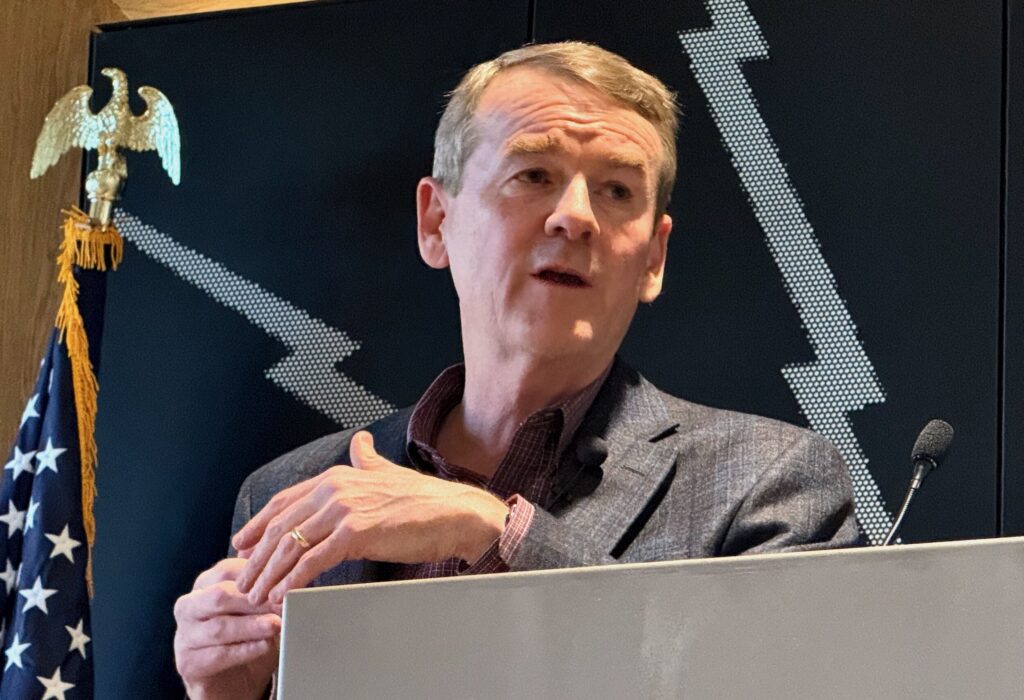

Garnett’s gambit: House speaker fights for legacy-defining fentanyl bill in final year as legislator

When House Speaker Alec Garnett sat down with Colorado Politics in January to reflect on his last year in office, he said he always prefers taking on “one tough one than a bunch of consensus-driven ideas.”

“I always tell Emily that I’m going to focus on one big thing,” said Garnett, one of the youngest to serve as House speaker in the Colorado General Assembly. Emily, an attorney, is Garnett’s wife. “Sometimes I don’t know [what it will be], but it always seems to find me.”

That one, big, tough thing, indeed, found Garnett yet again.

The Denver Democrat, who is in his fourth and final term in the House, is shepherding the passage of one the toughest bills to emerge out of the legislature this year – a sweeping measure that hopes to counteract fentanyl’s deadly wake in the state.

The measure, if ultimately enacted into law, will help shape the speaker’s legacy as public servant and leader in an era of Democratic dominance, under which Garnett, Gov. Jared Polis and their allies in state government ushered in progressive ideals, notably in the area of criminal justice.

“Garnett has presided ably over a House with a huge Democratic lean and an expansive agenda. He has tapped the brakes on occasion and the accelerator at other times depending on the issue,” said Eric Sondermann, who regularly writes columns for Colorado Politics and the Gazette newspapers. “Together with Gov. Polis and Senate President (Steve) Fenberg, they certainly constitute a new, younger generation of political leadership at the Capitol and a more progressive philosophy.”

And if Garnett decides to run for mayor of Denver – his name is among a few being tossed around as possible contenders, though he shut down the idea for now, at least – many say his work on fentanyl and public perception on crime will be a factor in the race.

“I do think that fentanyl – and public safety more broadly – will impact Denver’s mayoral race,” said Michael Fields, president of the conservative-leaning think tank Advance Colorado Institute. “Denver is a tipping point right now. Downtown has changed, housing costs are skyrocketing, crime is up, and businesses are looking elsewhere. The next leader of the city is going to need to be strong, and be able to unite people to fix these problems.”

Sondermann, who also describes Denver as facing a fork in the road, acknowledged the nimble balancing act that Garnett finds himself in.

“The fentanyl issue is a particularly vexing one,” Sondermann said. “It is acknowledged in most circles that Democratic legislators overstepped in their so-called reform a couple of years ago. Garnett is now center-stage in trying to craft and shepherd through an adjustment that is palatable to both the anti-criminalization elements of his party and those far more concerned with growing lawlessness.”

He added: “That is not an easy balance to achieve.”

Like many, Sondermann sees fentanyl and its malevolent tally of dead and sickened Coloradans as inevitably occupying “front and center” in next year’s mayor’s race in the state’s most populous city, and candidates hoping to court Denver’s progressive voting bloc will “also have to walk that line.”

