LIVE UPDATES: Senate tackles fentanyl bill

LATEST: Committee wraps up 11 hours of testimony; amendments Thursday

The Senate Judiciary Committee wrapped up witness testimony just after 1:30 Wednesday morning, but did not take action on the bill nor consider amendments, at the request of the sponsor.

The committee will meet again on Thursday to consider those amendments and vote on the bill. Both sponsors – Sens. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood and John Cooke, R-Greeley, are expected to ask for amendments, as are some of the committee members. Those amendments could deal with another attempt to lower the felony threshold for simple possession to zero, funding for law enforcement investigations into fentanyl overdoses, efforts to repeal the three-year sunset placed on the bill by the House, and others.

The miracle of Narcan

Ryan Christoff of Boulder has faced his own struggles with drugs in his youth, but his story about fentanyl is about his 16-year-old daughter. He found her on her bed, passed out and her lips blue. He started doing chest compressions until help arrived. The EMT gave her four doses of Narcan to revive her. “I witnessed the miracle of Narcan,” he told the committee.

The 19-year-old dealer, a drug user, got into diversion, which is what Christoff wanted. “This bill targets drug users and I’m firmly against that,” and said he came to the hearing to advocate against the lower felony possession threshold.

Christoff said when friends of his daughter come to his house, they leave with Narcan. Why it’s so important is because fentanyl is not like any other drug, he said. When someone goes from respiratory depression to cardiac arrest from heroin is about 90 minutes. With fentanyl, it’s five to 20 minutes.

Senate Judiciary Chair Pete Lee said he recently visited his son, a mental health provider in Philadelphia, and he had Narcan on his dining room table. “Like this?” Christoff asked, holding up a container of Narcan.

