Colorado lawmakers poised to introduce legislation tackling fentanyl crisis

State lawmakers are nearing completion on a comprehensive draft bill aimed at confronting the state’s growing fentanyl crisis by increasing the penalty for peddling the deadly drug but not reversing a 2019 law that critics blame for exacerbating Colorado’s opioid tragedy.

Possession of less than 4 grams of fentanyl is still a misdemeanor under the legislation, a draft of which was obtained by Colorado Politics.

However, under the draft, any possession of fentanyl with an intent to distribute, no matter how much, is a minimum class two drug felony. That charge can result in a two to four years in prison, plus fines of $2,000 to $500,000. The charge comes with an sentence enhancement that can add an additional two years.

The draft broadly outlines both how the bill’s sponsors will deal with the criminal justice side of the issue and help those drawn into the world of addiction, touting it as a life-saving measure that comprehensively takes into account the complexity of the crisis.

“This is about saving lives,” Speaker of the House Alec Garnett, D-Denver, said.

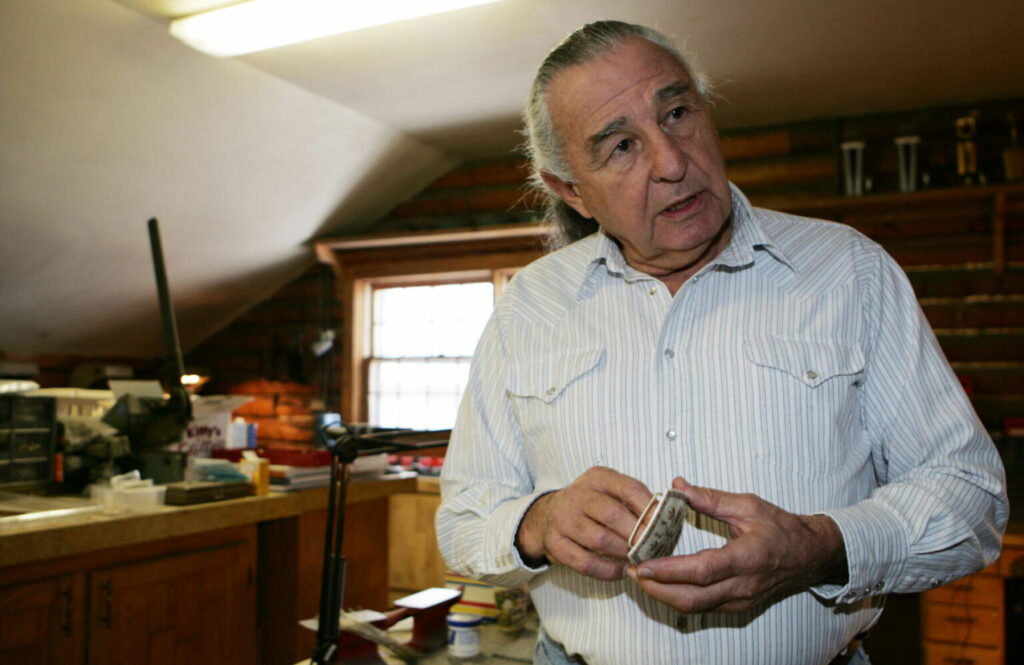

In an interview with Colorado Politics, Gov. Jared Polis pointed to the increased availability of testing strips and kits to law enforcement under the proposal and said it means rather than tracing a trail of dead bodies to hold someone responsible for distribution, “you’ll be able to detect earlier in the process,” and law enforcement will be able to investigate and find patterns.

This will be a tool in the field – not in the lab – that will allow faster tracking back to the drug’s source, said Polis, who called for increasing the penalty for peddling fentanyl during his State of the State address before the Colorado General Assembly in January.

Others criticized the proposal’s approach.

Though Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen commended lawmakers for “attempting” to fix the problem, he said the law governing simple possession needs to be changed and that he doesn’t know what could justify allowing possession of up to 4 grams of fentanyl to remain a misdemeanor.