“The trick is that the decriminalization agenda is at odds with the lived experience of an increasing number of voters, even in left-leaning Denver. That is something for which Rep. Leslie Herod, a likely mayoral candidate and sponsor of the earlier reform bill, will have to answer, along with Garnett, if he ends up entering the race.”

Herod, interestingly, grilled law enforcement officials, notably Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen, during the committee hearing on the bill in an exchange that offered a glimpse into the relationship between the city’s police chief and its representative at the Capitol, who could also jump into the mayor’s race.

The immediate battle ahead

For now, the battle in front of Garnett is getting the fentanyl bill out of the legislature and onto the governor’s desk.

As one of the bill’s sponsors, the Denver Democrat stands right in the middle of the crossfire, caught not just between law enforcement advocates and criminal justice advocates, but also among competing views within his caucus. All the parties agree the fentanyl crisis needs a unified state response, but they diverge on how to treat simple possession of fentanyl.

In the last few days, Garnett has tried to steer the conversation toward what he thinks is the most essential element of the fentanyl legislation – its multi-pronged approach to combating the drug – instead of the incessant focus on fentanyl possession.

During the April 13 House Judiciary hearing, Garnett acknowledged the bill isn’t perfect but lamented that not enough attention has been paid to its provisions on harm reduction and education. All told, he said, the measure is a “monumental step forward.”

The debate over possession revolves around two interlocking issues: The first dwells on a 2019 law that made it a misdemeanor to possess up to 4 grams of many drugs, including fentanyl. The second deals with fentanyl’s unique nature. A potent synthetic opioid used legitimately in medicine, the substance is mixed illicitly into other drugs, such as meth and cocaine, and is primarily found in pills often made to look like legitimate oxycodone tablets. Those pills are rarely pure fentanyl, officials in Colorado and elsewhere have said. Often, they have relatively low amounts of fentanyl and are primarily composed of other substances, such as the active ingredient in Tylenol. Still, because fentanyl is so potent at low doses, the pills are deadly.

Law enforcement groups, some mayors – Denver’s Michael Hancock, among them – and families whose loved ones have overdosed stand on one side of that debate, urging policymakers to lower the felony threshold for its possession to any amount. On the other side are health providers and addiction experts, who insist that legislators adopt a health-centric approach to confront Colorado’s opioid crisis.

And in an effort to accommodate the diametrically opposed factions, Garnett offered to set the threshold for felony possession at 1 gram, which is about 10 pills, an amount that a person with addiction problems could go through in a day or less, due to fentanyl’s quick but short-lived high.

Neither side appears happy with the speaker’s solution.

The harm reduction activists argue that any step toward “felonization” returns Colorado back to the failed policies of the “War on Drugs,” while the law enforcement advocates insist 1 gram still still leaves too many Coloradans dead.

The coalition behind the bill has managed to get it out of the House committee and through hours-long debate in the House on April 22. A full House vote is scheduled for April 25.

Fields of Advance Colorado acknowledged the difficulty that Garnett faces.

“There is no doubt that Speaker Garnett has tried to find a compromise on it, but it’s one of those bills where nobody will end up happy,” Fields said. “The far-left doesn’t want any possession to be a felony. But most Coloradans see fentanyl for what it is – a poison that is killing two Coloradans a day, including kids. Given this, any possession of fentanyl should be a felony.”

The generalist

A veteran of some of the most monumental fights at the state Capitol, the House speaker has taken on construction defects, “red flag” legislation, sports betting and transportation funding – just to name a few – in his four terms as a legislator.

But his biggest test came two years ago, when a shapeshifting virus began to infect, sicken and kill millions of people around the world, forcing governments to impose drastic measures and sending economies into a nosedive.

Rep. Kerry Tipper, D-Lakewood, put the enormity of Garnett’s challenge this way: “He stepped in to this position as speaker of the House two months before the entire world turned up side down.”

Digging the state out of the COVID-induced hole would have already been a herculean task, according to Tipper, who, at the time, thought the pandemic would define the speaker’s legacy.

But even amidst the health crisis, Garnett shaped and shepherded some of the most profound measures to emerge out of the state Capitol in decades. Tipper said they included, for example, last year’s transportation bill, which created hundreds of millions of dollars in new revenue streams top pay for infrastructure projects.

“When I think of Alec, I think of him as this generalist,” Tipper said.

His expertise, she said, lies not necessarily with any particularly subject but in navigating the complexities of policymaking and getting something through.

America’s grand experiment in representative democracy was purposely designed to slow or even kill legislation, a way of forcing parties to come to a compromise to ensure a new law doesn’t enter society as a knife that wounds but as a nourishment – or at least not a shock that sends society reeling. Tipper said Garnett has become an astute student of the art of legislating – the leader who sees the big picture, reaches consensus and finds a way to get a proposal to the finish line.

It’s that experience, she said, that makes Garnett the perfect – and perhaps only – legislator to take on an issue as complex and as emotionally draining as the fentanyl legislation.

