Cause of Marshall fire remains a mystery a year after blaze scarred public and 6,080 acres

It is indisputable that the Marshall fire in Boulder County, which damaged and destroyed 1,169 homes last year, is one of the most devastating in Colorado’s history.

What remains in question – a year after the Dec. 30, 2021, fire scorched 6,080 acres – is how the blaze started and where.

The Boulder County Sheriff’s Office has yet to determine a cause.

Colorado to distribute $6 million to Marshall fire victims rebuilding homes

A Sheriff’s Office spokesperson did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails from The Denver Gazette seeking comment.

In a Dec. 15 news release, officials said they intend to release the cause and origin report early next year.

The news release outlined the investigation efforts, notably sorting through hundreds of tips, scouring hours of body-camera footage and processing almost 200 pieces of evidence. The release listed possible causes of the mega-fire: debris burning, underground coal-mine fires, children playing with matches, fireworks and the potential of an equipment malfunction or spark.

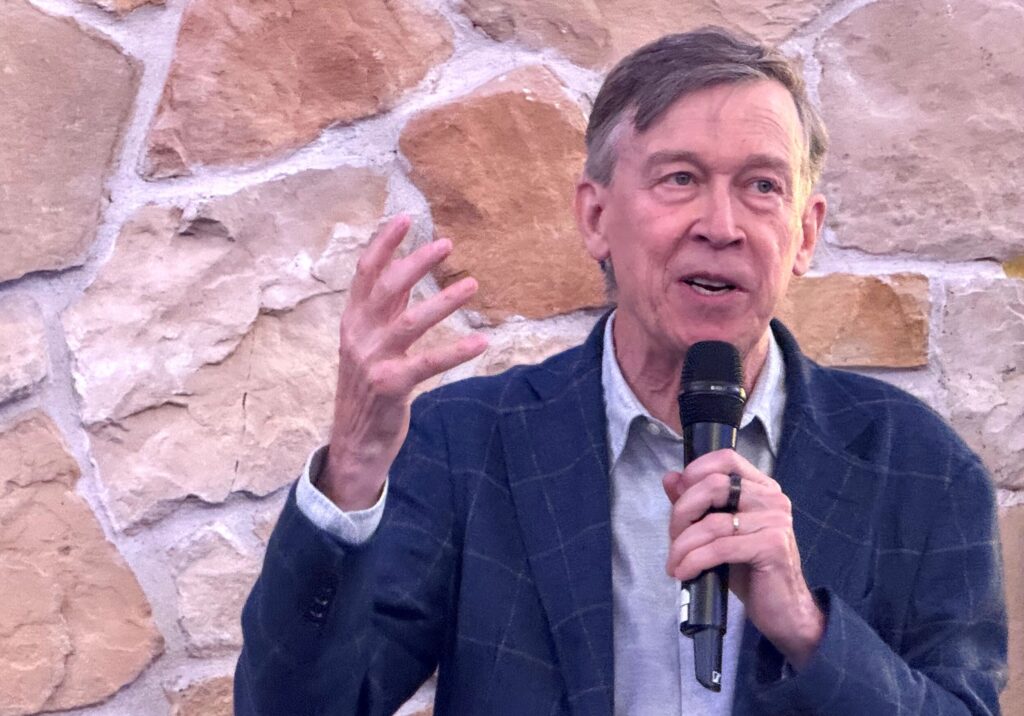

“It is surprising we have reached the anniversary and the public still doesn’t know the cause of a fire that was so devastating,” state Sen. Kerry Donovan, D-Vail, said.

This year Donovan introduced a bill that would – had it passed the Legislature – have tasked the Division of Fire Prevention and Control within the Department of Public Safety with investigating wildfires and collecting data to prevent future fires at an annual cost of $3 million. Part of that money would be used to fund state costs associated with helping local fire departments in investigating the origin and cause of fires.

A Superior effort: Lessons learned through resiliency of rebuilding after Marshall fire

“Colorado has some of the lowest numbers reported in the West for the cause of wildland fires,” Donovan said. “This is largely because we have so few staff dedicated to investigating causes.”

The state employs one full-time fire investigator.

“DFPCs role is to support local jurisdictions,” Caley Pruitt, a Colorado Department of Public Safety spokesperson, said in an email to the Denver Gazette. “At this time, with only one full time dedicated investigator, we do not have the capacity to take on fire origin and cause investigations for the entire state.”

