Colorado subject of ‘BlacKkKlansman’ thrilled by Oscar nominations

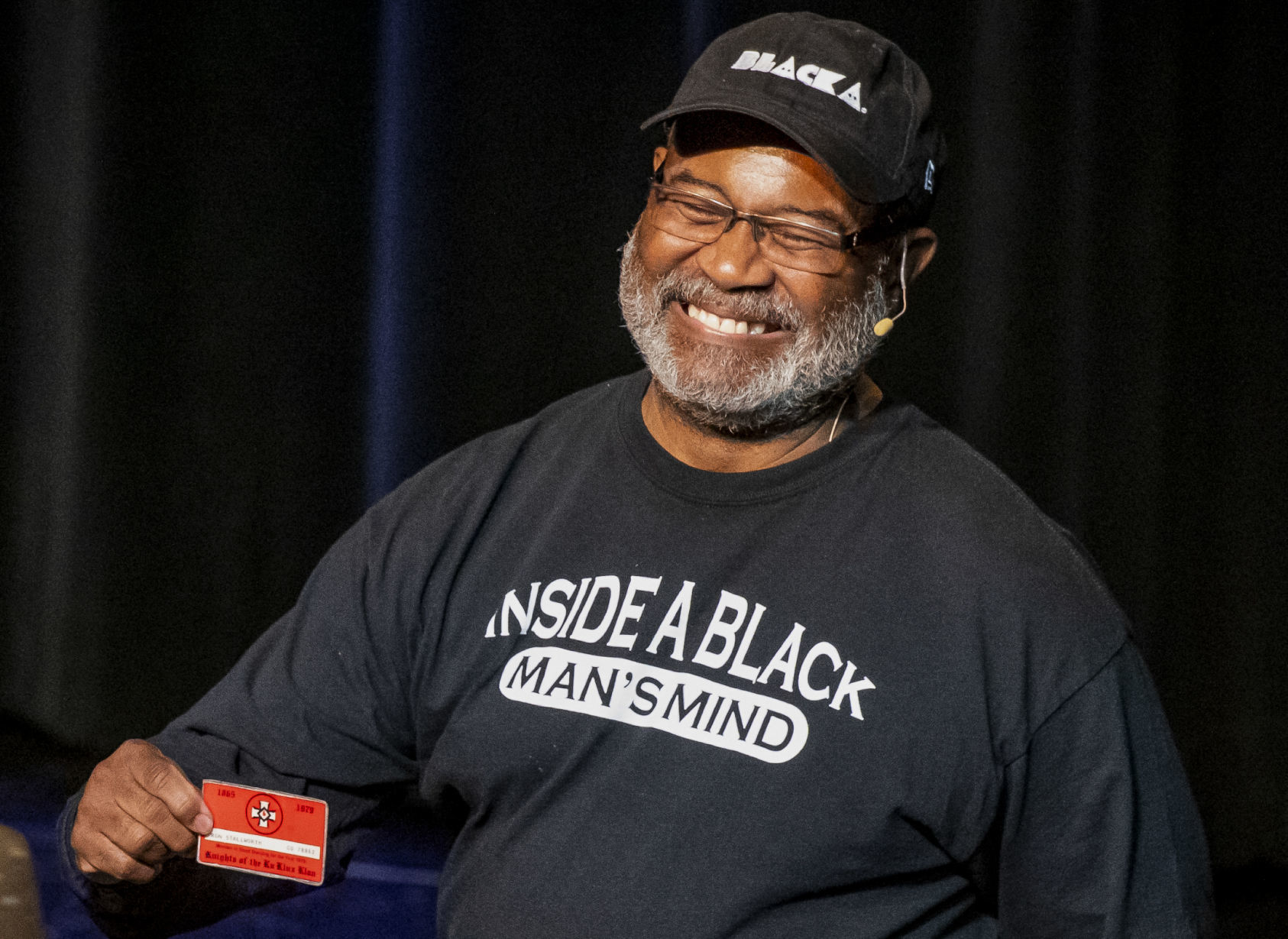

In continuing his promotional tour around the country, Ron Stallworth on Tuesday landed in Iowa, where the snow and gray skies could do nothing to dampen his mood.

“If you saw the smile on my face, it would blind you,” he said.

Stallworth, Colorado Springs’ first black police detective, is the real-life subject of “BlacKkKlansman,” which on Tuesday nabbed six Academy Award nominations, including one for best picture.

> RELATED: Dick Cheney: Give that man an Oscar …

Spike Lee is up for best director, and the movie also earned a nod for best adapted screenplay, based on Stallworth’s 2014 memoir, “Black Klansman: Race, Hate, and the Undercover Investigation of a Lifetime.”

Now living in his native El Paso, Texas, Stallworth is planning to be in Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre for the 91st Oscars on Feb. 24.

> RELATED: ‘Black Klansman’ author Stallworth speaks to capacity crowd in Springs

“Mainly, it’s a validation of my story,” he said. “An acknowledgement that what I experienced was a valuable moment in time that hopefully people are benefiting from.”

John David Washington plays Stallworth, who in 1978 went undercover to infiltrate the local Ku Klux Klan. The mission was alongside a white partner, played by Adam Driver, whose performance netted him a best supporting actor nomination. (Stallworth refers to his former partner as Chuck in the book; in the movie he’s called Flip Zimmerman.)

> RELATED: New Spike Lee movie ‘BlacKkKlansman’ is based on Colorado case

Stallworth communicated with the Klan over the phone, while Chuck represented him in face-to-face meetings.

