Like Colorado, other states scramble to confront fentanyl’s deadly wake in America

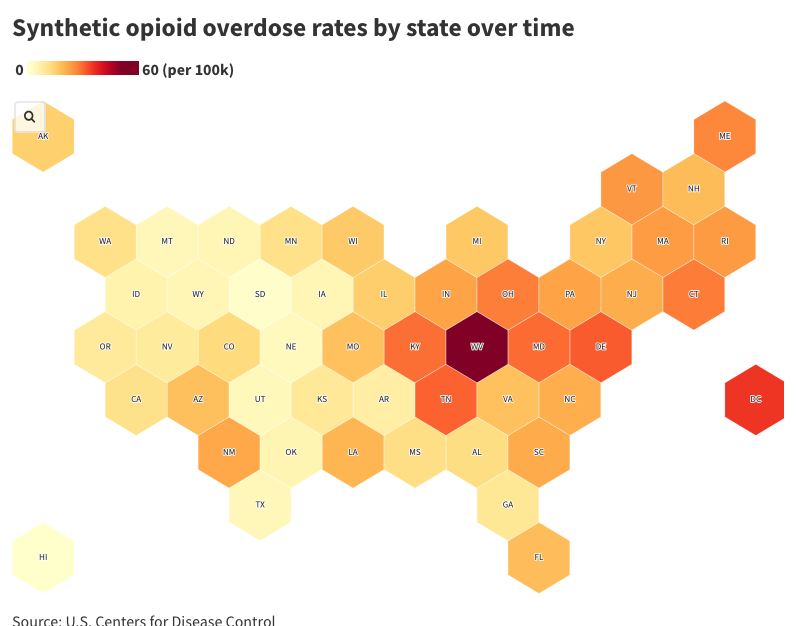

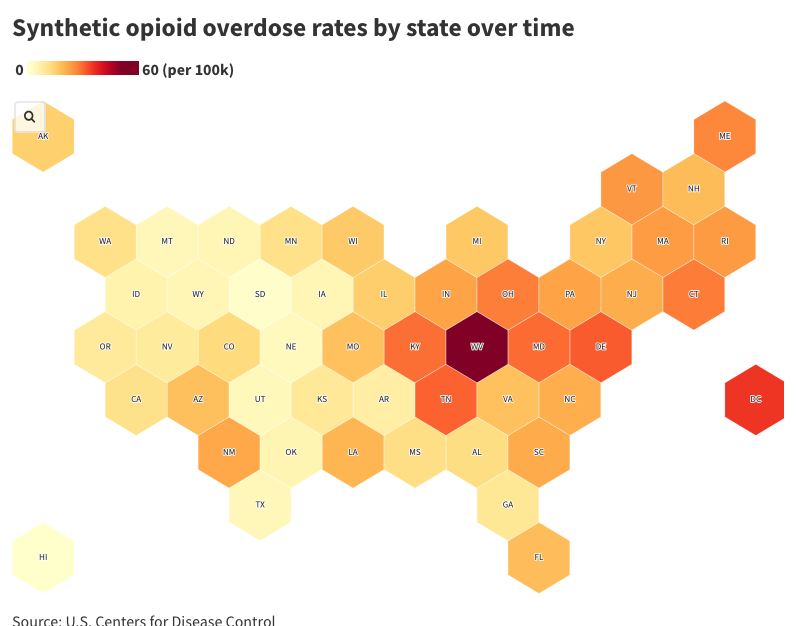

Colorado is one of many states looking for answers to the deadly fentanyl crisis as overdoses hit an all-time high and experts point to national data showing the synthetic opioid has claimed a bigger and bigger share of those cases.

The responses around the country offer a glimpse of the complexity of the fentanyl response and echo the debate that occupied Colorado’s legislature last week between adding public health measures to reduce the risk to users and increasing the penalties for dealing fentanyl or mixing it with other drugs.

The National Conference of State Legislatures found nine states with fentanyl-specific drug trafficking or possession laws as of last year: Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, West Virginia and North and South Dakota.

Similar measures have been introduced or considered since the start of 2021 in at least 19 states, the Associated Press found in an analysis of bills compiled by LegiScan. That does not include measures to add more synthetic opioids to controlled substance lists to mirror federal law, the AP wrote. Those have been adopted in many states, with bipartisan support.

Colorado’s fentanyl crisis: Full coverage

States, such as California, are weighing harsher penalties for possessing or distributing fentanyl. In California, lawmakers are considering a measure to make it a felony to possess more than 2 grams of a substance containing fentanyl.

Increasingly, states have turned their attention to fentanyl and its derivatives, targeting its delivery or possession. Maine, for example, makes it a trafficking offense to possess 2 or more grams of fentanyl powder. Massachusetts specifically prohibits the drug’s trafficking.

West Virginia, which is among the worst-hit states, prohibits the manufacture, delivery, transport into the state and possession of fentanyl, under which less than 1 gram of the drug means up to 10 years in prison.

