Denver’s Stapleton neighborhood grapples with namesake’s KKK past

Colorful and inviting banners flutter in the wind above a popular shopping and dining area in Denver’s Stapleton neighborhood where an airport once stood.

“We are One Community,” reads a banner with a kite next to it. It is followed by a set of banners that read:

“We Care”

“We Respect”

“We Welcome”

And on the lamp posts are a set of smaller banners that declare “Respect your neighbor…”

“…who doesn’t think like you.”

“…who doesn’t look like you.”

“…who doesn’t love like you.”

Gone, however, is one last banner that read “We are Stapleton.”

That one irked a group of residents who are trying to convince their neighbors that the time has come to shed the name “Stapleton” and cut ties with Benjamin F. Stapleton, a Denver mayor nearly a century ago who was once a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

They also objected to the sign’s appearance at a time when an election is underway among the community’s 12,000 property owners to decide whether to change the legal name of the development to something other than Stapleton.

Ballots were mailed out in mid-June; voting ends Wednesday.

Keven Burnett, the executive director of the Stapleton Master Community Association, said the idea for the banners came from another town that ran a similar campaign.

“We thought, yeah, that is this community. It’s a very welcoming, diverse, open and welcoming community,” Burnett said recently.

But soon after the banners went up, Burnett said officials decided to remove the “We are Stapleton” banner.

“We’re going through this vote right now,” he said. “It’s probably most appropriate that we leave that off and just come back to one community.”

The banner incident goes to the heart of why organizers of the campaign are seeking to rename their community, which spans some 4,500 acres where Stapleton International Airport was once located.

“As a resident here, I see it as my responsibility to use what power I have and what voice I have to kind of bring attention back to that issue and to kind of correct course,” said Liz Stalnaker, chairwoman of a citizen group called “Rename St*pleton for All” that is pushing for the name change.

Stalnacker said Benjamin Stapleton’s history of involvement with the KKK when he first served as mayor in the 1920s seems incongruent with a community that prides itself on an urbanist vision of a diverse and welcoming place.

“… There’s a name of a Klansman on this [neighborhood] that seems to be at odds with these values we’re espousing,” she said.