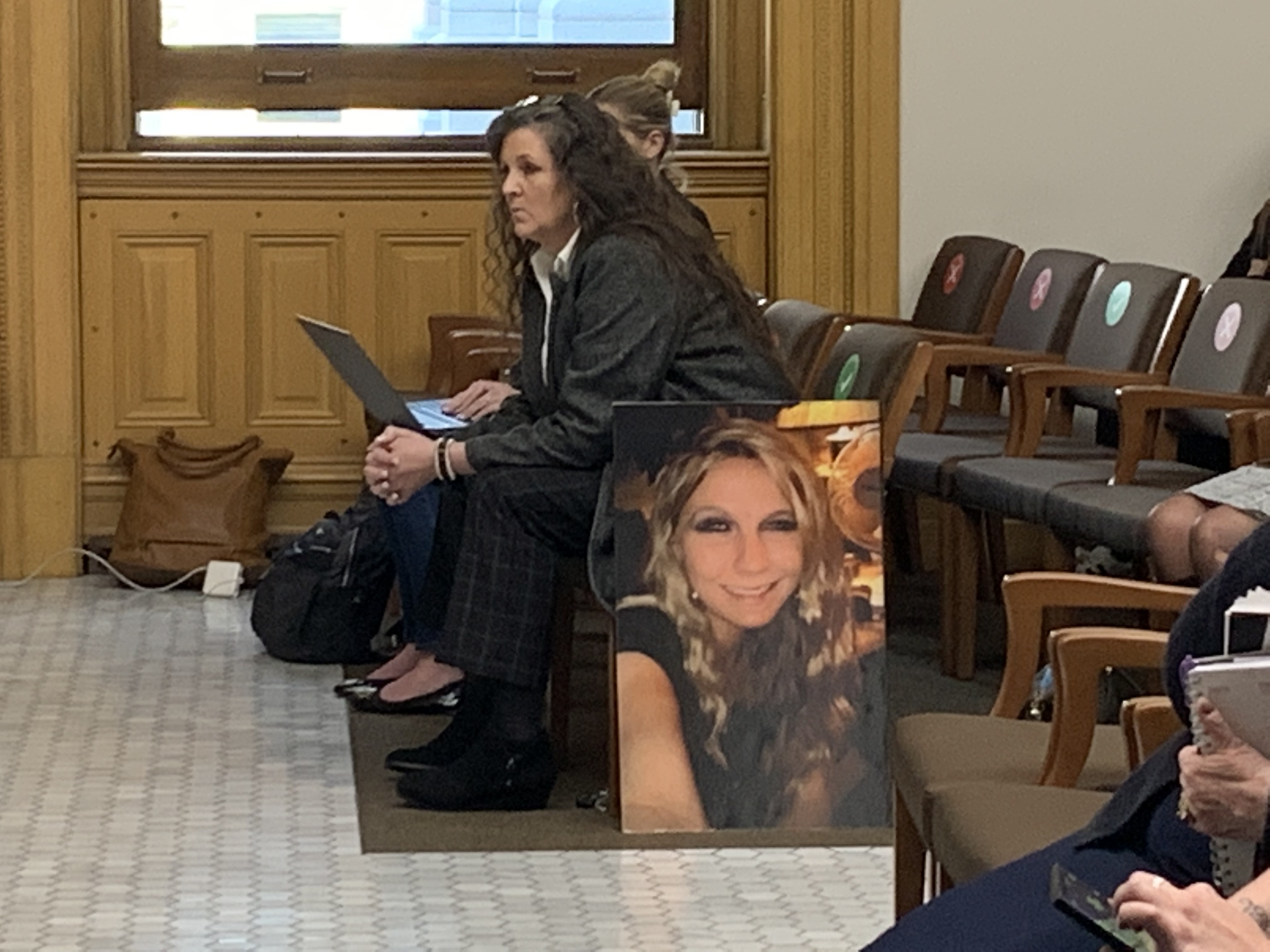

Families tell stories of anguish, argue felony charge is preferable to overdoses

A panel of families who lost adult and teen-aged children to fentanyl overdoses are united in their views that they would rather have their children arrested with felony charges than lose them to overdoses.

Among them: the family of Braden Burks, 24, who died from a fentanyl overdose. His family, including his mother, Tami Gottsegen, said he didn’t know he was taking fentanyl, as the pill he ingested was a counterfeit for a painkiller he had taken for sleeplessness. The high school acquaintance who sold him the pill is now in federal prison.

Families told the committee that law enforcement did not investigate their children’s deaths. In one case, the family turned over a video showing the dealers selling their son the drug, and lamented that, despite their home being declared a crime scene, no investigation took place. They pleaded with lawmakers to fund those investigations.

Harm reduction experts advocate for different solutions

Dr. Josh Barocas, an infectious disease specialist with the CU School of Medicine, said the best scientific evidence does not support what the bill does.

“Criminalizing addiction doesn’t work, mandating treatment doesn’t work. Diseases are never treated by being punitive,” he told committee members.

If law enforcement believes it is the solution, they must be part of the actual solution, he said, pointing to hundreds of overdose deaths in jails and prisons over the last 20 years.

A person who is released from prison is 129 times more likely to die of an overdose than the general public, and fentanyl is in the prisons and jails, he said.

“We must mandate harm reduction, sterile equipment, naloxone and meds for opioid disorders in every jail and prison in the state,” he said. “If an inmate wants meds, it must be given, instead of being left in a cell to detox alone.”

Barocas also recommended that every first responder – whether an EMT, fire department or law enforcement – carry and know how to use naloxone.

“My folks have had testing strips and naloxone since 2013,” said Lisa Raville, executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center based in Denver. All the state is getting from HB 1326 is criminalization and doubling down on the worst ideas, she said, adding, “We won’t be able to arrest our way out of this.”

Raville advocated for conversations about safe usage, as well as setting up overdose prevention sites, a safe supply of drugs and more outreach with teens and middle-schoolers about drugs.

Law enforcement seek change to make possession of fentanyl a felony

A panel of law enforcement officials, along with District Attorney Michael Allen from El Paso County, asked for amendments that everyone’s been expecting: making all simple possession of fentanyl a felony, striking the language on “knowingly” possessing fentanyl, and removing the three-year repeal in the bill.

Sheriff Tyler Brown of Arapahoe County offered another idea: expungement of the felony record, although it’s not a position adopted by all county sheriffs, as well as more money for medically-assisted treatment programs in jails.

This legislation will require all hands on deck, Brown told the committee. “I’m not looking to fill jail cells,” Brown said, “I’m looking for leverage.”

