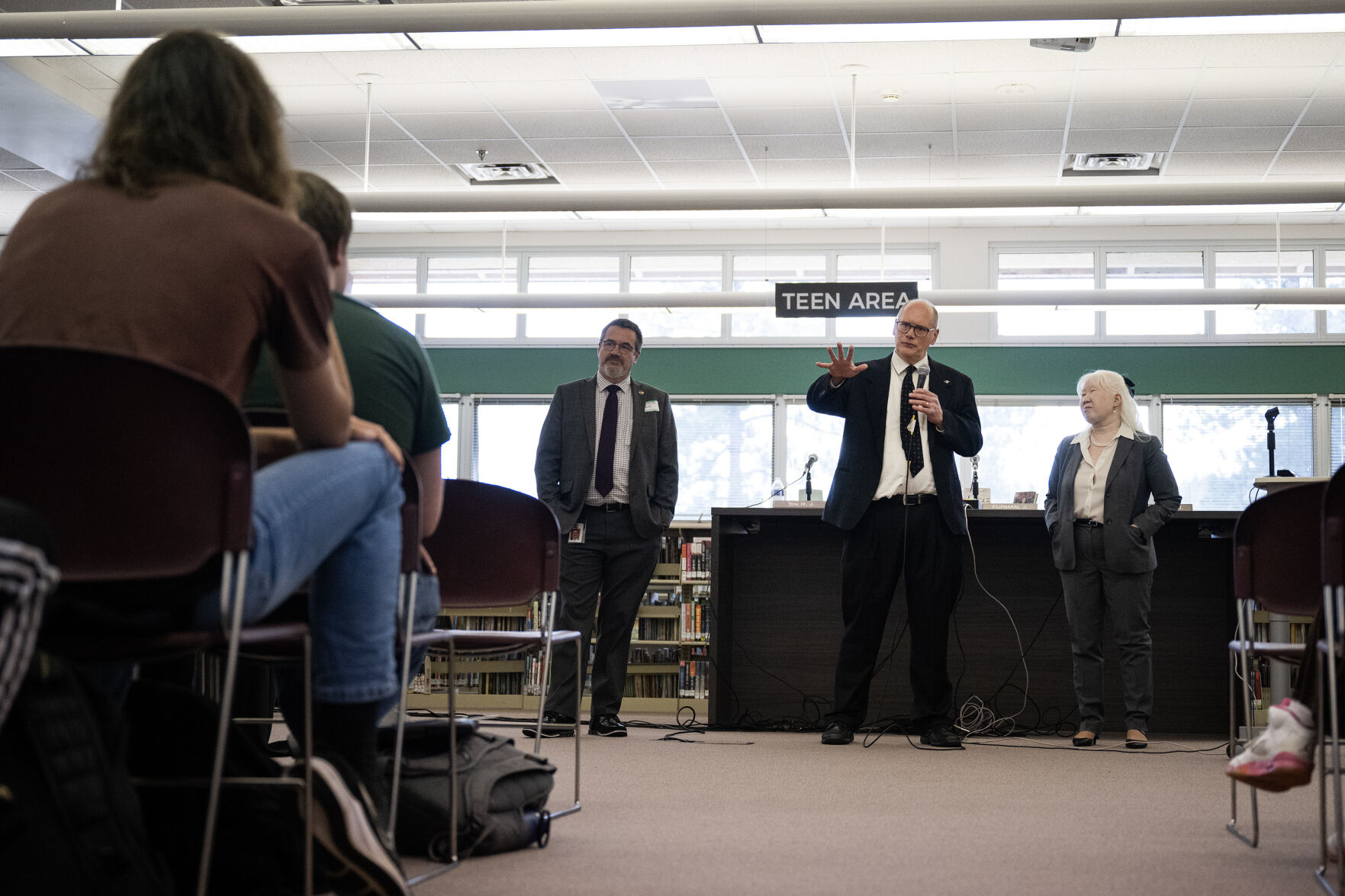

Following the arguments, the judges engaged in their own question-and-answer session, where they addressed their philosophy on grilling the attorneys.

“I tend to wanna let them present,” said Judge David Furman, who formerly coached basketball at Conifer. “I usually have one or two questions that gets to the heart of my concern.”

Tow answered that he was “on the other end” of the engagement spectrum, preferring to hone in on questions he needs the parties to answer before he can decide a case.

Johnson, the newest of the three judges, said she does not tend to ask many questions – a choice that drew the attention of the citizen-led commission in charge of reviewing her performance.

“They were like, ‘We don’t see that you ask a lot of oral argument questions’,” Johnson recalled. “I realized: That is the time when counsel knows that I have been engaged and I have reviewed the materials and I’m prepared. That’s why I at least ask one or two questions.”

Some of the lawyers who argued to the panel suggested they would be interested in having the ultimate decisions “published” – meaning they create binding precedent for trial judges to follow. The panel disclosed that the 22-member Court of Appeals commonly discusses how much they should be publishing opinions.

“There’s a real debate about that because trial judges would like us to publish more to give them guidance,” said Johnson.

Alex Miller, who recently finished his senior year but returned to witness the arguments, said he has an interest in becoming a lawyer and, specifically, being an appellate judge one day.

“I think I can impact more change being a judge and it just interests me more, overall,” he said.

History teacher Owen Volzke, who helped coordinate the event at Conifer, credited facilities workers with transforming the school’s library into a place that felt like a courtroom. Volzke said he gave students a preview of the cases and encouraged them to write questions down beforehand. He was impressed with the students’ contributions.

“We often talk about how what we do in the classroom ripples into the real world,” he told the audience afterward. “So hopefully you understand the crossover between everything we’ve been talking about and what you saw here.”