The governor’s proposed budget adds seven investigators and funding to develop a data portal to support data collection, Pruitt said.

Under state law, local governments investigate the cause of fires that destroy or damage property. This often falls to sheriff’s offices. As a result, Colorado does not possess statistical data on fires outside its jurisdiction or those on state land.

“I thought we were missing a critical piece of the discussion,” Donovan said. “How can we reduce wildfires when we don’t know the cause?”

***If you don’t get to the origin, you’re just guessing***

Wildfires are typically caused by a natural occurrence, such as a lightning strike or human activity. But it’s weather conditions – wind, high temps and little rainfall – that determine how big a wildfire will grow.

Human-caused fires accounted for 87% of all wildfires nationally, according to the National Interagency Fire Center, which provides support for fighting wildland fires.

Although the state does not track this, a 2003 Colorado State University report for Larimer County found 11% wildland fires on state and private land were caused by lightning, 49% by humans and 40% unknown.

About 60% of Colorado’s 20 largest wildfires were caused by human activity, a Denver Gazette review of federal reports, press releases and media stories shows.

It is unknown whether human activity caused the Marshall fire.

The Marshall fire started on Dec. 30, 2021 as a wildland blaze but, driven by wind gusts of up to 115 miles an hour, quickly cut through the “communities of Louisville and Superior and over a six-lane highway,” according to the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office.

Colorado insurance recoveries up 93% due to wildfire claims

Pinpointing the origin of a blaze is the first critical step in identifying its cause, fire investigators told The Denver Gazette.

“If you don’t get to the origin, you’re just guessing at the cause,” said Tom Fee, a certified fire investigator in Southern California and past president of the International Association of Arson Investigators.

A fire investigation does not always yield an origin and cause.

The reason?

“By the nature of fires, they can burn up their own evidence,” Larimer County Sheriff Justin Smith said.

Larimer County has the unenviable distinction of having Colorado’s largest wildfire: the Cameron Peak fire, which charred 208,913 acres in 2020.

The scale of a fire can make identifying a fire’s cause and origin challenging.

The Boulder County Sheriff’s Office alluded to this when disclosing earlier this month that investigators have followed up on more than 200 tips, collected 186 pieces of evidence and reviewed hundreds of photos.

“When it seems to be simple, sometimes it’s not,” Smith said.

***The evidence changes***

Every fire is different.

But the method for investigating fires – whether in the mountains or in a subdivision – is the same.

The accepted scientific method includes collecting and analyzing data to develop and test working hypotheses.

The complexity and high-profile nature of the Marshall fire could have prompted investigators to deliberately move slowly and surely through the investigative process, fire experts the Denver Gazette interviewed said.

“I’ve never had an investigation go that long, but I’ve also not had a fire that complex,” Carrie Bilbao, a spokesperson for the National Interagency Fire Center in Idaho and a certified fire investigator with 26 years of experience, said of the Marshall fire.

The danger with an investigation that drags on – these experts said – is that evidence degrades and memories fade.

“The evidence changes,” said Fee, the California investigator. “The longer you take doing this, the less you have to look at. Your facts go away.”

A burnt power line, for example, will appear shiny. But in six months, Fee said, a that power line will begin to oxidize and in nine months identifying the clues a fire left behind can be tricky.

While a years-long investigation is irregular, it’s also becoming more commonplace for public agencies to take longer before issuing a cause, Fee said.

Fee has consulted on a couple Colorado wildfires, including the Hayman fire.

Despite having ignited two decades ago, the Hayman fire was so devastating it held the state record for the largest wildfire until 2020.

The Hayman fire licked up 137,760 acres in 2002 after a U.S. Forest Service employee burned a letter while patrolling for illegal campfires. The origin and cause for the fourth largest in Colorado history was determined within 60 days, Fee said.

But that was then.

Take the massive Thomas fire in Southern California. Started in December 2017, the wildfire burned for more than month, scorching 281,893 acres in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties before firefighters extinguished it. It destroyed more than a thousand structures and caused billions in damages.

It would take investigators 15 months to determine the cause: downed power lines.

The possible high stakes in a high-profile case has led some to believe the cause of the Marshall fire may remain unknown.

Frank Carroll, a private fire investigator in Pueblo with more than 30 years with the U.S. Forest Service, blames investigations helmed by political figures.

“Colorado has not been able to navigate the politics of wildfire,” Carroll said, adding, “It’s not just the sheriff. It’s the system in Colorado.”