Recreating Main Street: How Erie is using local control to solve its affordable housing problem | COVER STORY

Imagine walking out your front door, and five minutes later, walking into work.

Or a park.

Or the grocery store.

Or a doctor’s office.

Or hopping on a commuter rail to head into Denver.

That type of “Main Street” is what some in Weld County envision as the model for resolving a whole host of critical needs as America enters the mid-21st century – from a drier climate to traffic congestion to affordable housing to workforce development – and to do it without the state imposing changes on zoning, building codes or any of the other myriad ideas surfacing at the Colorado state Capitol.

At the core of that vision, they say, is a robust approach to resolving Colorado’s housing crunch, which is hitting rural communities like Weld County even harder than the state’s urban centers. That approach, they add, does not need to wrest away local control from municipal and county governments.

Weld County is offering its set of solutions to its housing woes as a sensible paradigm, even as state leaders and municipal and county governments prepare for a major battle over local control.

Gov. Jared Polis laid out the contours of that fight during his State of the State address in January, when he mentioned housing 37 times and argued the state needs “more housing for every Colorado budget, close to where jobs are.”

Indeed, he wrapped housing around a series of solutions to all kinds of problems: “Housing policy is climate policy. Housing policy is economic policy. Housing policy is transportation policy. Housing Policy is water policy.”

To make that happen, the governor called for “more flexible zoning to allow more housing, streamlined regulations that cut through red tape, expedited approval processes for projects like modular housing, sustainable development, and more building in transit oriented communities.”

The governor also pointed to efforts in communities, such as Greeley and Breckenridge, as examples of what those solutions could look like.

But he unequivocally signaled that the solutions require state intervention into policies traditionally under the sole purview of local governments.

And several Republican and Democratic legislators agree with the governor.

The Colorado Municipal League, which represents 272 towns and cities across the state, said it would oppose preemption of local authority to craft comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances or “one-size-fits-all approaches” to zoning the groups fear would disregard community needs and lead to displacement of residents.

The group said it would also oppose “unfunded mandates” or restrictions on cost recovery that require municipalities to bear the direct and indirect costs of development, as well as restrictions on managing development that would prevent them from ensuring they can provide adequate services for residents and manage their staff resources.

The group said instead, state policy leaders should consider these principles when tackling Colorado’s acute housing shortage:

-

Inclusionary zoning, approved by the General Assembly through House Bill 21-1117, which allows local communities to require developers to include affordable housing in their plans

-

Public and private sector support for housing

-

Using existing state resources to help local governments increase planning capacity and update land use practices

Colorado’s housing needs are acute. One study says that, just in the past seven years, the cost to buy a home has doubled, with half of that spike occurring in the last two years, even as household income has not kept pace.

Consider this: Through 2021, the housing deficit stood between 25,000 and 117,000 units and the state needs 20,000 and 46,000 permits each year through 2025 to close that gap.

Lawmakers are slowly rolling out their ideas on how to make housing affordable, such as rent control and more support to prevent evictions, although the bill – or bills – to put Democrats’ affordable housing solutions on the table are still being written.

In the meantime, Erie, in Weld County, is already planning on much of what the governor called for in his speech – and even more than the examples he cited – to craft affordable housing solutions.

