Emergency responders address mental health crises in Colorado Springs community

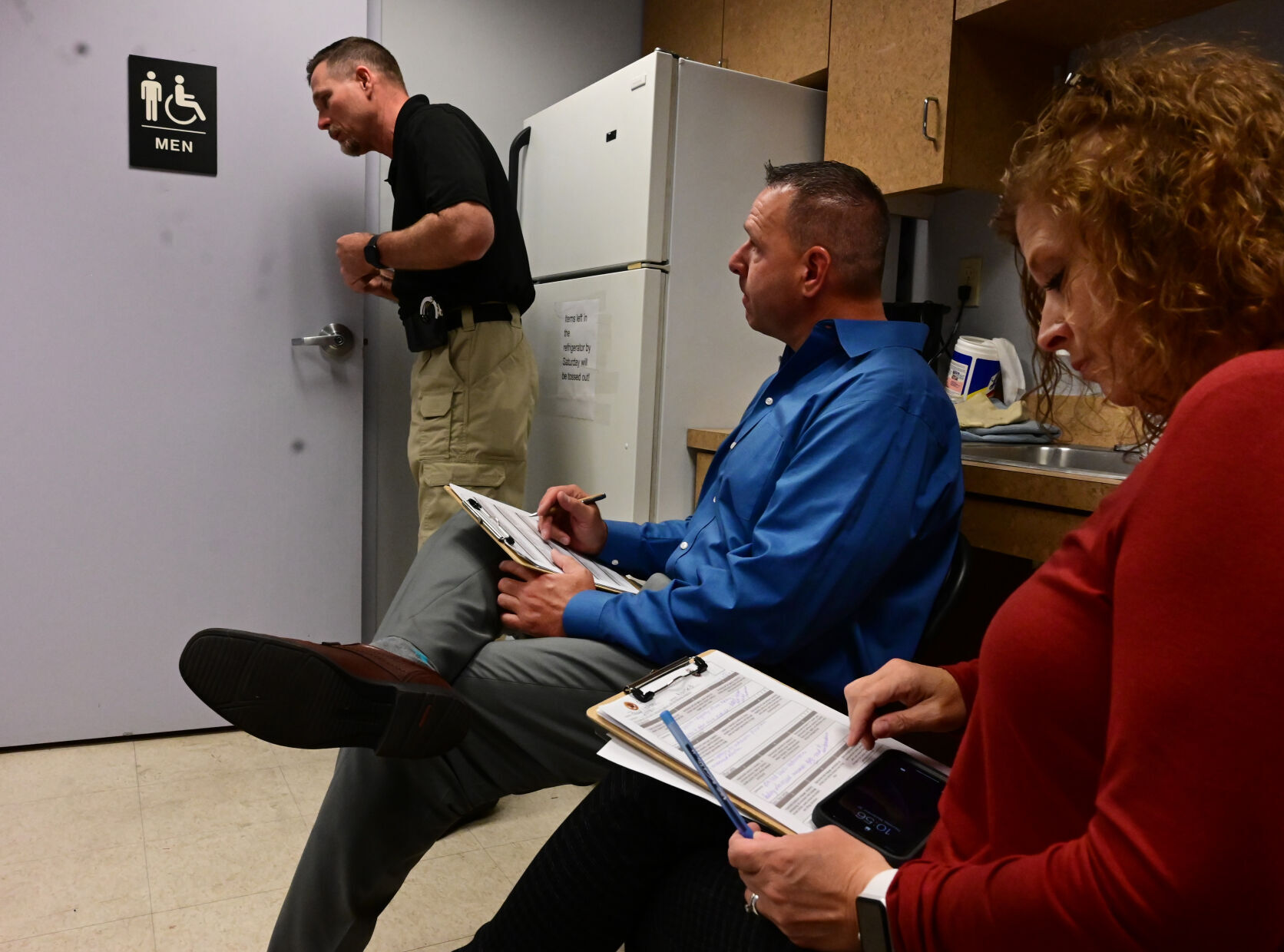

Paul Hollen with the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office talks to a female actor who’s being paid to pretend to be having mental issues in the men’s restroom on Thursday, Sept. 30, 202. Hollen and other law enforcement were doing the training to get their crisis intervention certification. The training will help them to handle mental health crisis situations. Unoccupied spaces at Chapel Hills Mall are serving as a training facility for . Training facilitators Nikki Patton and Brad Krause, with the CSPD, monitor Krause and work with him on the best ways to handle the situation. (Photo by Jerilee Bennett, The Gazette)

Jerilee Bennett

As downtown commuters jostled for parking spaces on the morning of Aug. 18, a lone man edged out on a ledge atop a garage off Kiowa Street.

