Colorado Supreme Court’s frustration at state agency boils over in juvenile case

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court lashed out on Tuesday at the state agency responsible for overseeing certain mental and behavioral health services to juvenile defendants, accusing it of flouting the law.

In an appeal out of Weld County, the justices amplified their frustration with the Office of Behavioral Health that previously surfaced in 2019, when the court first appeared skeptical of OBH’s claims that it could not advise judges whether children receiving its treatment could stand trial.

Now, in the Oct. 4 decision of People in the Interest of A.C., three members of the Supreme Court reiterated their concerns about obstructionism after OBH refused to inform a juvenile court about the mental status of defendant A.C.

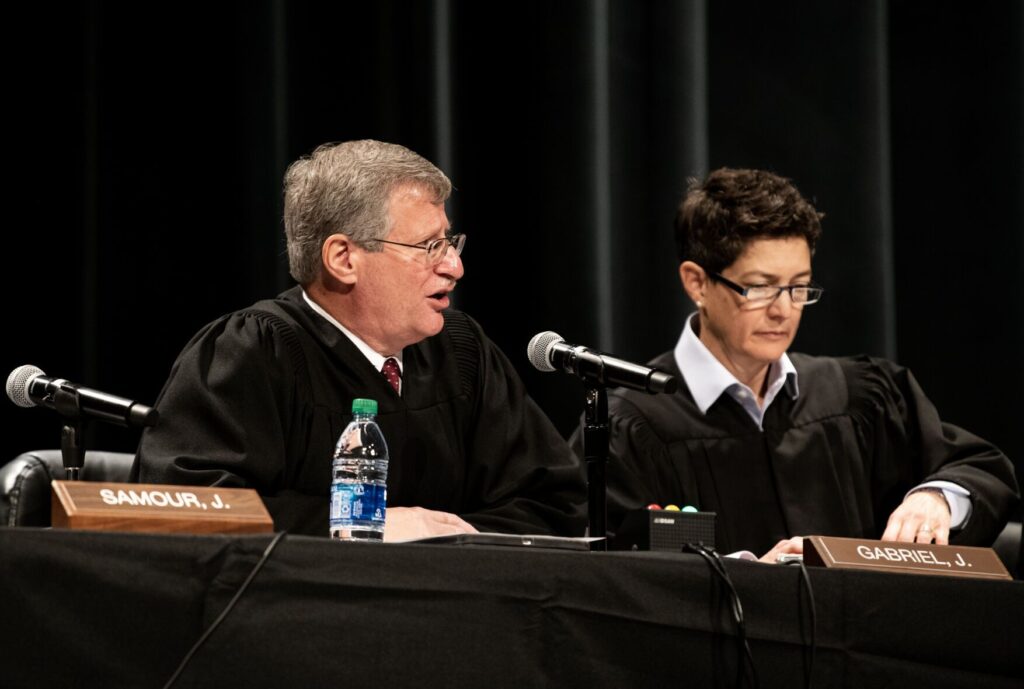

“OBH continues to prioritize its own policies over its duties” under the law, wrote Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. “OBH’s refusal to do what the legislature intended left the juvenile court hanging in the wind.”

Justice William W. Hood III, writing for himself and Justice Richard L. Gabriel, added that OBH is “continuing its policy of refusing to provide meaningful progress reports to the court, as required by law.”

OBH, which is now known as the Office of Civil and Forensic Mental Health, believes the criticism stemmed from confusion about its operations, and a spokesperson said the office “disputes any characterization that it is not satisfying its statutory obligations.”

Due process requires criminal defendants be competent to stand trial, meaning they do not have a mental or developmental disability that prevents them from understanding the proceedings or assisting in their defense. State law directs a psychologist or psychiatrist to evaluate a defendant’s competency to proceed when requested.

In the appeal before the Supreme Court, A.H. was charged with an unspecified offense and a magistrate ordered a competency evaluation based on the child’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. OBH was the entity responsible for coordinating the necessary services.

A doctor concluded A.C. did not have the ability to retain the legal concepts of his case, and therefore lacked the competency to stand trial. However, the doctor added that the prognosis was “fair to good” for restoring A.C.’s competency.