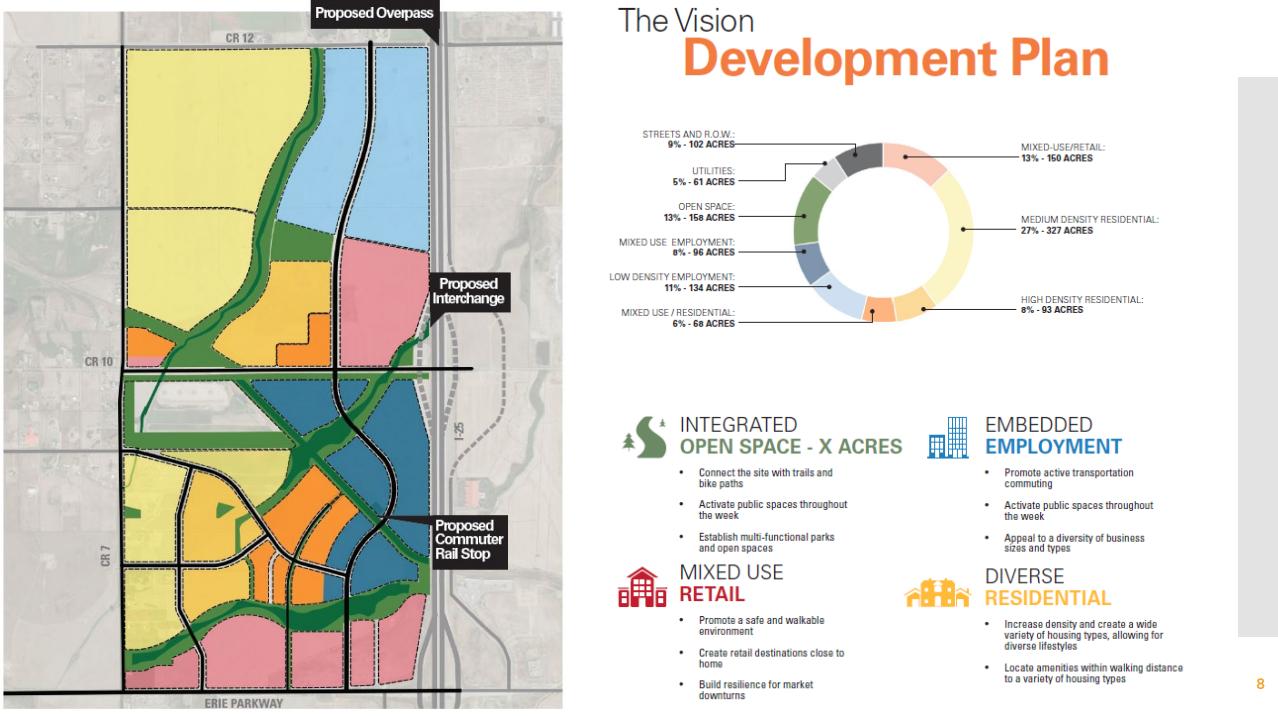

Gateway development

The Gateway development, for example, which has begun to take shape along I-25, just north of the Erie Parkway interchange, intends to bring in housing that supporters say almost anyone could afford, along with jobs, multimodal transit, open space and more.

In fact, town leaders in Erie began looking at the affordable housing problem nearly a decade ago, and those efforts began to take shape in 2018, when the town bought 255 acres of land just north of Erie Parkway.

The vision is to create a “regionally-scaled retail” and employment center at Erie’s eastern gateway, which will then service the Northern Colorado market. The idea, the town said, is to maximize the site’s revenue generating potential and employing “sound land use and high quality design principles.”

The town has grown exponentially in the last 30 years: 1,258 residents in 1990 to more than 28,000 in 2020. Town officials believe the population will reach 68,000 in the next 20 to 30 years.

And while the Gateway site is in a path of growth, according to one report, development along the I-25 corridor has not yet reached Erie, either from the north or the south.

Sarah Nurmela, the director of planning & development for the Town of Erie, recently said the Gateway project is an example of her community “driving the bus.” She added the town is inviting development partners and other property owners to get on board, with the goal of building an enterprise to attract investment, both by the development community and hopefully by transit agencies, including the Colorado Department of Transportation and the Regional Transportation District.

“We’re trying to talk about how the local level of control – the local decision-making – can yield a place like this without the initiatives” being discussed at the state Capitol, said Carlos Hernandez, the principal transportation planner for Erie. He noted in a Feb. 7 meeting at the state Capitol that the town showed off what it is doing to the governor’s office in early February.

“We want to be a model for the state of Colorado on how local communities can address some of these topics in the way that is local control,” Hernandez added.

If the governor wants to champion attainable and affordable housing, this is the way to do it, said Weld County Commissioner Lori Saine, adding it’s the right approach “if you care about attainable housing” and the push to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which comes mostly from cars, and provide a place where people can live closer to work, supermarkets or doctor’s offices.

“This kind of careful planning – where they’re making a new Main Street, where you shorten the distance between where people live, work and play – is best of all worlds,” she told Colorado Politics.

Saine noted that most of people’s incomes go to the house payment, and this type of development reduces the need for a car, which Polis also champions. To do that, she said, it needs to be a place where people can access a bus, walk, bike or use a car with shorter connections, you make it more affordable.

“All the things the governor is talking about, Erie is doing, and doing it correctly,” Saine said.

The Housing Challenge

The Town of Erie has only 12 housing units considered affordable, and all of them are for seniors, according to a recent grant application to the Department of Local Affairs.

Most of the town’s homes require a household income of at least $150,000 per year.

“Aging households, as well as local workers and service providers, are the most challenged to find housing options in Erie, particularly those with household incomes of $75,000 or less. In fact, less than three percent of housing units in Erie are affordable to households at this level,” the grant application noted.

“As the town continues to grow and population ages, both seniors and workers from healthcare to schools and retail will need to find options within Erie,” the application said, indicating those options don’t currently exist.

While state lawmakers hope to set up public-private partnership for affordable housing, with state-owned land as the site for some of those developments, Erie is already well on its way with a public-private partnership for the Gateway project.

The land purchased by Erie, combined with another 1,225 acres of privately-owned land, is slated to become the site for the Gateway project.

The development is bisected by County Road 10, close to the site for a new, planned I-25 interchange.

It includes more than 400 acres devoted to medium- and high-density housing, such as apartments, condos and townhouses, some as high as four or five stories, with retail and businesses on the first floors.

It’s not the only effort in Weld County to address affordable housing issues.

In Frederick, a town master plan for diverse housing stock proposes a mix of smaller-scale homes and units, designed to cater to residents, especially seniors, looking to downsize.

The Affordability Challenge

Erie faces a perfect storm of affordability challenges, according to a Nov. 10, 2022 report from a consultant hired by Erie to analyze strategic housing options.

The town is located in a “strong-market community in a strong-market region,” meaning mostly upper income homes. Most of the housing stock is owner-occupied, single-unit detached houses, and built with new construction.