Colorado House committee advances bill that lowers felony threshold for fentanyl possession

Others states are focusing more on public health measures, such as considering increasing access to Naloxone and test strips to limiting legitimate opioid prescriptions and collecting more data on overdoses. Since last year, at least a half-dozen states have enacted similar laws and at least a dozen others have considered them, according to research by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Tennessee and New Mexico legalized test strips earlier this year (some states had considered the strips to be paraphernalia), according to an article in MedPage Today. A number of other states are either currently considering a similar move or have already done so, a Gazette analysis showed. In all, more than 30 states have passed, voted down or are considering legislation related to fentanyl test strips.

Delaware and Tennessee, among many others, have also passed laws recently broadening who can distribute Naloxone.

On the more cutting edge, New York City opened the nation’s first safe-use site, where people can use illicit substances under the watch of providers. According to NBC New York, the site reversed “more than 150 overdoses during about 9,500 visits” in its first three months.

In February, the Department of Justice indicated it would be open to allowing the sites.

In Colorado, a bipartisan group of lawmakers last week tackled a bill, which is also backed by Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, that would increase penalties for dealers possessing only 1 gram of fentanyl and in cases where the drug leads to a death. The legislation also would increase the accessibility of naloxone and test strips, while steering people who possess fentanyl into education and treatment programs.

A line has been drawn in the sand in Colorado, with the opposing sides proposing diametrically divergent approaches to criminalization: Law enforcement advocates focus on fentanyl’s grim death toll, insisting criminal possession is the only way to stop it, while harm reduction experts argue “felonization” merely returns Colorado to the War on Drugs, a strategy that already failed with catastrophic social costs.

Colorado Conversation on April 20: Tackling the fentanyl crisis

Law enforcement and some families pressed lawmakers to lower the felony threshold for possession of fentanyl – currently set at 4 grams – to any amount, while medical providers and addiction experts urged the committee to leave the issue alone and to reconsider other criminal penalties in the bill. They advocated, as they had before the bill was even released, that legislators adopt a health-centric approach to confront Colorado’s opioid crisis.

When the committee voted 24 hours after Tuesday’s hearing began to send the bill to the House Appropriations Committee, the legislation had been amended most notably to set the felony threshold for possession at 1 gram.

The criminal justice approach “becomes the baseline, the default, and people are arguing against that,” instead of “we’re going to follow the evidence, and we’re going to do these things that the evidence shows is likely to work,” said Corey Davis, a deputy director with the Network for Public Health Law.

Davis and others, including three Denver physicians who testified in front of the judiciary committee on Tuesday, repeatedly said law enforcement should provide evidence that more incarceration will address the crisis.

There is evidence, they said, for increasing access to Naloxone and other harm reduction efforts, and for improving access to medication-assisted and outpatient treatments.

Noa Krawczyk of the New York University’s Department of Population Health and School of Medicine called that treatment modality “the gold standard,” and she said increasing its availability should be states’ priority.

Rob Valuck, head of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention, previously said that Colorado currently has capacity to meet just one-third of its substance-abuse treatment need.

James Karbach, a Colorado public defender and the office’s director of legislative policy and external communications, told the House Judiciary Committee he had compared drug penalties against overdose rates nationwide and found no correlation.

“I continue to believe the criminal laws and overdose data, along with years of research, is best characterized as showing that there is no evidence that felony possession laws reduce overdose deaths or illegal drug use,” he told the Gazette in a subsequent email.

But law enforcement advocates, backed by city officials, argue that fentanyl presents a unique, and too often deadly, challenge.

The synthetic opioid can be lethal in small doses, they point out, noting it is involved in the deaths of nearly 900 Coloradans in 2021 – up from 41 in 2015 and quadruple the number from 2019.

Though pills made to look like oxycodone are how fentanyl is typically seen in Colorado, drug traffickers have increasingly begun mixing it into other substances, unbeknownst to users, with often fatal consequences.

They insist that anything less than the toughest sanction on possession will fail to stop fentanyl’s trail of death.

While law enforcement argue that trend is further reason to have zero tolerance for distributors and fentanyl generally, opponents counter that because fentanyl is increasingly ever-present across many types of drugs, “felonizing” any amount of its possession in any mixture would lead to a de facto crackdown on all drugs and further incarcerate users of all stripes.

Police, some mayors, district attorneys and Attorney General Phil Weiser have all said that fentanyl is so potent that possessing all but the smallest amounts should be indicative of an intent to distribute and, thus, a direct danger to users and the public.

Because of shifts in the drug supply, which has made heroin less available and fentanyl far more ubiquitous, many people with opioid-use disorders are left with fentanyl as the only way to satisfy their dependency and avoid agonizing drug withdrawals.

Some in law enforcement have argued that incarcerating users is the best, and in some parts of the state only, way to get them treatment before they fatally overdose. The legislation would require courts to order residential treatment as a condition of probation for people convicted under the bill’s new fentanyl possession and distribution levels. The law enforcement coalition praised that addition. Krawczyk, the NYU School of Medicine professor, said it isn’t “totally unreasonable” to require treatment.

She and Davis pointed to studies that show people recently released from correctional facilities are at significantly higher risk of fatally overdosing than the general population. A 2018 study by researchers at the University of North Carolina put the risk at 40 times higher.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.