Judge tosses attempt from Trump’s Colorado lawyer to avoid Jan. 6 committee’s subpoena

A federal judge has thrown out a lawsuit from one of former President Donald Trump’s lawyers in Colorado, who was seeking to avoid a subpoena for her phone records from the congressional committee tasked with investigating the deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Katherine Friess sued the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, alleging its request for her phone logs – but not for the content of any communications – went beyond the committee’s authority and infringed on her attorney-client privilege with Trump.

The committee, in turn, contended it could not be sued for issuing a subpoena, as it was carrying out a legitimate investigation into Friess’ reported attempts on Trump’s behalf to gain access to voting machines after the 2020 presidential election and to otherwise work toward overturning the election results.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Kristen L. Mix sided with the committee, recommending in October that Friess’ attempt to block the subpoena be dismissed.

“Plaintiff fails to direct the court’s attention to any case where the Select Committee’s investigation has been found not to further a legitimate task of Congress,” she wrote. Consequently, “the court finds that plaintiff’s phone records are not an improper source for the Select Committee’s investigation.”

Last Thursday, in a brief order, U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney adopted Mix’s recommendation in full.

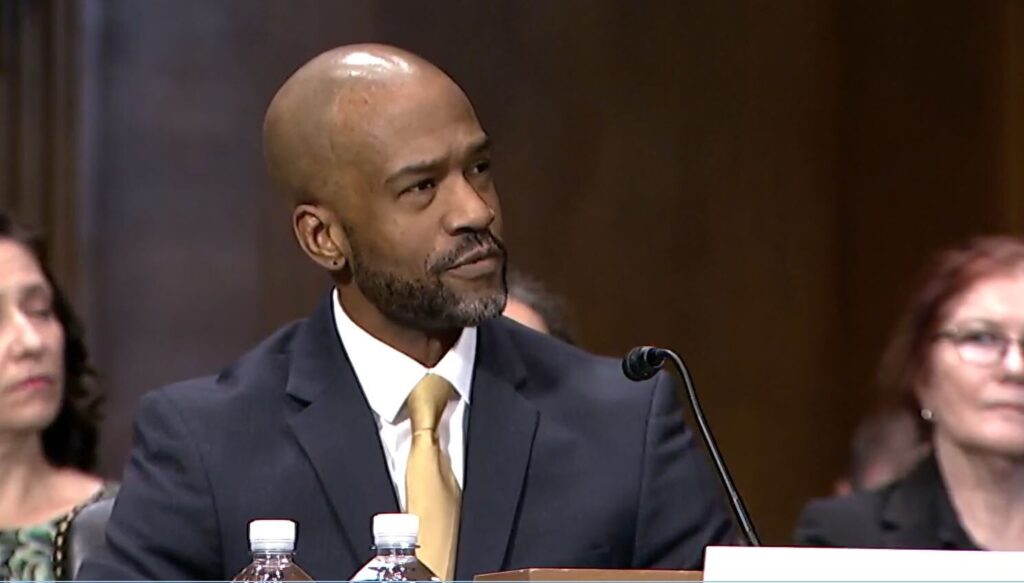

The U.S. House of Representatives voted to create the select committee to investigate the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol by Trump supporters seeking to prevent the certification of the presidential election, in which Joe Biden won the popular and electoral college votes. The House empowered the committee’s chair, U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., to issue subpoenas for information and testimony.

Friess, whose attorney registration in Colorado lists a business address in Vail, wrote in her lawsuit that she served as an “election integrity attorney,” and has worked for Trump since November 2019. After Jan. 6, media outlets reported on Friess’ involvement in Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 results. For example, Friess was connected to a draft executive order that would have enabled the federal government to seize voting machines, and urged local officials in Michigan to examine their equipment.

On Feb. 1 of this year, Thompson issued a subpoena from the Jan. 6 committee to AT&T, seeking call and text message logs from Friess’ phone account between November 2020 and January 2021. Thompson also sought testimony and documents from Friess directly.

“The Select Committee’s investigation has revealed credible evidence that you publicly promoted claims that the 2020 election was stolen and participated in attempts to disrupt or delay the certification of the election results,” Thompson wrote to her in a March 1 letter.

Friess then filed a lawsuit in Colorado, accusing the committee of overreach, of violating her attorney-client privilege by seeking to disclose her communications with clients, and of chilling her First Amendment right to speak about “the integrity of this country’s elections.”

“I revere our laws,” Friess wrote to the court. “I have been harassed, threatened, and libeled in recent weeks – including harassing phone calls to my clients and colleagues in pursuit of my location and contact information.”

The committee responded that longstanding precedent from the U.S. Supreme Court rendered Friess’ lawsuit futile. The Constitution provides for members of Congress that with “any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place.”

The Supreme Court, in the 1975 decision of Eastland v. United States Servicemen’s Fund, ruled that when Congress acts within its legitimate legislative functions, the speech or debate clause provides “an absolute bar” to judicial interference.

“Because the Select Committee’s subpoena to AT&T is within this approved, legitimate legislative sphere, the court may not interfere with Congress’s independence by entertaining Ms. Friess’s complaint,” wrote the committee’s lawyers.

Mix, in analyzing the legal arguments, rejected Friess’ characterization that the “data dump of an attorney’s smartphone” amounted to illegitimate activity on the committee’s part. She agreed the Eastland decision definitively shielded the committee from judicial involvement.

“In short, ‘the absolute nature of the speech or debate protection’ is not overcome by other protections in the Constitution,” the magistrate judge wrote.

Although the parties had 14 days to lodge objections to Mix’s conclusions, neither side did. Consequently, Sweeney, the district judge, promptly dismissed the case.

The committee to date has engaged in a series of televised hearings and obtained testimony from former Trump administration officials, election officials in swing states, a convicted participant in the Jan. 6 attack and law enforcement officers who were present that day. On Sunday, one member of the select committee, U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., told “Face the Nation” that members will release “all the evidence” prior to the new Congress in January.

“I think we’ve, as we’ve shown in our hearings, made a compelling presentation that the former president was at the center of the effort to overturn a duly elected election, assembled the mob, sent it over to Congress to try and interfere with the peaceful transfer of power,” she said.

The case is Friess v. Thompson et al.