Colorado Supreme Court ponders role of juries in evaluating prior convictions

More than two years ago, when the Colorado Supreme Court found that juries, not judges, must decide if people accused of felony drunk driving are repeat offenders, it prompted defendants found guilty of other offenses to wonder whether their own prior convictions were something prosecutors must prove to juries beyond a reasonable doubt.

In two instances where prior convictions raise the severity of the crime under Colorado law – animal abuse and failing to register as a sex offender – the state’s Court of Appeals answered no, that judges alone can decide the defendant’s recidivism merits an enhanced sentence.

On Tuesday, Colorado’s highest court considered whether such a practice actually violates the federal or state constitutions. The justices acknowledged that currently, a judge may take a jury’s verdict for a misdemeanor and transform it into a felony conviction, solely based on priors.

“If we say the jury doesn’t get to decide a question that has remarkable consequences for a defendant, lifelong consequences,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel, “why is that OK to take that away from a jury?”

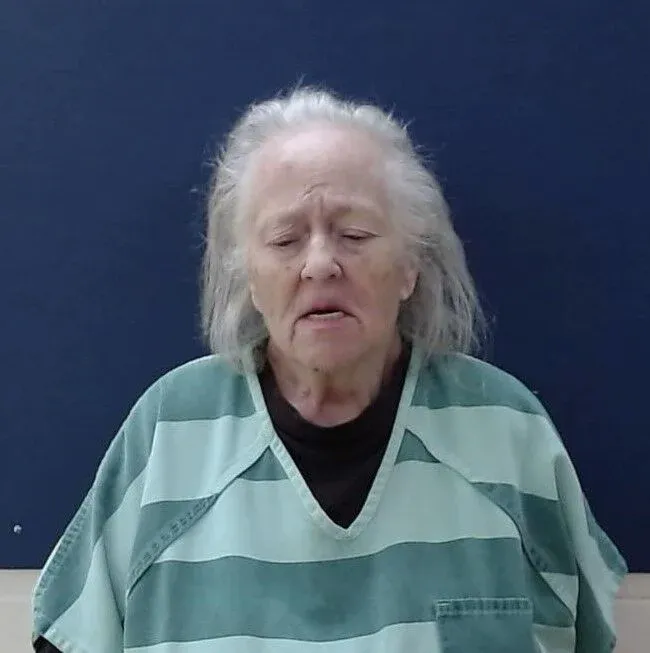

The Supreme Court heard two cases that involved similar circumstances. A Lincoln County jury convicted Constance Eileen Caswell of 43 counts of animal abuse, which is ordinarily a misdemeanor. Caswell admitted she had a prior animal abuse conviction on her record, prompting the trial judge to sentence her for a felony – as Colorado law requires for repeat offenses.

In the second case, a Denver jury convicted Charles K. Dorsey for failing to register as a sex offender. Twice in 20 years, he did not register by the annual deadline, which is a class 6 felony. After a jury convicted Dorsey the second time, prosecutors showed the trial judge paperwork documenting his prior conviction and the judge sentenced Dorsey on a more serious, class 5 felony.

Caswell and Dorsey’s appeals implicated four intersecting cases from both the state and federal Supreme Courts decided over a span of 25 years:

? Almendarez-Torres v. United States, in which the U.S. Supreme Court explained in 1998 that prior convictions could be used to enhance a defendant’s sentence

? Apprendi v. New Jersey, two years later, stated any fact that increases punishment for a conviction beyond what the law provides must be proven to a jury – except prior convictions (known as the “Apprendi exception”)

? Linnebur v. People, a 2020 decision of the Colorado Supreme Court, determined prior drunk driving convictions must be proven to a jury based on the state’s DUI law, and were not sentence enhancements for a judge to apply after the verdict

? People v. Kembel, decided earlier this year, clarified that when a defendant is on trial for a felony DUI in Colorado, jurors must hear about the current drunk driving offense and the prior drunk driving convictions all at the same time

Taken together, the cases suggest that while legislatures may structure laws differently to make prior offenses part of the sentence or part of the charged crime, the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial places a limit on the types of evidence judges can use to increase punishment after the jury’s verdict.

The state’s Court of Appeals, in examining Caswell and Dorsey’s convictions, decided that unlike the felony DUI law, the legislature had clearly intended for prior convictions to be sentence enhancers for animal cruelty and failure to register as a sex offender. Consequently, it did not examine the constitutionality of allowing a judge to transform a misdemeanor to a felony or a felony to a higher class of felony.

On appeal to the state Supreme Court, the defendants argued that Apprendi and Almendarez-Torres did not directly address the practice of enhancing a sentence using prior convictions, and the U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled on the propriety of a judge alone elevating a misdemeanor to a felony.

“It does not comport with the Sixth Amendment to block the jury from performing its vital function,” argued public defender Jessica A. Pitts, with a conviction that “transforms a person into a felon, a scarlet letter they will wear for the rest of their life.”

She pointed out that, in addition to harsher sentences, felons encounter “collateral consequences,” like restrictions on firearm ownership and difficulty obtaining housing or employment due to stigma.

Pitts added that, legally, the U.S. Supreme Court appears interested in walking back the Apprendi exception for prior convictions. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in 2005 that criminal defendants have been “unconstitutionally sentenced” thanks to the original Almandarez-Torres rule, and he supported reconsidering it. Last year, Justice Neil M. Gorsuch warned there was “little doubt” the court would have to address the constitutionality of sentencing based on prior offenses.

Public defender Meredith K. Rose, representing Dorsey, speculated the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet addressed whether juries must consider recidivism because the issue contains a “double-edged sword.” As Colorado’s Linnebur and Kembel cases showed, jurors may be required to hear damaging information about a defendant’s criminal history across a range of offenses, perhaps making convictions more likely.

“There are fairness questions on both sides,” she said. “Whether the defendant is deprived of his right to a jury trial on something that’s so important as to raise the felony level of the offense, versus, do we want these things to be proved to a jury?”

Caswell and Dorsey’s attorneys explained, however, that if jurors are asked to decide the existence of prior convictions, they may ultimately find the defendant sitting in front of them did not commit a prior offense beyond a reasonable doubt.

Gabriel believed the defendants were correct that the U.S. Supreme Court appears increasingly less willing to tolerate withholding evidence of recidivism from juries when used to change the offense level itself.

“If the Constitution says the defendant has the right to a jury trial, it doesn’t matter that there may be consequences the defendant doesn’t like,” he said.

The cases are Caswell v. People and Dorsey v. People.