“There is no safe amount of fentanyl on our streets,” he said in an interview Wednesday afternoon, noting that, on average, more than one person dies from a drug overdose in Denver every day. “And we are hopeful that this possession side can be addressed, just based on the level of harm that fentanyl has created.”

In addition to Garnett, other sponsors expected are Rep. Mike Lynch, R-Wellington; and, Sens. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood and John Cooke, R-Greeley.* The bill is likely to be introduced by the end of this week, according to sources, but since it’s a House bill, it’s unlikely to see its first committee action until after the chamber has dealt with the 2022-23 state budget, also known as the Long Appropriations Budget, which is slated for introduction and action beginning Monday.

The fentanyl legislation comes amid heightened attention to the drug’s increasingly deadly impact in Colorado. Fatal overdoses involving the drug have skyrocketed since 2015, the product of shifting economics and priorities within the illicit drug trade and accelerated by the pandemic. More than 800 Coloradans died after ingesting fentanyl in 2021, according to state data. That represents a roughly 50% increase from 2020 and more than triple the number of deaths from 2019.

Criminal justice

One of the biggest complaints on how the state legislature has handled fentanyl is tied to a bipartisan 2019 law that decriminalized possession of certain Schedule II drugs, such as heroin and fentanyl. The 2019 legislation allowed for misdemeanor charges for possession of less than 4 grams, but critics say that turned out to be a boon for drug dealers, who learned to carry 39 fentanyl pills of 0.1 gram each, enough to sell but not enough for the more serious felony charge.

The state went from 147 deaths in 2019 to 709 in 2021, a 382% increase, according to state Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Brighton, who had hoped to bring her own bill on the issue but was denied permission to introduce a late bill.

Fatal fentanyl overdoses have been rising in Colorado and nationally for years, a trend that began before the 2019 law change, state and national data show.

Last week, the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition published a letter to lawmakers signed by more than 60 organizations arguing that the crisis has not been caused or worsened by the the legislature’s action in 2019.

Despite those organizations’ arguments, law enforcements officials and some lawmakers, who argue otherwise, have called for a reversal of that 2019 bill.

The draft bill, stamped March 18, doesn’t reverse the 2019 law.

But, as noted above, lawmakers are seeking harsher penalties for the intent to distribute fentanyl.

Also, possession of 2 to 4 grams of fentanyl is a class two drug felony, which carries a sentence of four to eight years in prison, plus fines of $3,000 to $750,000.00. Aggravating circumstances makes the prison term eight to 16 years.

Under the draft, the most serious of felonies, class 1, is applied to those who distribute large quantities of fentanyl. Dealers found with more than 50 grams could face a class 1 drug charge, which carries a mandatory eight to 32 years in prison, plus fines of $5,000 to $1 million. There is a minimum prison term of 12 years if there are aggravating circumstances.

A person who distributes any quantity of fentanyl that results in death gets the same level one charge but without the mandatory minimum sentence, according to the draft.

However, if the dealer has less than 4 grams of fentanyl and follows “good Samaritan guidelines,” which would require the dealer to call 911 for an overdose, that dealer would face la lesser charge, a 3rd or 4th level felony, according to Herod, who explained the Good Samaritan provision is intended to address users, not dealers.

Those who possess between 4 and 5 grams would be charged with a class 2 felony, which carries a sentence of $5,000 to $1,000,000 in fines and/or a prison sentence of eight to 24 years.

The draft bill also classifies fentanyl traffickers as “special offenders,” and that also carries a level 1 felony charge.

And those who possess the equipment to make fentanyl, such as a pill press, also face felony charges.

El Paso County District Attorney Michael Allen, however, believes the bill gives a dealer a walk on any charges.

Allen told Colorado Politics distribution resulting in death should not be based on distributed weight, arguing that devalues victims. A high volume is a drug felony one charge with mandatory 12 to 32 years in prison, but, he said, if it’s less than 4 grams and someone dies, it’s not a mandatory prison sentence but rather eight to 32 years with parole a possibility under the proposal.

“That makes zero sense to me,” Allen said.

His biggest complaint, however, deals with the bill’s “Good Samaritan” provision.

