BIDLACK | The evils of an activist Supreme Court?

Everyone is entitled to their own opinion. And if you are one of a very special group of nine folks in Washington D.C., you are entitled to a legal opinion. Such opinions, from the nice men and women in the black robes in that big marble building with the “Supreme Court” sign out front, effectively carry the power of law, as they interpret the Constitution in the 21st Century. One thing we all agree on is that we like the court’s rulings when we agree with them, and we are unhappy with these jurists when we disagree.

And when we disagree, the charge of “judicial activism” often rings out. But how do we get there? Well, the Supreme Court of the United States usually (at least 90% or so in even the most “active” SCOTUS sessions) embraces the legal doctrine of “stare decisis” which literally means “to stand by things decided” and which practically means, be guided by the previous decisions of the court, absent some new and compelling reason for a change. And, as lower courts are largely bound by SCOTUS rules, this doctrine trickles down throughout the judiciary. Not too bad an explanation for a non-lawyer, eh?

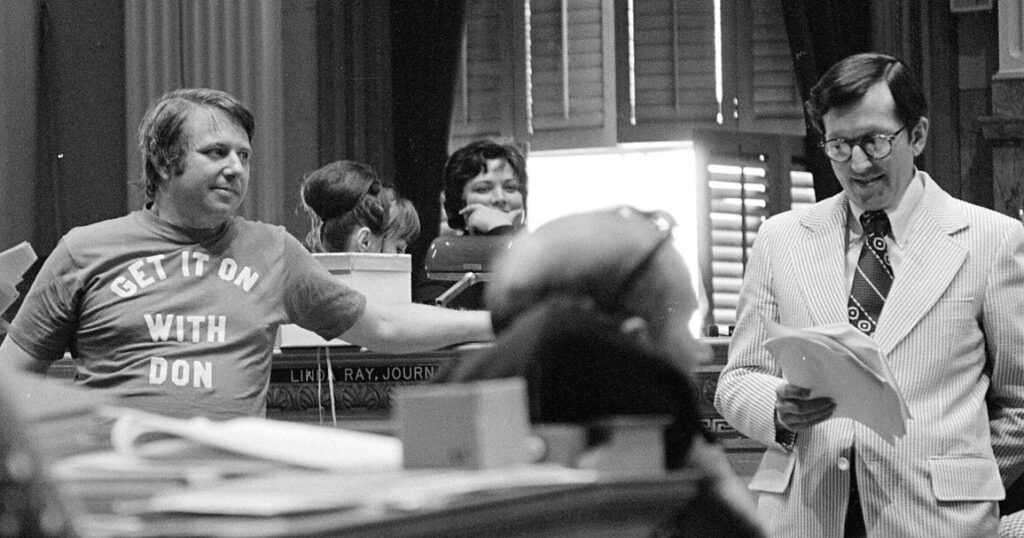

The passing of a legend, Linda Brown, last week, got me to thinking about this issue of activism and what it really means. This then-little girl in Topeka, Kansas changed the nation profoundly, and we are in her debt for her bravery and character. That is because, from time to time, there needs to be a fundamental change in the law, or at least how the law is interpreted, breaking with historical precedent. From Brown v. Board of Education and Marbury v. Madison to Gideon v Wainwright and District of Columbia v. Heller, the SCOTUS has broken with stare decisis when the members felt it important to fix a profound and historic wrong. Chances are, you agree with some of their decisions and disagree with others, but for lots of folks, when they disagree, they often cry “activists!”

I suggest that the term, activist court, should be more non-political, and should reflect what it actually means – breaking with precedent. Now, in cases like Brown, few would now argue that the Court decided wrongly. Led by the brilliant and underappreciated Thurgood Marshall, the Brown legal team convinced the SCOTUS that, as Chief Justice Warren wrote for a unanimous Court, “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” This was a dose of judicial activism to be sure, and it was a break with the doctrine of stare decisis but is was the right thing to do – judicial activism in the cause of justice.

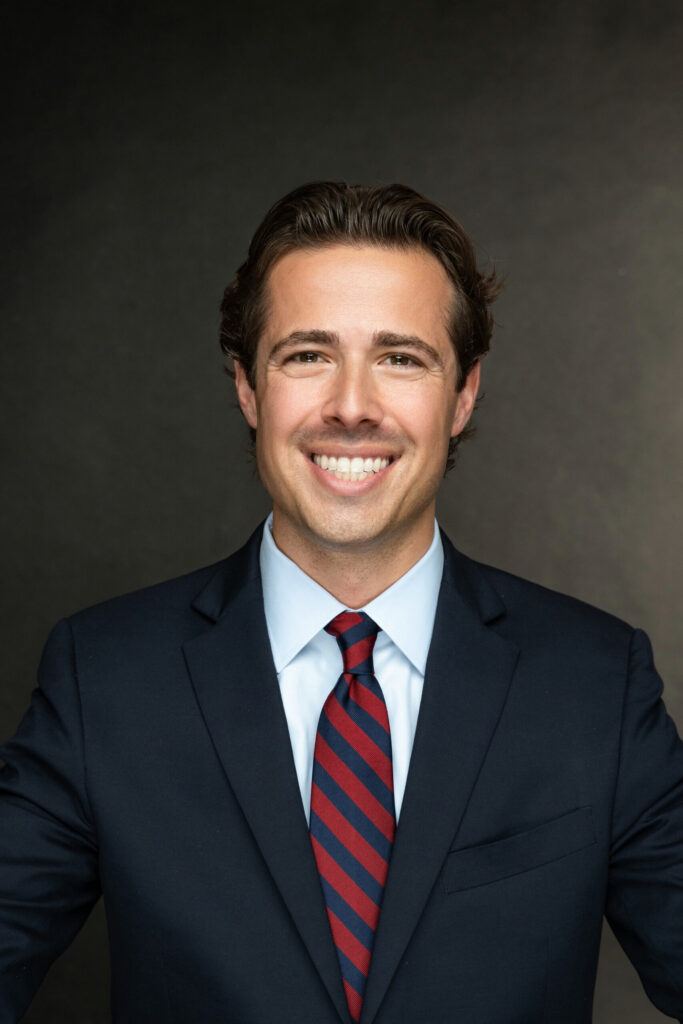

Today, as I hinted above, the charge of activism is often a pejorative, implying a failure to honor our nation’s core values. But this is nonsense. Judicial activism, when it rules in your favor, is the righting of a historic wrong. When it goes against you, it is judicial overreach and vile. Those on the right are more commonly expressing outrage at activism than those on the left, but there is enough insincerity on this subject to go around. But I do recall, for example, in my own congressional run back in 2008, that my opponent, a sitting GOP Congressman, traditionally the champion of “small government” and limited federal reach, argued for a government with enough size and scope to ensure that no single-sex couples were getting married by local government authorities. Hmm… Overreach?

In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in the famous Citizens United case, that the federal law restricting and regulating political spending by corporations and unions was unconstitutional. In doing so, the Justices in the majority overturned not one but two previous SCOTUS precedents going back decades. Your own politics can help you decide if this was a good or a bad thing (hint: it was a bad thing), but there is no denying that the current Court punted stare decisis to the curb and invented what might be called new law out of whole cloth.

So, I applaud the Court when it is activist in Brown and other such cases with which I agree, and I condemn the Court for Citizens and Heller and other cases where they were, well, wrong (from my biased and non-lawyer perspective).

There is no simple and correct way to look at judicial activism either in the Supreme Court of the U.S. or of Colorado. We hope the members of both Courts will act honorably and within the legal boundaries of our system, but when they do not, from one point of view, I encourage you to yell “you’re wrong” rather “judicial activist!”