That’s meant that anyone looking for a home at less than $500,000 should look elsewhere.

If Erie were to make any progress on housing affordability, said the report from czb, the consulting firm, “it will need to diversify the housing stocks,” including for price point.

But even rentals are out of reach for all but high wage earners, the report said. The town should anticipate a two-bedroom rental unit to cost $350,000 to build, and with construction costs on the rise, that’s a lowball figure. The average monthly rent for an apartment at that price point is $3,500 per month, requiring an annual household income of at least $140,000, the report said.

Part of the solution is to lower development costs. Developers can adjust for variables such as land, materials, labor and financing. What makes Erie’s plan workable, however, is that the town holds the “lever” on land use controls that can dictate how many units can be built per acre.

For example, a $1 million acre of land could hold five units, or it could hold 25. At 25 dwelling units per acre, that drops the income requirement below $100,000 and starts to approach affordability, which in the report estimated at $75,000 per year.

The town council recently reviewed an inclusionary zoning ordinance, allowed under the 2021 legislation. That zoning requires developers to provide some portion of new units as affordable, and the town decides what affordable means.

It does mean Erie will have to find money to subsidize that development, the report said.

The Transit and Business Challenge

According to a 2018 report from Design Workshop, an urban design company, 90% of local residents work somewhere other than in Erie. The town commissioned the report.

As a result, almost 64% of spending from Erie residents also occurs somewhere other than Erie.

A gap in retail services exists, the report said, pointing to shopping available south of town, in communities like Broomfield, Boulder, Thornton and Westminster.

The Gateway project envisions retail, with housing layered on top of those spaces, to be located within the confines of the site. But it’s more than shopping – the site envisions businesses of all kinds, including industrial scale, and that means jobs, and walking or biking to work instead of driving to Boulder or Denver.

Businesses are choosing Weld County for expansion, but they aren’t yet choosing Erie, the design workshop’s report said.

Indeed, major industries, such as food, technology, aerospace and bioscience, are finding a home in Weld County, and Erie wants Gateway to be on their radar, too.

The site would include a network of pedestrian and biking trails, instead of using cars. That makes good business sense, too, according to the website conservationtools.org. Trails increase property values, boost spending at local businesses, make communities a more attractive place to live, and influence business location and relocation decisions.

The Gateway project has two major transit goals: Build a new I-25 interchange at County Rd. 10. The site is currently an underpass, with an I-25 interchange just south of the project at Erie Parkway. The plan indicates a new interchange would resolve some of the congestion problems on Erie Parkway.

The parkway has become a magnet for accidents. In 2017, Erie Police recorded 38 accidents at just one intersection – on Weld County Road 7 and Erie Parkway – immediately south of the Gateway site. A traffic signal was installed in 2020, but the accidents continue to pile up along the Parkway.

However, the interchange is likely a long-term solution that doesn’t fit within the five to 10-year timeline for Gateway, and the cost, estimated at $96 million, is also a downside, according to the design workshop report.

The second transit solution, a commuter or light rail, is also likely years off.

A Colorado Department of Transportation environmental impact study included in the design workshop report suggested “the maturation” of a commuter rail transit line with nine stations connecting Fort Collins to Longmont and Thornton along the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad easement won’t happen right away. That could include a station near Gateway, the report said.

“While unlikely to be realized in the next decade or longer, advanced planning would make for an easy transition when and if the rail line becomes active again,” the report said.

In order for all of this to work, town officials will have to make zoning changes at the site, which is forecast by the end of this year.

The Infrastructure Challenge

One issue the project will have to fix, and fast, is infrastructure.

Julian Jacquin, the director of economic development for Erie, told Colorado Politics the town is evaluating the feasibility of an urban renewal authority for financing infrastructure, which is why the project hasn’t yet gotten underway. Sanitary sewer is a few miles and a few years away, he said.

“The viability of the project” rests on getting sewer lines out to Gateway, which he said might take three to five years.

The site doesn’t have water, either, although there is a water main within Erie Parkway that would serve as the supply route for the south end of the site, according to the Design Workshop report and the water master plan.

The master plan envisions a future water trunk line along Weld County Road 7, which would tie into the project, along with a mix of short- and long-term wastewater systems.

The town’s 2021 water plan integrates water efficiency with land use planning. That would provide both cost savings and efficiencies by reducing the need for converting turf to low water use landscapes or indoor water use retrofits in plumbing, for example.

However, low water use landscaping isn’t off the table, and the town water plan calls for it on public owned spaces, while respecting “individual community resident preferences within reason.”

The infrastructure challenge also includes roadways.

Jacquin said the town is working with Dacono and Frederick, on the other side of I-25, on improvements to Highway 52, on the north end of the Gateway site, which he said will provide immediate benefits to all three communities. Those improvements would make both sides of I-25 more attractive to development, he said.

The project is in planning and design now, including conversations with private property owners on either side of the development site, Jacquin said.

Officials hope to have the town-owned property – that 255 acres that is mostly going to contain open space and medium- and high-density housing – built out within five years.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

North Station Concept Plan – CDG.pdf