Under that provision, if a drug dealer distributes fentanyl and someone overdoses, so long as the dealer calls 911 and cooperates, he or she wouldn’t be charged at all, Allen said. He noted that CRS 18-1-111 says people who use or possess drugs and overdose can’t be prosecuted for seeking help as long as they call it in and cooperate. The bill modifies that section to introduce distribution, making them immune from prosecution as long as they cooperate, according to Allen.

In the Commerce City case last month, in which five people died allegedly from fentanyl overdoses, Allen said if the dealer had stayed there and called for help, that person would have been immune from prosecution.

The proponents and backers, as well as the governor, dispute that interpretation.

Meanwhile, support for the legislation has begun to line up.

In a statement, Attorney General Phil Weiser said he is grateful to the bill’s sponsors for their work and called the proposal “a much-needed stride forward to remove this deadly poison from our streets.” Weiser previously came out in support of strengthening criminal penalties for possessing fentanyl and rolling back that part of the 2019 legislative change.

“By strengthening penalties for those who knowingly or intentionally deal fentanyl and fentanyl-laced substances that kill people, and offering needed funds for addiction treatment and appropriate harm reduction, this bill gives law enforcement valuable tools it needs to remove dangerous fentanyl and high-level drug dealers from our communities,” he wrote. “And rather than criminalizing those struggling with addiction, it provides support and resources for those who need help.”

The proposal includes an expansion of harm reduction strategies in Colorado, broadening who can receive Narcan and naloxone while setting aside millions to pay for more this year, and changing the correctional system’s approach to treating inmates.

It would also create a new fund to pay for strips that can be used to test substances for the presence of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, and it would give school districts and charter schools the ability to supply test strips if their leaders chose to.

As written, the bill allocates $20 million to pay for more opioid overdose antidotes, such as Naloxone, $6 million to expand the state’s harm-reduction grant program this year, and $3 million to help jails develop new withdrawal treatment protocols. The bill does not describe how much money could be set aside for the new test strip fund.

Correctional facilities are acute targets in the bill. Advocates have long said prisons and jails are on the front-line of the crisis, in part because of the intersection of crime and substance use. But overdose rates for people released from a correctional facility are also far higher than the general population. Advocates note that, while incarcerated, users will lose their tolerance for opioids, and when when they’re released and use an opioid at levels they were before their arrest, they’re more likely to overdose and die.

Under the bill draft, correctional facilities would be required to offer opioid agonists and antagonists to inmates with opioid-use disorders. Agonists include methadone and buprenorphine, both of which are used to treat opioid-use disorder. Antagonists include Naloxone and Naltrexone, a medication used to reduce cravings and prevent relapse.

If medically necessary, the bill says, treatment for that inmate will continue throughout their incarceration.

If a person is treated for an opioid-use disorder, has a history of use or requests assistance, the correctional facility, including jails, will give that person at least three dose of an antagonist, such as Naloxone, when they’re released, along with education on how to use it. The facility’s doctor would also be required to prescribe that person medication for treatment, plus a referral to a medication-assisted treatment provider in the area.

Medication-assisted treatment is the use of therapy alongside medications like Suboxone, buprenorphine or methadone to treat opioid addiction. It’s considered by many advocates and public health officials to be one of the best ways to treat someone struggling with opioid use.

Jails who receive state behavioral services program funding would be required to develop medication-assisted treatment or other withdrawal treatment protocols for inmates with opioid-use disorders. The draft bill allocates $3 million to support that effort.

The draft legislation would also require the state Department of Public Health and Environment to “develop, implement and maintain” a fentanyl education and prevention campaign, which would use media advertising, regional training and a website, among other options.

Finally, it would allocate $6 million to expand the state’s harm-reduction grant program, broadening what organizations could receive that money and how they can spend it.

*Editor’s note: This section about bill sponsors has been updated.

Panelists offer diagnoses and potential solutions to the soaring crime rate in Colorado, including rise in fentanyl deaths, in a March 1 forum organized by Colorado Politics and the Denver Gazette.