Rural hospitals face increased risk, exacerbating rural Americans’ health care crisis

A new report from Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, says that rural Americans are in poorer health than their urban counterparts, and that rural hospitals face more challenges in keeping their doors open now more than ever.

“Not a day doesn’t go by that I don’t thank God I’m an academic and not the CEO of a rural hospital,” Dr. George Pink told Stateline. Pink is a health policy professor and deputy director of the rural research program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

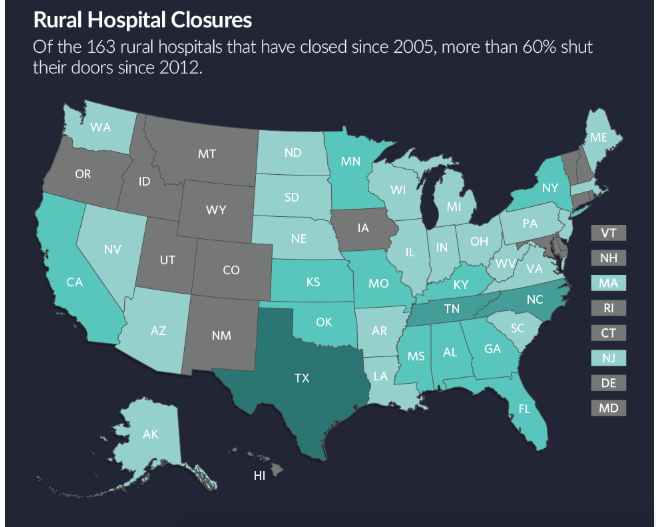

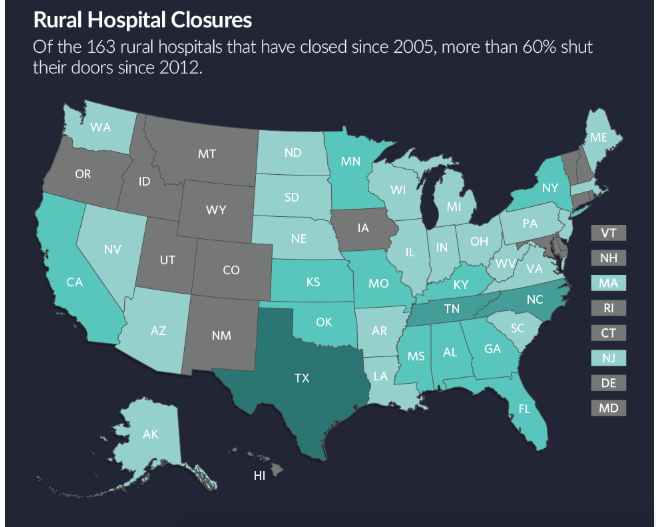

Over the past 15 years, 163 rural hospitals have closed nationwide, according to Stateline.

While Colorado has so far dodged the bullet in terms of closures of rural hospitals, they’re operating on the slimmest of margins, or not at all.

Julie Lonborg of the Colorado Hospital Association told Colorado Politics that Colorado “has been incredibly fortunate and we’ve worked very hard in this state not to have a hospital on that list. That said, we do have vulnerable hospitals,” with Memorial Hospital in Craig one of the most challenged.

Lonborg points to changes in the way hospitals are paid or deal with expenses as one of the most recent challenges. Two bills passed in the 2019 session added to the instability, she explained: HB 1168, the reinsurance bill, and another, HB 1174, on out-of-network charges.

The reinsurance law requires Colorado hospitals to kick in $40 million per year, to be split among the hospitals. Lonborg said that until just two weeks ago, hospitals had no idea what their share of that reinsurance fee would be. “If they’re truly vulnerable and working every day to make ends meet,” knowing that they have an expense on the way but don’t know how much is a concern, she said. And she said the hospitals had been assured that rural hospitals would be “carved out” of the reinsurance fee, but that didn’t happen.

The proposed public option law is another concern for hospitals’ bottom line, she said. “We don’t know yet what that means,” but as proposed, hospitals would be mandated to participate, and that would include state-designed caps on hospital costs of care. The hospital association also had been assured that rural hospitals would be spared, but are skeptical, based on the promises not kept with reinsurance.

Lonborg said 36 hospitals in Colorado, not all of them rural, operated in the red in 2018, based on cost reports. Another 46 are operating below the nationally-agreed upon threshold for sustainability, which is 4%. Lonborg explained that if a hospital isn’t making at least 4%, they don’t generate enough cash flow to keep up with new technology, or replacing equipment or infrastructure, including those mandated by the federal government.

The hospital association would prefer to see carve-outs within the public option proposal based on those kinds of factors, not just where a hospital is located.

“If you were hearing that your pay might be cut in half, what would you do personally? You’d be conservative and pare back expenses,” she said. Hospitals do the same, and that’s what’s driven improvements in profitability, as was cited by the Polis administration last week. Lonborg said those profits ward off changes in the bottom line driven from “threats at both the state and federal level.”

A report released Jan. 7 by FTI Consulting Inc. and Colorado’s Health Care Future (which is funding a six-figure ad campaign against the public option) said 23 rural hospitals would be at greater risk if the public option proposal, as it was announced by the Polis administration late last year, became law.

“Hospitals in areas like Alamosa County, where fewer than 20% of patients are covered by commercial insurance, would be left with few options and could be forced to eliminate services, close facilities or lay off workers,” the report said.

“Such measures have direct implications for access to care in underserved areas.”