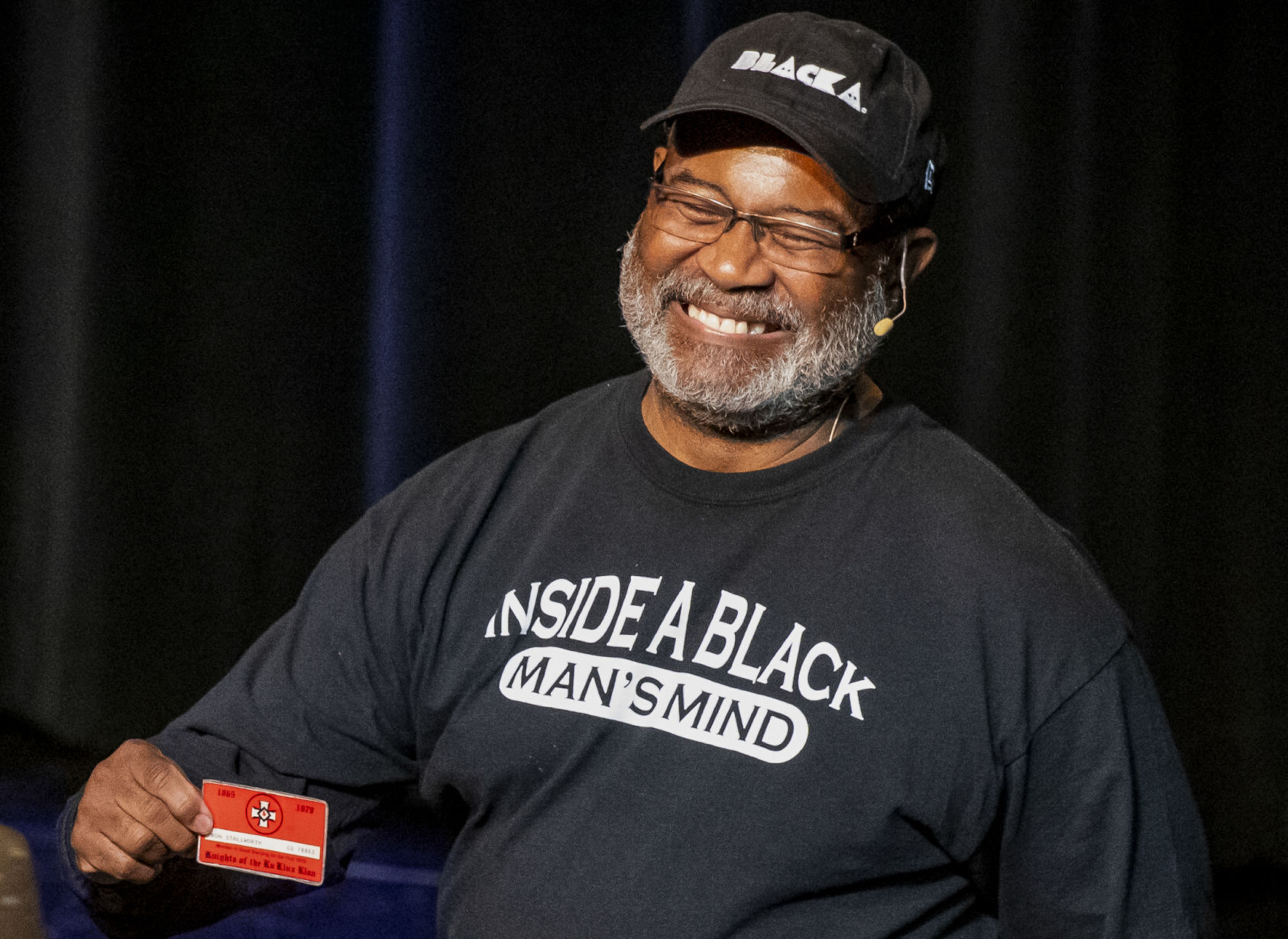

Stallworth’s bold investigation included calls with Klan leader David Duke, who signed the certificate of KKK membership that Stallworth keeps today. He also still carries the red ID card marking him “in Good Standing for the Year 1979.”

The humor of those conversations with Duke – the “Grand Wizard” compliments Stallworth for his “Aryan” voice – was not lost on Lee, whose depictions of lower-ranked knights also garner uncomfortable laughs.

But “BlacKkKlansman” has a serious purpose. It’s loud and clear at the end with stark reminders of Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally, which happened a year prior to the date the movie opened in theaters.

“[H]atred has never gone away,” Stallworth writes in the latest edition of his book, “but has been reinvigorated in the dark corners of the internet, Twitter trolls, alt-right publications, and a nativist president in Trump.”

He has spread that message while touring the country the past year.

“You have to stand up to racism and to hatred and to people like the KKK and others in white supremacy,” he said from Iowa, where he was presenting at the state’s two major universities. “You have to stand up to them, you can’t be afraid of them. And when they rear their ugly head, you have to do everything to stamp them out, instead of giving them a wink or a nod like Trump does.”

In a previous interview with The Gazette, Stallworth spoke at length about his mother, a single parent who “raised me to not take any crap from anyone who called me a n—–.” This led to three fights growing up in El Paso, he recalled. By the time he moved to the Springs in 1972, joining the police force as a cadet, he considered himself “a nonconformist at heart.”

He still considers himself that. He’s still the same, he insisted, unchanged by the movie’s success.

“I don’t consider myself a celebrity,” he said. “I’ve been labeled a hero by some, and I definitely, definitely don’t consider myself a hero. I was just a cop who had a job to do.”