Brown earlier told Colorado Politics he is pushing for a compromise under which possession of any amount of fentanyl would be a felony but also allow for the expungement of the criminal record upon completion of certain programs, such as drug treatment or diversion.

Greg Sadar, deputy chief of the Commerce City Police Department, recounted the Sunday night he got the call that five people were found dead, likely from fentanyl.

The amount taken by the five, Seder said, was 1.8 grams, and a quarter of an ounce was left behind, along with a baby in a crib.

“There is no safe amount of fentanyl to possess,” he said. As to the language on knowing possession of fentanyl, Seder said it is impossible for officers to enforce.

“Knowing” requires a suspect to confess, said Norm Haubert, the interim police chief in Westminster. Haubert also asked for the Good Samaritan language be removed for dealers and distributors, to require mandatory treatment for those arrested, and to repeal the bill’s three-year sunset.

“Any possession is a felony,” Allen told the committee, saying this approach reflects the extreme danger posed by fentanyl. He also said the Good Samaritan language devalues life.

Addiction medicine doctors say criminal penalties’ effects outweigh bill’s benefits

A trio of physicians who work with people use drugs told lawmakers they should focus on treatment, not further incarceration, in response to the fentanyl crisis.

Sarah Rowan said the bill has two sides: One focuses on treatment and harm reduction, and the other targets increasing criminal penalties. The latter, she argued, “is bad for public health” because, among other reasons, incarceration will interrupt treatment. She also noted that many of the people who fatally overdosed in Denver last year were homeless and that felony convictions make it harder to be housed.

Josh Blum, a leading addiction medicine physician, criticized attempts to link a 2019 law change, which made it a misdemeanor – rather than a felony – to possess up to 4 grams of many substances, to the increasing number of fentanyl overdoses in the state.

The trend is happening nationwide, he said.

“To try to make a connection locally that this was the cause when across the entire country, we’ve seen increase in overdose deaths wherever you live, whether it’s urban or rural, doesn’t pass the sniff test,” he said.

He and Stephanie Stewart both said they had patients who used between 30 and 50 pills daily, which translates to 3 grams to 5 grams of fentanyl pills daily.

Cooke asked if the physicians oppose the entire bill or only its criminal penalties.

“We’re in support of harm reduction,” Rowan replied. “We’re in support of more Naloxone. … We need much more treatment, as my colleagues have said. So, we are worried that the harms from more legal problems for our patients will outweigh the benefit of this bill.”

Cooke asked if the $33 million of funding that the bill would allocate, including $20 million for more Naloxone, isn’t enough.

“There’s a lot of great stuff in this bill that we wholeheartedly support, including expanding access to treatment and treatment and assessment in corrections facilities,” Blum replied.

Gonzales presses district attorneys on racial disparities in criminal justice system

Gonzales also queried the district attorneys about racial disparities in the justice system and whether the bill will drive more of that in the next three to four years if possession of small amounts of fentanyl becomes a felony.

That question also hints at a concern quietly raised by Democrats – that putting felony charges on possession of less than 4 grams of fentanyl will result in undocumented immigrants being arrested and a felony charge is the difference between staying in the United States or being deported. A misdemeanor charge doesn’t raise that issue.

Brian Mason, the Adams County district attorney, acknowledged Gonzales’ concerns and agreed there are racial disparities. But there’s no way to know what will happen in the next three to four years, he responded.

Attorney General Phil Weiser said he is committed to not seeing that kind of effect from HB 1326.

Polis presses for “harsher criminal penalties” for fentanyl possession

Gov. Jared Polis told Colorado Politics through a spokesperson that the opioid crisis “demands a robust,” multipronged response. The governor also reiterated his position that because fentanyl is “extremely deadly,” it should be met with “tougher penalties” for possession.

Here’s the full statement from the Governor’s Office: “The bill is still making its way through the process and the Governor is confident Republicans and Democrats will pass a bill that can save lives and help get fentanyl off of our streets. This challenge demands a robust public health approach that will address the root causes, educate the public, get deadly fentanyl dealers off the streets, and keep people alive. Fentanyl is extremely deadly and Governor Polis continues to support tougher penalties for possession which he called for in his state of the state address and continues to urge the legislature to get a comprehensive bill to his desk addressing this crisis, including making testing strips more available, increasing drug addiction treatment, and harsher criminal penalties for possessions and especially for dealing. He has said the science and data around each drug has to be examined to come up with the appropriate public policy framework that promotes public safety.”