Naked and depressed, the man didn’t budge as the first officers officers tried to coax him back from the edge. Swarms of officers came to assist and an inflatable cushion was placed in an alley to catch the man if he made the suicidal seven-story leap.

After responding to 9-1-1 calls for 4,872 suicidal residents in 2020, police are repeating the frenetic pace in 2021, with officers forced to act as ad-hoc psychologists as people contemplate self-inflicted death.

“Dealing with mental health is very common,” James Coffey a deputy with the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office, said.

In 2020, 178 residents died by suicide, a number that police want to reduce.

Coffey and his fellow deputies joined officers from the Colorado Springs Police Department and other emergency response personnel including dispatchers, at a crisis intervention training program this week.

The 40-hour training program educated police and deputies on mental illnesses as trainers moderated scenarios law enforcement might encounter, including how to talk residents out of suicide.

Sgt. Eric Frederic, the coordinator for the crisis intervention training, said it is stressful for students.

“But at the end of the class, all the students say this is the best training we’ve ever had because it’s so specific,” he said.

The first 20 hours of the course includes classroom training with mental health professionals followed by 20 hours of scenario-based training.

Professional actors simulated residents facing problems from manic behavior to alcohol-fueled binges.

The actors are given a set of parameters for the scene but beyond that — it’s all improvised.

“We’re helping the cops to avoid going hands-on,” explained Joe Wilson, the owner of acting group, Twopenny Productions LLC. “We’re trying to give them the tools to communicate with the mentally challenged population in ways that don’t involve drawing a weapon or pulling a taser.”

In one scenario, Deputy Coffey faced a man with a scraggly gray beard sipping from a vodka bottle, groping for pills strewn across the ground. The bearded actor had a toy pistol within reach.

“We’re very blessed to be able to have this training,” Deputy James Coffey said. “… I feel it’s important for all law enforcement to be able to have a better understanding with how to communicate with the community.”

Coffey got down on the man’s level and tried to engage him, asking him questions and encouraging him to come to the hospital.

“I felt like we were connecting,” Coffey said after his scenario ended successfully.

While police are often the first line of defense when it comes to responding to people in crisis, the city also created a more targeted approach for those with mental health issues known as the Community Response Team.

The Community Response Team — a specially trained group consisting of a police officer, firefighter paramedic and a mental health clinician — responds to behavioral health calls and provides patients with immediate support and long-term resources tailored to the patient.

The program is designed to respond to behavioral health crises from the 9-1-1- system and the state crisis line to help address emergency calls more effectively and offer more targeted care.

Of the 4,872 suicide calls police received in 2020, the Community Response Team responded to between 23-25% of them, plus a host of other behavioral health calls.

The team strives to pair people who are not in immediate danger with the right resources. Sometimes that means transporting them to a mental health facility or creating a safety plan and scheduling follow-up care.

“It’s very effective,” Lt. Andrew Cooper, supervisor for the Community Response Team, said.

And its effectiveness is sustained by following up with patients, Coopers said.

“We also have a mandate in place to reach back out to them within certain timeframes and really do that follow-up, which is really important,” Cooper said. “So it’s great to have response, but response without follow-up doesn’t result in follow-through.”

As the morning wore on Aug. 18, Colorado Springs police, talking carefully and quietly, got the would-be parking garage jumper wrapped in a blanket.

They talked with him all the way to the ambulance.

“Recognizing the devastation that it (suicide) is to the community and what that does to the families … I’ve always had an interest in how we can better serve,” Cooper said.

Death of Colorado Springs pastor leaves ‘a void’ among community

Several people sent to hospital after suspected DUI crash, police say

Colorado Humane Society, sheriff’s office rescues 2 horses in Fremont County

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: