BARTELS | Where there’s smoke, there’s barbecue — and Adrian Miller

Adrian Miller once dreamed of becoming a U.S. senator and while his career is definitely smoke-filled, it’s not in some back room. Instead, it’s anywhere there’s meat, heat and sauce.

The Colorado native, who bills himself as a recovering lawyer and politico, is now the ultimate foodie, writing award-winning culinary books, penning articles on soul food and judging barbeque competitions across the country.

Miller has a busy schedule for Black History Month. On Feb. 1, he appeared on the “The Drew Barrymore Show” judging ribs. That night he was part of the virtual “Flatirons Food Film Festival: Keepers of Black American Food Culture,” where he interviewed the movie director.

This was not the path Miller planned for himself when he graduated from Smoky Hill High School in Aurora in 1987, Stanford University in 1991 and Georgetown Law School in 1995.

Miller went on to serve as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton, overseeing his initiative for One America, the first free-standing office in the White House to address issues of racial, religious and ethnic reconciliation.

Talk about the perfect credentials for a future U.S. senator from Colorado.

When Clinton left office in early 2001, Miller stayed in D.C., where he looked for a job in a slow economy and watched a lot of bad TV. He finally got off the couch, ventured to a book store and found one that spoke to him: John Egerton’s “Southern Food: At Home, On the Road, In History.”

Egerton believed that the tribute to Black achievement in American cookery had yet to be written, and so Miller emailed him to see whether, 14 years later, the author still held that sentiment. Egerton did.

“And so with no qualifications at all, except for eating a lot of soul food and cooking it some, I set out to write a book,” Miller said.

He returned to Colorado, where he worked the next six years for the Bell Policy Center, an organization with a mission to “ensure economic mobility for every Coloradan.” In other words, the group spends a lot of time explaining why the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights is so bad for the state. All the while, Miller chipped away at his book.

In 2004, about the same time that U.S. Sen. John Kerry won the Democratic nomination for president, Miller read an ad in the Rocky Mountain News about judging a barbecue competition. But first Miller had to take a judging class.

Miller said when he walked into the classroom at the Adams County Fairgrounds, he was the only one of his 70 or so classmates who weighed less than 250 pounds.

“I thought if that’s my future I can deal with it,” Miller recalled with a laugh.

The class was taught by the Kansas City Barbeque Society, and those who signed up were taught how to judge barbecued pork shoulder and ribs, brisket and chicken. The results were graded on a nine-point scale for taste, texture and appearance. They learned what garnishes could be served with the meat and other judging rules.

I met Miller in 2007 when he joined Democratic Gov. Bill Ritter’s administration, first as the deputy legislative director and then as a senior policy analyst.

During this time the Rocky closed, and The Denver Post hired me.The Post’s political editor, Curtis Hubbard, wanted articles about the Ritter administration and I suggested Miller – and not just because I love ribs so much I’ve been known to moan when eating them.

I thought it was a great story and I could just see the headline: “Bureaucrat on weekdays, barbecue judge on weekends.” To my consternation, Hubbard nixed the idea.

Ritter didn’t run for re-election in 2010, and Miller decided to write full time.

“It was the worst move economically, but in terms of my happiness it was the best move ever,” Miller said.

In 2013 he published “Soul Food: The Surprising Story of American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time.”

“In this insightful and eclectic history, Adrian Miller delves into the influences, ingredients and innovations that make up the soul food tradition … and what it means for African American culture and identity.” one review read.

“This refreshing look at one of America’s most celebrated, mythologized, and maligned cuisines is enriched by spirited sidebars, photographs and twenty-two recipes.”

To Miller’s surprise, his book won the James Beard Foundation Award for Scholarship and Reference in 2014. Think about it: James Beard. That’s one heck of an endorsement for a career change.

At word of the honor, I couldn’t resist poking Hubbard on Facebook about rejecting a piece on Miller. Looks like I was the one with news judgment, I said.

“Turns out it was a delicious story, so I can only surmise that pitch from the reporter must’ve been weak sauce – or maybe that hard news was the order of the day,” Hubbard now jokingly says.

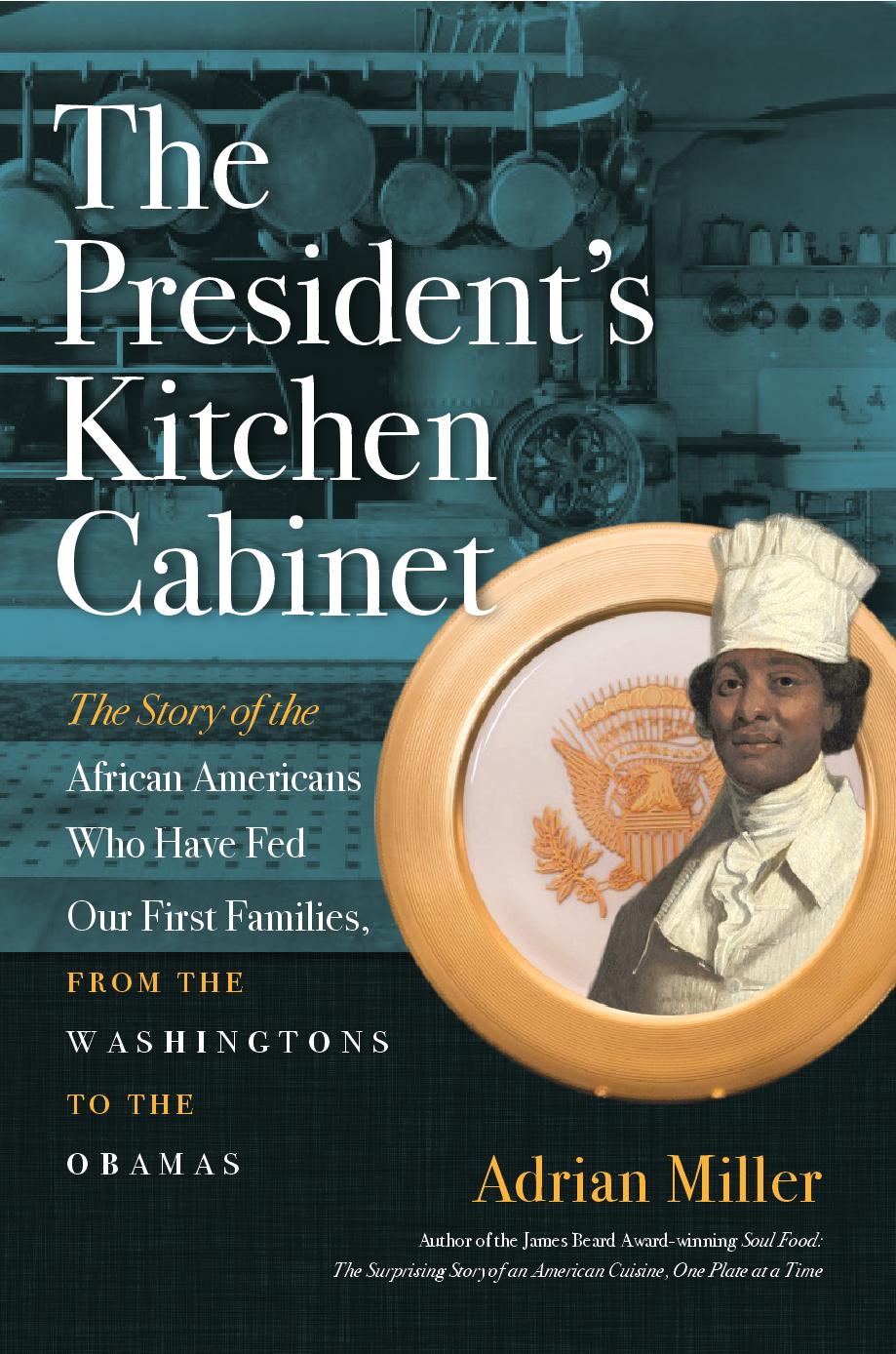

Miller wrote a second book, “The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed our First Family, from the Washingtons to the Obamas.” It was a finalist for a 2018 NAACP Image Award for “Outstanding Literary Work – Non-Fiction.”

In addition to recipes, the book includes some “unforgettable events in the nation’s history,” according to a review from Barnes & Noble.

“Daisy McAfee Bonner, for example, FDR’s cook at his Warm Springs retreat, described the president’s final day on Earth in 1945, when he was struck down just as his lunchtime cheese souffle emerged from the oven. Sorrowfully, but with a cook’s pride, she recalled, ‘He never ate that souffle, but it never fell until the minute he died.’ “

Miller’s third book, “Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbeque,” will be published this spring. He was inspired to write it, he said, because although Blacks have long been identified as the linchpin for soul food and Southern food, they have been mostly ignored when it comes to barbecue.

It is telling, he said, that for a while the Black cook most identified with barbecue was Freddy on the TV show “House of Cards.”

“And he’s a fictional character!” Miller said.

As for consuming barbecue, Miller’s favorite joint in Colorado was the Black-owned Boney’s Smokehouse, which has closed, another victim of the brutal coronavirus pandemic.

But Miller said some other restaurants “are doing really good stuff” when it comes to barbecue. He listed Owlbear on Larimer, Roaming Buffalo on Downing, Hank’s on Colfax, Post Oak on Tennyson and Smok in Rino.

In an interview last year with Channel 7, Miller talked about the history of barbecue in Colorado.

“One thing to understand is after emancipation, all of these African-Americans who had been doing plantation barbecues as enslaved people, basically they become barbecue ambassadors,” he said.

One of those barbecue ambassadors who moved to Colorado was Columbus B. Hill from west Tennessee, who did a barbecue for 25,000 people when the cornerstone for the state Capitol was laid on July 4, 1890.

More than a century later, Miller would work in that building, another ambassador for barbecue.