Prosecutors urge panel to remove “know” or “should have known” language

The first panel to give testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee included Attorney General Phil Weiser and three district attorneys who have been vocal about the bill and the need for changes to the state’s fentanyl laws.

They asked legislators to make several amendments to the bill. Weiser said every jail in the state should be required to offer medication-assisted treatment, which uses methadone and similar medicines to treat opioid addiction. Right now, jails must have a policy on MAT but aren’t required to offer it. Weiser also referenced an amendment made by the House Judiciary Committee, which would make it a felony to possess any amount of a substance that’s at least 60% of fentanyl. But that would only take effect once state law enforcement gains the ability to do that level of testing.

The district attorneys who testified with Weiser – Denver’s Beth McCann, Boulder’s Michael Dougherty and Adams and Broomfield counties’ Brian Mason – all said they aren’t able to do that testing currently.

Those same district attorneys also asked lawmakers to remove another addition made in the House. While the bill as written says that possessing more than a gram of a substance containing fentanyl is a felony, it would also require that the person caught with that substance knew or should’ve known that it contained the drug. It’s an attempt to address fentanyl’s presence in many other drugs, often without the knowledge of the person who bought that drug.

Mason and Dougherty both said know-or-should’ve-known language would make it “impossible” for prosecutors to actually charge the new felony. The language comes from “good intentions,” Dougherty said, but it makes the new felony itself “unworkable,” absent “a confession or something similar.”

Sen. Pete Lee, the committee’s chairman, noted that fentanyl is increasingly prevalent in other substances – from meth to heroin to cocaine – and that many users of those substances don’t know that fentanyl’s mixed into what they just bought. Without the knew-or-should’ve-known language, he said, those people would be caught up in the “draconian” laws proposed in this fentanyl bill.

Gonzales sets the stage for the discussion

Senate Judiciary Vice-Chair Julie Gonzales, D-Denver, who is expected to ask pointed questions during Tuesday’s hearing, started off with a question that produced a divided response from the sponsors, Sens. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood, and Sen. John Cooke, R-Greeley.

Gonzales asked whether people who are in addiction should be treated in a retributive manner or rehabilitative manner.

“It’s a little of both, not one or the other,” Cooke replied.

The state has put a lot of money into rehabilitation, and HB 1326 will put in another $32.3 million, he said, adding, “We need to work with the people who are addicted, but at some point personal responsibility” has to come into play.

Cooke said for the first arrest on a low-level felony, the defendant goes into diversion, and the first charge doesn’t even go into the record. But as a person is arrested multiple times, Cooke said, incarceration becomes a tool to force treatment. The criminal justice system will do what it has to in order to make someone stop using drugs, he said.

Pettersen, whose family history includes a mom who was once addicted to opioids, responded that addiction is a disease.

“It takes professional medical help to get people to a place where they can live in recovery and thrive again,” she said.

But state policy has failed, she said. While the state has invested in residential treatment and other programs, 400 people are on waiting lists for those services. That’s unacceptable and a policy failure, she said.

Gonzales also pointed out the conversation around fentanyl has been driven by emotion, fear and anger, and hinted that some of it may be based on where the drugs are coming from: China, Mexico and India, which is an emerging source.

She asked Cooke his source for data on how law enforcement determines where the fentanyl is coming from.

It’s from the Drug Enforcement Administration, which works with the Mexican government, he replied. The DEA does intensive investigations, including seizing drugs coming across the border. An officer on the street might not be able to look at a pill and know it came from Mexico, but the DEA, FBI and even local law enforcement at the borders see how much is seized, Cooke said.

A bipartisan Congressional committee, which published its extensive findings on fentanyl in February, also found that China is the primary source of the chemicals needed to make the drug; that those ingredients are shipped to Mexico; and, that Mexican drug-trafficking organizations then synthesize those chemicals into fentanyl and then ship the drug into the United States.

For a time, fentanyl was being shipped in large numbers directly from China to the United States. But that changed several years ago, when the Chinese government cracked down on fentanyl and its analogues. After that, chemicals were re-routed increasingly to Mexican cartels.

