State plans to rely on federal one-time money as youth mental health advocates call for funding

A coalition of families and youth mental health experts this week called on government policymakers to invest in services to address the state’s youth mental health crisis. But will their request – a $150 million investment in one-time only federal funds – cover children whose mental health needs can go on for years?

Children’s Hospital declared a youth mental health state of emergency back in May, pointing to escalating rates of suicide attempts between youth ages 10 to 24 years old.

On Tuesday, the hospital said in a news release that federal and local government officials have a responsibility to prioritize mental health policies and funding to support children, youth and families.

Jake Williams of Healthier Colorado specifically called on Gov. Jared Polis and the Colorado General Assembly to invest $150 million from the state’s share of federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) money for youth mental health prevention, treatment and recovery. That represents one-third of available ARPA money, and advocates identified it as a funding source because children make up a third of the state population, Williams said. But those dollars have a limit: they must be spent by Dec. 31, 2024, according to US Treasury guidelines.

The coalition suggested three areas where that money should go:

- Strengthen workforce and caregiver supports so the supply of providers meets the needs of children and reflects the populations they serve

- Expand the care continuum so that children have culturally competent settings in which to receive care tailored to their acuity, geography, and other factors

- Build a cohesive system that unifies programs to function as a whole so that families served by multiple programs can experience seamless coordination

Children’s Dr. David Brumbaugh said in May that “there have been many weeks in 2021 that the number one reason for presenting to our emergency department is a suicide attempt. Our kids have run out of resilience – their tanks are empty.”

Not much changed six months later, according to Brumbaugh.

“Unfortunately, we are still in a state of emergency,” he said.

On any given day, 40-50 children come to emergency rooms in the Children’s Hospital network in acute mental health crises, he added.

Brumbaugh is among the experts who participated in a media roundtable to discuss the The Children and Youth Mental Health Playbook, developed by Children’s Hospital, Healthier Colorado, the Colorado Education Association, the Colorado Association for School-Based Health Care, and the the Colorado Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The playbook doesn’t rely only on ARPA money. It also calls for local governments to fund local efforts to bolster programs for respite care for families with complicated mental health needs, pay for local services for in-home crisis response, establish prevention programs tied to “voluntary lock boxes to secure items away from children and youth” and drop-off sites for prescription drugs, and establish mental health crisis intervention teams that would work with local emergency medical services providers.

One father talked of the anguish he and his family faced when one of their children needed mental health care but couldn’t find what they needed in Colorado.

Jim Wiegand said his family struggled when trying to find help for a daughter. Adopted at 4 years old, she came with a lot of trauma, he said. Medical professionals initially tried to convince the Wiegands to have her institutionalized, but he said he and his wife wanted to try and work with her. When she was younger, they were able to find therapy for her, but as she got older, and into middle school and puberty, “the trauma dam burst.”

That’s when they tried to get her services through Medicaid or through residential treatment. They eventually had to go to the county to have them take partial custody, and she then went through multiple residential treatment programs for the next two years. Administrators of the last program, in Colorado, told the Wiegands they couldn’t help her, and there was no place else within the state for her. She wound up in a facility in Georgia.

“It was the best treatment facility we could ask for her to be in, aside from the fact that it was 1,500 miles away,” he said. However, the distance limited visitation, particularly during the pandemic.

She’s been home now for two months, and the treatment she received is evident, he said. She’s thriving in a day treatment school and doing well. She wants to be a mentor and help others, and it’s evident that she’s gained clear perspective on the need for mental health services, he said.

Wiegand said the problem was having to go out of state to get the help she needed.

“We were lucky that we had the means and ability to engage with our child and really advocate for her,” he said.

Weigan has also met others who face the same struggles and are “silenced by the frustration they have with the current system.” Some children wind up in the hospital for six months because there’s nowhere else for them to go, he said.

Wiegand described the current mental health system as a black hole, one that he said fails children and doesn’t allow parents to navigate.

