Marshall Fire weighs on justices as high court considers arson laws

A Jefferson County jury convicted Christopher Magana of arson years before the recent Marshall Fire became the most destructive in the state’s history, but the members of the Colorado Supreme Court wondered openly what the prosecution’s charging decisions in Magana’s case would mean if applied to a much more catastrophic blaze.

The justices heard oral arguments on Tuesday about whether the law authorized prosecutors to charge and a jury to convict Magana for each building he damaged, each piece of personal property he harmed and each person he endangered with the fire he set to his ex-girlfriend’s car. In one exchange, Justice Monica M. Márquez elicited statements from the Colorado Attorney General’s Office endorsing that same approach for the 1,000 buildings destroyed in December’s Marshall Fire.

“Is it your view that there would be 1,000 counts of first-degree arson? And, if we had three people per home, 3,000 counts of fourth-degree arson because of the number of people endangered?” Márquez asked. “Why is that not absurd?”

Senior Assistant Attorney General Carmen Moraleda responded that if a jury found someone had knowingly set the fire, in her view the legislature had authorized a separate conviction in every instance.

“Would it not be absurd for someone who, like the Marshall Fire, gets only one first-degree arson conviction? I think that would be absurd,” she told the court. “Yes, that person would be guilty of as many counts as people endangered.”

Investigators have not yet announced the cause of that fire.

Magana’s case involved a far less destructive blaze that nonetheless resulted in 18 arson convictions. In total, he endangered 14 people, burned two cars and damaged two homes in a duplex after he set his ex-girlfriend’s car afire in Lakewood and it spread to the nearby structure.

“This is too many convictions,” Deputy State Public Defender Rachel K. Mercer wrote to the Supreme Court in her client’s appeal. “Because Magana is only accused of starting one fire, he should only have one conviction for each offense.”

The central question for the court was the intended “unit of prosecution” for arson crimes. Four separate laws govern arson, ranging from first-degree to fourth-degree offenses. First-degree arson, for example, occurs when a person knowingly burns “any building or occupied structure of another.” The other laws similarly criminalize the burning of “any property” and using fire to put “another” person in danger.

As written, the laws gave rise to competing interpretations, with Magana asserting that he deserved one conviction for damaging the buildings, one conviction for destroying property and a third conviction for putting other people in danger. The government, however, maintained that the unit of prosecution is every building, item and person affected, meaning the 18 convictions were in line with what the legislature intended when it enacted the arson laws.

Each side argued that the other party’s interpretation would lead to unjust results. Under the government’s logic, Mercer told the court, a person who sets three separate building fires would have the same consequence as someone who sets one fire that spreads out of control to two other buildings. Prosecutors could also hypothetically pursue separate charges for each item of property – clothing, personal effects – damaged in a fire.

Moraleda responded that lawmakers could not have intended for a person who set one fire to be charged with a single crime if that fire consumed multiple buildings – especially if another arsonist who endangered one person, burned one building and destroyed one piece of property would be subject to three offenses.

Again referencing the Marshall Fire that destroyed 1,084 homes and damaged 149 others in Boulder County, Justice Richard L. Gabriel indicated his unease with adopting the prosecution’s view that “any property” could be used to infinitely stack criminal charges.

“If ‘any’ is what you say it is,” he told Moraleda, “then if you look at the Boulder fires recently, you can probably have 100,000 counts against someone. Every sock, every paperclip – that’s a problem.”