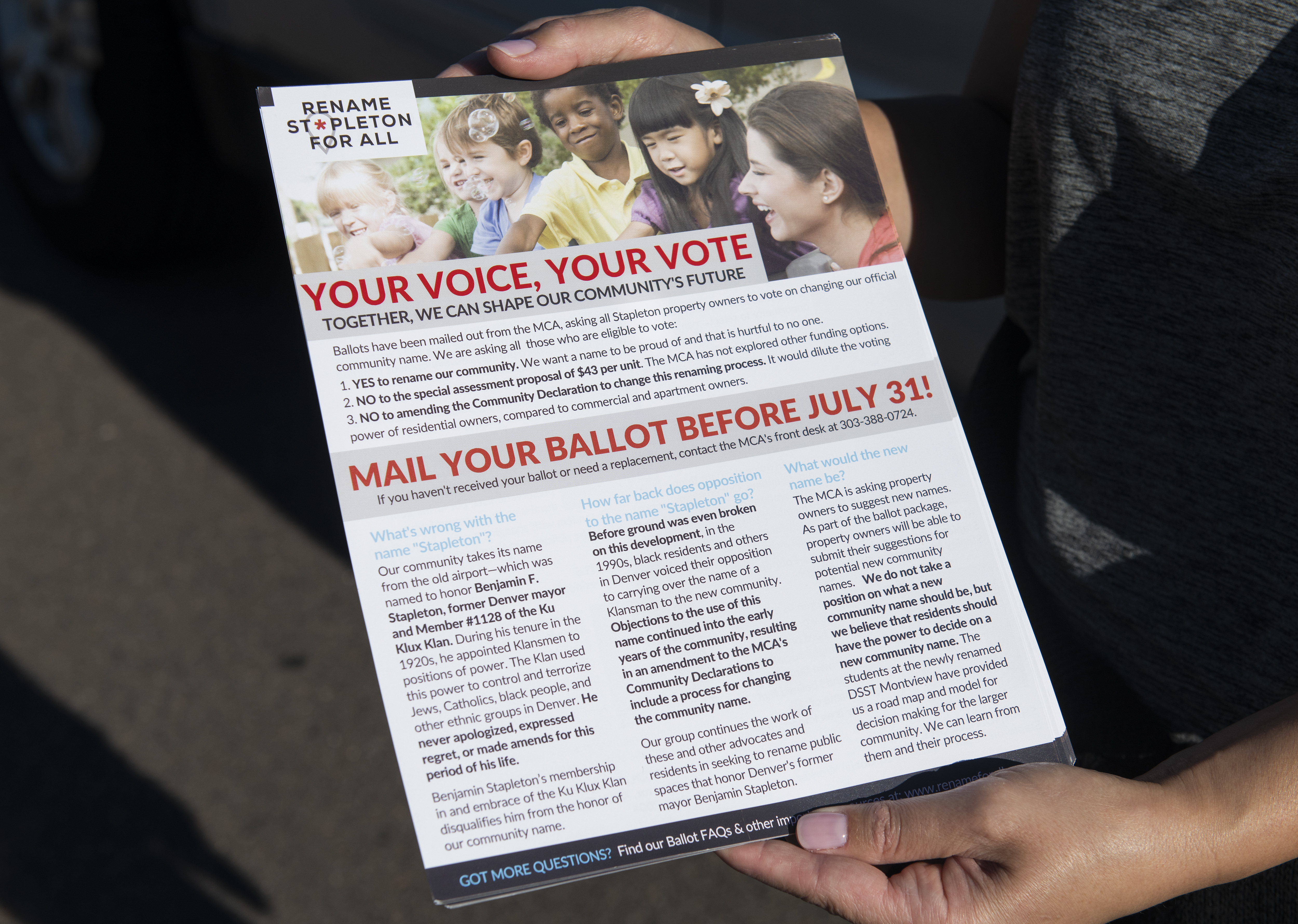

Rename St*apleton advocates have taken their campaign door to door with volunteers canvasing and handing flyers out to residents.

They also hosted a number of “community conversations” at various locations within the neighborhood.

The flyers contain comments from several people, including one from Vince Collins, a resident since 2006.

“The community has a unique opportunity to select a name that aligns more closely with our values. Symbols matter, particularly in these politically fraught times,” Collins said.

No organized opposition has emerged to the name change, but there’s been plenty of debate on social media platforms and in the community newspaper.

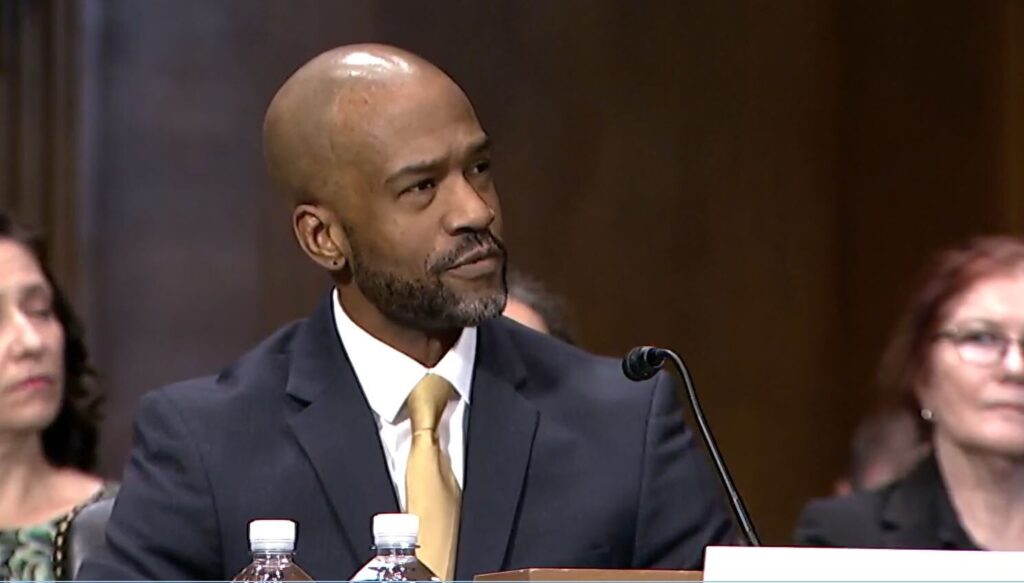

Denver City Councilman Chris Herndon, whose district includes Stapleton, said he does not believe a name change is needed.

