Divided state Supreme Court says juries may hear defendants’ drunk driving histories

A majority of the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday that juries must learn about a defendant’s prior drunk driving offenses at the same time they hear the current allegations of drunk driving, over the strenuous objection of three justices who said the move all but ensures a conviction will occur.

By 4-3, the Supreme Court addressed the latest issue in the fallout from its own 2020 decision to declare prior convictions an element of felony driving under the influence, rather than a factor that only affects sentencing. Left unanswered was whether judges should hold “unitary” trials, where prior offenses and the current offense are presented together, or “bifurcated” trials, in which priors are heard after jurors decide whether a defendant is guilty of the current offense.

The court’s majority sided with unitary trials, citing its own precedent, smooth administration of justice and jurors’ own personal lives.

“In a felony DUI trial in which the elements are bifurcated, as jurors complete deliberations on the elements of DUI, they no doubt would start making plans to resume regular life,” wrote Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. The jurors might have to “cancel those plans so they may continue serving.”

Justice Richard L. Gabriel dissented, believing the majority’s logistical concerns did not outweigh the risk of jurors convicting a defendant because of a belief that he or she is a habitual drunk driver.

“The majority’s opinion thus virtually assures a conviction in every felony DUI case because I do not believe that even the most diligent and responsible jurors would be able to set aside in their minds (or limit their consideration of) the fact that a defendant has been convicted multiple times of the same offense that they are considering,” Gabriel wrote for himself and Justices William W. Hood III and Melissa Hart.

The latest decision raises the question of whether defendants accused of felony DUI are now in a worse position than before the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Linnebur v. People.

The legislature created a felony drunk driving offense in 2015 that would apply when a person has at least three prior DUIs, which are ordinarily misdemeanors. The sponsors of the legislation understood the prior offenses would serve to enhance the fourth DUI to a felony after trial, with a more serious sentence to follow.

But in Linnebur, the court decided, 4-2, the priors were actually elements of the felony DUI charge and, thus, need to be proven to a jury at trial. Justice Monica M. Márquez, who dissented from the decision along with Samour, warned that the Supreme Court had opened the door to juries hearing damaging information about a defendant’s drunk driving history.

“Today’s decision strikes me as an example of ‘be careful what you wish for’,” she cautioned.

Since then, the Supreme Court has had to clarify the effect of Linnebur, ruling in December 2021 that prosecutors may retry defendants for felony DUI whose convictions were on appeal when the decision came down. Then, in October, the justices heard arguments over whether bifurcated trials were necessary for felony DUI.

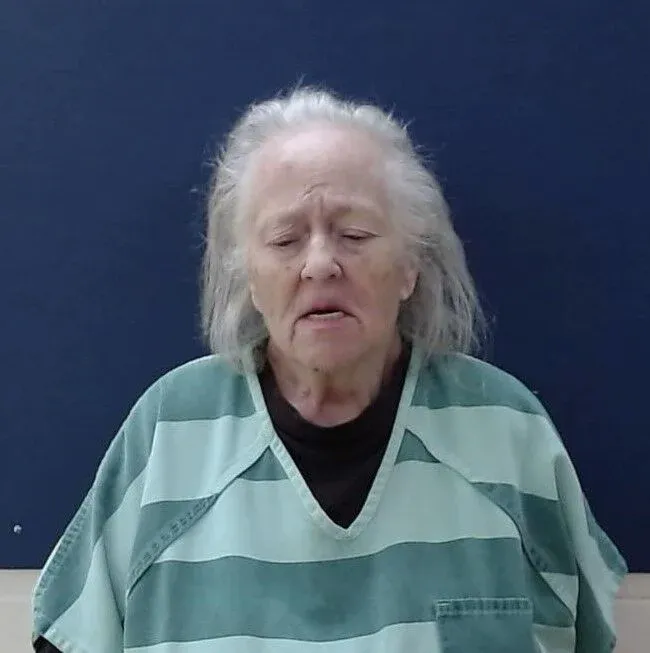

Prosecutors in Larimer County appealed directly to the Supreme Court in the cases of two defendants, Timothy Albert Kembel and Kerrie Lyn Dexter. District Court Judge Sarah B. Cure granted the defense’s requests to bifurcate the trials based on her reading of caselaw.

“The Court does think that the prior convictions impacts this defendant’s right to a fair trial, an impartial jury,” she said.

On appeal, the discussion centered around a 50-year-old Supreme Court case, People v. Fullerton, decided in 1974. In a rough parallel to felony DUI, the defendant in Fullerton was convicted of possession of a firearm by a prior offender. The court decided simultaneously that bifurcating elements of an offense is improper, but also that the administration of justice “must be weighed against” any prejudice to defendants from airing information about prior misconduct.

During oral arguments, some justices were skeptical that Fullerton provided an answer for felony DUI. Hart pointed out that if someone is convicted of driving under the influence in the first phase of a bifurcated trial, but the prior offenses are not proven later, they remain convicted of a misdemeanor. That was not true of illegal weapons possession.

“Possession of a weapon isn’t illegal unless you’re also a prior offender. So bifurcating them just isn’t possible,” she said. “Here, having a trial as to the underlying DUI, you can do that with no trouble and have the second part of the trial talk about whether there are three prior convictions.”

But the court’s majority ultimately disagreed. It found Fullerton did apply and, moreover, flat-out prohibited bifurcating felony DUI trials. Samour wrote about the “significant disruption” that bifurcation would cause to jury trials, alleging problems with instructing jurors, screening jurors for bias and “deceiving” them about the charged offense.

He explained the legislature is “certainly free to clarify” that prior DUIs are a post-conviction sentence enhancer, and not an element of a felony DUI offense to be proven to a jury at trial. But until then, trial judges need to treat priors as an element.

“Our jurisprudence is clear that an element is an element is an element. There are no part-time elements,” he wrote in the Jan. 30 opinion. “Once a fact is endowed with elementhood, it can’t be treated as something else.”

Gabriel’s dissent slammed the majority’s “unfounded concerns” and “fundamentally flawed” interpretation of Fullerton.

“Lost in the majority’s reasoning, however, is the immense injustice that its decision will cause Kembel, Dexter, and felony DUI defendants throughout this state,” he wrote for the dissenting justices. “Although I have great faith in juries in our system of justice, it belies reality to suggest that a person charged with a felony DUI will receive a fair trial when the jury hears about their three (or more) prior convictions of the same charge.”

Gabriel added that whatever concerns the majority had about the administration of justice, other states had surmounted and Colorado’s trial judges could similarly adapt. He suggested that if a jury acquitted a defendant of driving drunk in the first phase of a bifurcated trial, jurors would not need to decide the existence of prior offenses and could leave sooner.

Abe Hutt, an attorney specializing in DUI defense, said the decision increases prosecutors’ leverage and makes it easier to convict defendants of felony DUI now than before Linnebur was decided. Hutt did not know whether lawmakers would want to overturn the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the felony DUI law and return it to a sentence-enhancing tool.

“Certainly my fear is there will be enough people in the legislature that are just fine with the Supreme Court making it easier to convict people that there’s not necessarily gonna be a whole lot of appetite to change it,” he said.

On Tuesday, District Attorney Gordon McLaughlin, whose office appealed the cases to the Supreme Court, said the ruling creates consistency across trial courts and enables jurors to better understand their responsibilities in felony DUI cases.

“While it does not put either party in a better or worse position, it does honor Colorado Supreme Court precedent and the intent of the legislature when they created the felony DUI offense,” he said.

The cases are People v. Kembel and People v. Dexter.