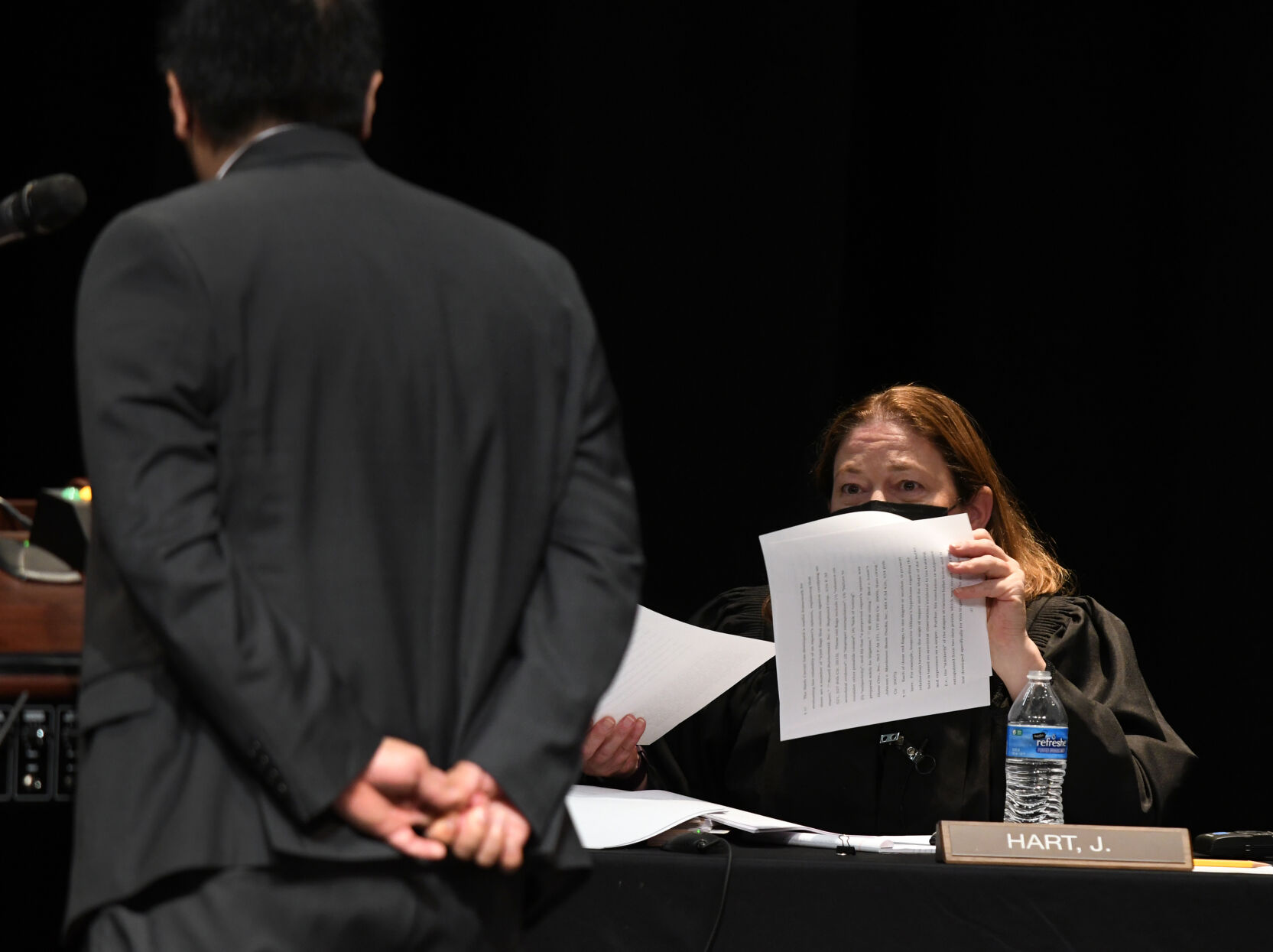

Justice Melissa Hart, raising an issue that neither party referenced, observed that the arson laws require that someone knowingly set fire to property or endanger another. If an arsonist instigated the Marshall Fire by setting ablaze one item or one building, she wondered, “I don’t think you can say he knowingly set fire to a thousand houses.”

Mercer agreed with that point, and reiterated that it was unclear whether the General Assembly provided “clear authorization to impose that many offenses on somebody.”

The justices also weighed a second issue on appeal: whether Magana’s first-degree arson convictions for burning the duplex were violent crimes requiring an extended sentence. The determination hinged on whether fire counts as a “deadly weapon” under the law.

During Magana’s 2017 trial, the jury asked the judge if “fire itself” counted as a deadly weapon. The judge responded that it could be, and the jury accordingly decided Magana’s arson qualified as a crime of violence eligible for enhanced sentencing. The judge declined to impose the sentence, reasoning that because fire was an essential element of arson, every arson would also be a violent crime if fire were a deadly weapon.

The Court of Appeals reversed that decision, finding no evidence that lawmakers intended to exclude fire as a deadly weapon.

The Attorney General’s Office argued that some fires are “ineffective” or do not fully ignite, meaning they would not be charged as violent crimes. Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter seconded the notion that the danger from fires can be situational.

“You also have things like if I’m pissed off at my rancher neighbor and I go set fire to his or her goat shed in the middle of a blizzard. That’s a different circumstance,” she said.

Gabriel was skeptical that a building fire could be legally broken down by degrees of seriousness.

“I‘m having trouble buying an argument saying, ‘It was just a wee bit fire’ or ‘it was an unoccupied structure’,” he said. “How is it, in the context of first-degree arson, not always a deadly weapon?”

Mercer believed that, in the absence of an answer, prosecutors could treat two arsonists differently, charging one with a violent crime and declining to pursue an extended sentence for another. It could violate constitutional protections, she warned, to subject them to different penalties for the same conduct.

The case is Magana v. People.