The Wiegand’s situation point to the years, rather than months, that it takes some families to find the help they need, especially for teens, according to advocates.

Until recently, Colorado was more reliant on state funds to cover the costs of mental health services for kids rather than federal resources. A 2018 analysis of early childhood mental health services by the Colorado Health Institute showed that the state invested $42 million, or about 68% of the total spent, compared to $13 million (20%) from the federal government, to serve children 0 to 8 years old during the 2017-18 fiscal year. But the analysis also showed that “statewide, the 12 programs analyzed are serving less than 10 percent of children aged zero to eight. Even in the best of cases, no county is providing services to more than a third of children. The funding supporting those programs, philanthropic investment and governmental funding combined, represent about $102 investment per child aged zero to eight.”

The analysis called the level of spending inadequate.

More recently, the state turned to to the federal government (and federal dollars) to bolster those efforts. In the current year budget, for example, mental health services paid for by the Office of Early Childhood saw more money budgeted from federal funds ($39 million) than from the state ($31 million).

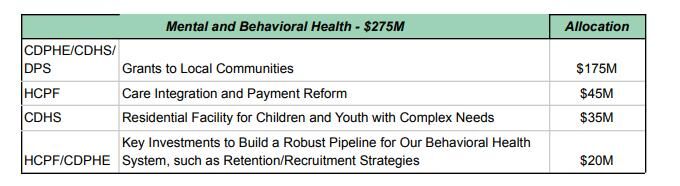

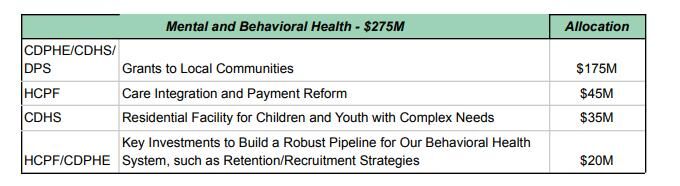

In his 2022-23 budget request, Polis pointed out that he directed $32.2 million in discretionary federal funds, including $11.9 million in emergency funding, to expand residential options that can serve youth with acute behavioral health needs.

“The current lack of coordinated, integrated services and appropriate care settings often results in limited access to care. Further, COVID-19 has resulted in significant hardship on our state’s public and private behavioral health providers,” Polis said in the budget submission.

During the 2021 session, the General Assembly set up a behavioral and mental health cash fund with $550 million in one-time ARPA dollars. Of that, $100 million was spent during the current fiscal year, mostly on opioid treatment, workforce development and housing assistance. About $10.5 million went for mental or behavioral health services for youth, including a $5 million residential treatment pilot program and $500,000 for an Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation Program.

Brumbaugh said Tuesday that SB 137, which created the cash fund, was a good start, but more is definitely needed.

The recommendations from the task force on how the rest of the $450 million is to be spent has not yet been submitted to the governor or General Assembly.

Polis outlined his top priorities for how to spend that one-time money in his budget request.

But what happens when those dollars run out at the end of 2024?

State Rep. Dafna Michaelson Jenet, D-Aurora, pointed out that Polis may have submitted his own ideas for that money, but it’s the General Assembly (and its Joint Budget Committee) that will make the final call. Michaelson Jenet is a member of the interim Behavioral Health Transformation Task Force that is crafting recommendations on how to spend that money.

She said despite the reliance on one-time federal dollars, those funds will temporarily help the state stretch its existing resources.

Michaelson Jenet said policymakers are looking for ways to leverage community dollars, which are also referenced in the governor’s budget request.

“That may be part of the answer for ongoing funding,” she said.

She also pointed out that about 60 to 70 young people every year get sent to behavioral or mental health facilities out of state.

“That’s very expensive,” she said. “By building the facilities and training the workforce instate, we will be able to utilize an ongoing budget line to create better opportunities for our kids at home. That’s transformational.”