A.C. attended multiple sessions with treatment providers, who walked him through educational modules. One provider testified A.C. seemed to grasp the legal details, but neither she nor A.C.’s original doctor opined about whether A.C. had, in fact, been restored to competency. The magistrate, finding she had insufficient information, ordered a “reassessment” of A.C. to measure his progress.

The defense then appealed to the Supreme Court. A.C.’s lawyers leaned heavily on a 2019 decision from the court, People in the Interest of B.B.A.M. In that case, a majority of the justices found Colorado law did not permit juvenile courts to order a second competency evaluation for a juvenile defendant. A reassessment, A.C. contended, was essentially an illegal second evaluation.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter, writing for the court’s majority in A.C.’s appeal, noted that juvenile judges must track a defendant’s progress until they regain competency. The General Assembly, she explained, intended for judges to have the tools to determine whether a child ever reaches that point.

“Any reading of these statutes that does not grant juvenile courts this authority is illogical: It recognizes that the juvenile court has important obligations with respect to competency restoration, but then ties the court’s hands in any cases where restoration cannot be determined without expert testimony based on some degree of reassessment,” Berkenkotter wrote.

In an unusual move, Berkenkotter’s majority opinion was accompanied by three additional opinions from the other members. Her colleagues were less restrained in their criticism of the competency process, and they renewed their ire at OBH.

The B.B.A.M. decision originally recognized OBH had taken a position in court of claiming its service providers could not give opinions about juvenile defendants’ progress toward competency. Doing so would allegedly be a conflict of interest, requiring them to speak about the effectiveness of their own restoration services. OBH had only supplied the juvenile court with explanations that defendant B.B.A.M. was “progressing nicely” and was “motivated to become competent.”

Samour, who authored the majority opinion in B.B.A.M., suggested he did not believe the law or common sense allowed OBH to abstain from offering meaningful opinions.

“In our view, any individual agreeing to provide competency restoration services does so with the expectation that he or she will report to the court the juvenile’s progress toward competency,” he wrote.

Samour added that, if OBH believed it could not let its providers give testimony about their services, it should “find a qualified outside provider” to do so.

But A.C.’s appeal revealed OBH had not followed that directive. Hood, who authored a dissent, responded that the court should have doubled down on its insistence OBH follow the law, rather than authorizing reassessments as a way to break the logjam.

“Instead of standing by that recent pronouncement, the majority now backpedals,” he wrote.

Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright, writing for himself and Justice Melissa Hart, concurred with Berkenkotter’s majority opinion as a “workaround” to the problematic law, and asked the General Assembly to specifically authorize reevaluations for juveniles. To that effect, an oversight committee in the legislature has already proposed a bill that would expressly allow for second competency evaluations for juveniles in reaction to the B.B.A.M. decision, and would also clarify the information providers may disclose to courts.

The vice chair of the committee, Rep. Adrienne Benavidez, D-Adams County, told Colorado Politics the bill may need further change to address OBH’s alleged conflict of interest.

“OBH is responsible for providing the restoration services. The statute is kind of silent after that as to what happens,” she said.

Jordan Johnson, a spokesperson for OBH’s successor agency, the Office of Civil and Forensic Mental Health, said there is a difference between the professionals who evaluate a juvenile defendant’s competency and those who work to restore competency.

The role of the restoration workers “does NOT include opining on whether or not their clients have been restored to competency,” Johnson wrote in an email. “This could preclude them from being neutral or objective on this topic.”

For Ann Roan, a defense attorney, the inability of judges to receive a full picture of a juvenile defendant’s competency is a piece of the larger problem in Colorado – the shrinking availability of mental health treatment facilities for children.

The Supreme Court, she said, “is just as frustrated by the barriers to getting mental health care for kids who need it as everyone else is.”

The court also recently issued an unrelated juvenile justice decision, ruling on Sept. 26 that juvenile defendants may appeal to a trial judge when a magistrate finds there is probable cause of an offense. That case is People in the Interest of A.S.M.