LATEST: Pettersen says she’s working on medication-assisted treatment amendment

2:40 p.m.: In her opening remarks, Sen. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood, the bill’s Senate co-sponsor, hinted at, but didn’t describe, an amendment she’s working on related to medication-assisted treatment in jails. MAT, as its known, involves using prescriptions, such as methadone or buprenorphine, to curb cravings and avoid withdrawals in people who use illicit opioids.

Right now, the bill would require jails that receive certain state funding to have “protocols” related to MAT, but it doesn’t require they actually offer the program. Experts say that’s similar to what’s in state law, which requires county jails have a policy on MAT without a mandate that they provide it.

Experts and advocates say MAT – generally but particularly in correctional facilities – is key to fighting the opioid epidemic. People recently released from incarceration are significantly more likely – somewhere between 40 times and 129 times, depending on the study – to fatally overdose than the general population.

Sheriffs told the Gazette and Colorado Politics last month that, if the legislature is going to require MAT in jails, then lawmakers should provide money to counties to support it.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

Attorney General Phil Weiser will testify on House Bill 1326

Seen in the room are Attorney General Phil Weiser, district attorneys from several jurisdictions and advocates from the harm reduction community. Weiser, who supports making it a felony to possess any amount of fentanyl, will likely testify.

About 65 people have signed up to testify, both in person and online.

Senate Judiciary Committee to hear fentanyl bill at 2 p.m.

Sen. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood, the bill’s Senate co-sponsor, told Colorado Politics the Judiciary Committee will only hear witness testimony today and tackle amendments when the panel meets on Thursday.

The panel will likely hear testimony from advocates on both the criminal justice side and the harm reduction side and family members of those who died from fentanyl overdoses.

And just like in the House, the discussion will likely revolve around how to treat simple possession of fentanyl and whether to make it a felony to possess any amount of the deadly drug. However, the committee will take witness testimony only, with action on amendments and a committee vote on Thursday.

As introduced, House Bill 1326 ramps up criminal penalties for distribution of fentanyl, including a felony 1 drug charge for distribution that results in death. It also sets up a “Good Samaritan” clause, allowing a person who provides fentanyl to someone who overdoses – whether intentional or not – to face a lesser than a felony 1 drug charge, even if a recipient dies, if the person calls 911, stays on scene and cooperates with first responders or law enforcement.

A 2019 law made possession of up to 4 grams of fentanyl a misdemeanor, but, as amended in the House, HB 1326 lowers that felony threshold to 1 gram.

There’s some nuance here: Experts and law enforcement have said that fentanyl pills typically weigh one-tenth of a gram each. The bulk of that weight isn’t fentanyl; as Denver District Attorney Beth McCann put it, they’re mostly a “filler” substance used by drug traffickers to form most of the pill and keep its shape. Sometimes that filler is acetaminophen, essentially Tylenol, and sometimes it’s an over-the-counter supplement you could get at GNC.

The actual amount of fentanyl in each of those pills varies: According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, some pills may have no fentanyl; some may have half a milligram. On the higher end, they may contain 5 milligrams of fentanyl – significantly more than what’s considered a lethal dose for the average person. But an increasing amount of these pills – 42%, according to recent seizures by the DEA – have enough fentanyl to be deadly.

As written, the bill would make it a felony to possess more than 1 gram of a substance containing fentanyl. So 11 pills, weighing one-tenth of a gram each, would qualify, even if those pills have far less than 1 gram of actual fentanyl in them.

The bill allocates $20 million to pay for more opioid overdose antidotes, such as Naloxone, $6 million to expand the state’s harm-reduction grant program this year, and $3 million to help jails develop new withdrawal treatment protocols. Correctional facilities would be required to offer opioid agonists and antagonists – methadone, for example – to inmates with opioid-use disorders. And if it’s medically necessary, treatment for that inmate will continue throughout their incarceration under the legislation.

The bill also includes an education program to inform users that fentanyl can be found in any illicit street drug, including heroin, methadone or cocaine, or mixed with analgesics, such as acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, for example. The drug can also be formed to imitate other drugs, such as Percocet or Xanax. The bill contains harsher penalties for dealers and those who import pure fentanyl into the state.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com