“In my opinion, I think the name Stapleton is a positive, not a negative,” Herndon told Colorado Politics.

“I think about a community that says no matter where you are in economic status, no matter who you are as an individual, there’s a place for you,” he said, citing recent efforts to build affordable housing in the community.

Herndon said that as an African-American, he has felt very accepted in Stapleton over the last decade.

He said he is also proud of the way the community responded to an incident when someone spray-painted racist graffiti on a school.

“What I was really proud of was the community’s response, how we came together and said this is not who we are and even held an event to demonstrate that as well,” Herndon said.

“When people who have hate in their heart try to come in and do something negative, we respond with positivity,” he added.

Opposition to the use of the Stapleton name goes almost as far back as the early day of developing the former airport property. Several black activists from the neighborhoods near the airport made their objections known to executives with the developer, Forest City.

The name endured. But in 2003 Forest City amended its Community Declaration to include a process by which the name could be changed.

Meanwhile, the Stapleton neighborhood continued to grow. Then on Aug. 8, 2015, a group of Black Lives Matter 5280 activists distributed flyers to the community. The flyer cited Ben Stapleton’s history with the Klan and urged that the name be changed.

Since that action, several other organizations that used the word Stapleton have re-examined their use of the name.

The Stapleton Foundation, a nonprofit that was created in 1990 to draft a plan for the former airport, changed its name in 2018 to The Foundation for Sustainable Urban Communities.

Foundation CEO Landri Taylor said he and others had been thinking of the name change even before the protests happened.

Taylor said the “footprint” of the foundation’s mission of providing wellness and education and other programs had expanded over its 20-year history to communities well beyond Stapleton.

He said the foundation has done work all over Colorado and in cities in Texas and Florida.

So, when the name change came up at a board meeting in December 2017, Taylor said it took only a few minutes before the board settled on the new name.

Around that same time, students at the Denver School of Science and Technology had been researching the history of the Klan in Denver when they decided to advocate to drop Stapleton from their school’s name.

As a result, the school’s name changed in May to DSST: Montview, taking its new name from the boulevard that runs through northeast Denver.

Members of the Stapleton United Neighbors voted on May 15 to change their organization’s name.

While the members voted 261 to 189 for the name change, they did not have the required 66% of the ballots cast for the change to take effect, said Amanda Allshouse, president of the group.

Asked if it is awkward for the name to remain when a majority of members voted against it, Allshouse said, “I would love for the community to feel united around all aspects of our culture. It’s currently not the case on that issue.”

When the issue of the name at Stapleton first came up in the 1990s there were only two equal stakeholders, the city of Denver and Forest City, and Burnett, the Master Community Association’s executive director.

Now there are 12,000 stakeholders, each of whom will have a say through the mail ballot election.

The state laws that govern special districts like Stapleton require that ballots go one to each property owner, he said. That includes homeowners and businesses, but not rental tenants.

Burnett said the association functions mostly like a large parks and recreation district, overseeing about 50 parks, seven large outdoor pools and activities like outdoor movies, farmers markets and other programs.

While the Master Community Association holds elections for delegates to its governing board, the name change vote presents a special challenge, he said.

“We do not run an elections commission. This is a little bit outside our wheelhouse,” he said.

The ballot will ask voters three questions:

? Should Stapleton be dropped from the legal documents that apply to the community?

? Should there be a one-time $43 assessment for each property owner to fund a search for a new name if the first question passes?

? Should the election process be changed if there are any future elections?

Burnett said the assessment would amount to $300,000 to hire a consultant to oversee the search for a new name.

“There is not another name that can be switched out without significant community input,” he said. “You can’t leave that space blank.”

Rename St*pleton for All is opposed to the assessment fee question, arguing that the work of finding a new name can be done for less.

Burnett said if the first questions passes and the assessment fee question fails, the association will have to look within its existing budget to make up the difference.

The association will continue to collect ballots up until 7 p.m. on Wednesday.

–

–

–