“I don’t know anybody else honestly in the building that could be doing this bill and get something across the line successfully,” Tipper said, adding that’s probably why Garnett decided to take on the fentanyl bill.

Garnett hinted as much in an interview with Colorado Politics.

“I approach things differently than most legislators,” he said. “There’s an art to the public policy process and to do the best you can to help move forward solutions to the problems Colorado encounters.”

He added: “I’ve tried to take on big issues that, if they were left to one side or the other, could become either highly politicized or couldn’t move forward with the best solutions possible.”

A future behind the scenes?

The third Democrat from the Capitol Hill House District to wield the speaker’s gavel, Garnett’s political future is wide open.

For now, he dismisses the idea of running for any other elected office. Pointing out that his hair is now grayer and he’s earned a few wrinkles, Garnett said he has poured his heart and soul into each issue he has tackled, and noted that this kind of undertaking – intensive, relentless, grinding – is challenging to do forever.

“I believe public service is meant to be temporary,” he said. “It’s meant to bring people in who are citizens to do the best they can.”

But that doesn’t mean he is done with politics. Garnett hinted of remaining in the public policy arena, where he has spent his entire career in, but behind the scenes, perhaps a little away from the limelight.

“I’m proud of my ability to solve problems and bring people together,” he said. “I can use the skills I have and not necessarily be in an elected office.”

But it’s precisely those skills, his relative youth and what has been a successful run as a policymaker – his detractors argue that the policies he embraced moved Colorado in the wrong direction but readily agree he succeeded in pursuing a progressive agenda – that put him on the radar for another office, notably the mayor’s chair in Denver.

Garnett said there are collateral consequences for launching a full-blown campaign for the seat, the big one being family. During his eight years at the Capitol, he and Emily have brought three children into the world. There have been days when he had ducked out during a debate to make quesadillas for the kids – because they like how their dad does it – or tucked them into bed. It helps that he lives less than a mile from the Capitol.

“I’ve always tried to put family first,” Garnett said. “In this moment in time, it would be very challenging for me to be the mayor Denver needs – very hands on, who can solve a lot of problems” and raise his three kids the way he ought to.

If or when – observers say it’s only a matter of time – he seeks another office, he will run on his legislative record as a House member and his decisions as a speaker.

His Democratic allies hails the work they accomplished with Garnett at the helm.

“Under the leadership of my friend Speaker Garnett,” House Majority Leader Daneya Esgar told Colorado Politics, “the House has passed historic legislation to drive down the cost of health insurance, save people money on their prescription drugs, fix our broken transportation funding system, and enact universal preschool for all four-year-olds in our state.”

“Working together, the Speaker and I led the House through a global pandemic that saw us pass a $1 billion state stimulus plan and direct billions in federal funds toward the most pressing issues in our communities – access to affordable housing, behavioral health, and skills training that advances careers. There’s no question about the speaker’s legacy in the Capitol,” Esgar said.

Fields, the political strategist, also frames Garnett’s legacy against the backdrop of Democrats’ electoral wins that put them in charge of all levers of state government.

“I don’t believe Colorado is better off than it was four years ago. Single-party rule and bad policies have made our state less safe and more expensive. That’s not one person’s fault – it’s a combination of Democrats in the Senate, House, and governor’s mansion,” Fields said, calling, for one, the 2019 law that made less than 4 grams of fentanyl a misdemeanor “one of the worst pieces of legislation passed in the last few decades.”

Mitch Morrissey, the former district attorney for Denver who met a young Alec Garnett years ago – Garnett’s father, Stan, served as Boulder district attorney, said in viewing the speaker’s tenure through the lens of criminal justice, he is disappointed Garnett “ignored the vital importance of confronting the surge in crime in Colorado.”

“As Speaker, Garnett missed a leadership opportunity to call for a comprehensive review of the crime wave and the unintended consequences and higher costs of the crime policies that were put in place in Colorado before and during his time in the legislature,” Morrissey said.

State policymakers identify soaring criminality in Colorado as a key challenge they vow tackle this year. Some blame the state’s “criminal friendly” policies as contributing to the trend, while others say the “lock up everybody” mentality has a longer record of failing communities. Colorado Politics Managing Editor Luige Del Puerto leads a panel of experts to discuss crime in the state, and what can be done about it. Panelists: ? Lisa Pasko, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Sociology and Criminology, Universit (lisa.pasko@du.edu) ? Paul Pazen, Chief, Denver Police Department (Paul.pazen@denvergov.org) ? Mitch Morrissey, Criminal Justice Fellow, Common Sense Institute (mitch.r.morrissey@gmail.com) ? Lisa Raville, Executive Director, Harm Reduction Action Center (lisa.harm.reduction@gmail.com)

What political observers agree is the breadth of Garnett’s legacy. Tipper, the Lakewood Democrat, puts it this way after noting how the speaker has led Colorado through the pandemic, shepherded “transformational” legislation during his tenure and greatly expanded his caucus: “His legacy is so much bigger than this one bill.”

“If this is going to be the issue that defines me,” Garnett said, “I’m willing to accept that because I think that no state has gone from zero to four and tried to bridge their way back.”