A lifeline inside and outside the courtroom: Colorado’s newly minted legal workers step into arena | COVER STORY

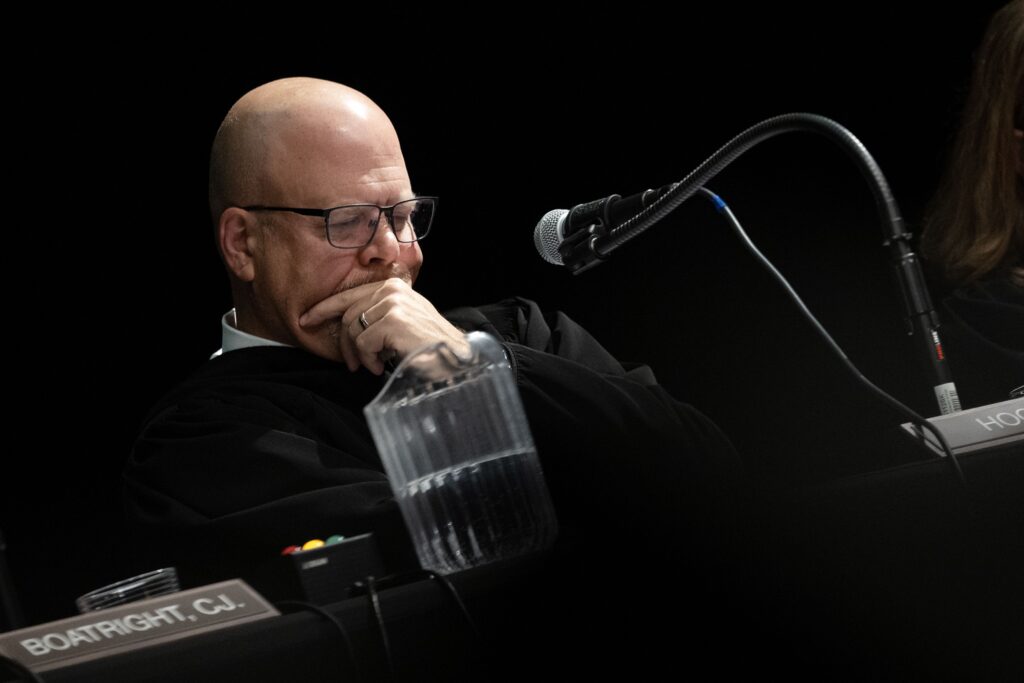

Last month, Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright looked out at the packed courtroom of the Colorado Supreme Court to usher in a historic moment in the state’s 148-year existence.

“We are at a point where people need help. And we’re calling in the cavalry,” he said.

Boatright proceeded to swear in the first class of licensed legal paraprofessionals — 58 women and one man who will be trailblazers in a new legal occupation. More than a paralegal but not an attorney, LLPs are authorized to practice law in limited fashion. They will represent clients and appear in court in family law cases, where roughly 75% of parties currently are unrepresented.

Justice Melissa Hart, delivering the keynote address at the June 20 swearing-in ceremony, noted the heavy lift required to will the LLPs into existence, changing ethics rules and rules of civil procedure to persuading the legislature to amend Colorado law. She framed the creation of the LLP program as an access-to-justice issue for litigants navigating high-stakes cases from child custody to divorce.

“We need solutions to help middle class people, lower-income people, obtain legal advice and the emotional support, practical support they need as they navigate that process,” Hart said.

Referring to the state’s highest court, she added: “We have you backs. We’re here to support you.”

Colorado Supreme Court Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright gives opening remarks during a swearing-in ceremony for the first-ever class of licensed legal paraprofessionals, a newly authorized occupation allowed to practice law to a limited extent. The LLPs took an oath of office in the Colorado Supreme Court’s courtroom on Thursday, June 20, 2024. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Chelsea Deeder, a paralegal with Lyons Gaddis in Longmont, said she was motivated to become an LLP to avoid the debt that comes with law school, while being able to step up her involvement in domestic cases. Deeder anticipated being able to help clients avoid court in mentally draining family disputes.

“It’s been a lot. My husband has been taking care of our kids while I study and do these classes,” she said, standing near her young children. “It’s pretty cool to be one of the first.”

***

The following morning, dozens of the new LLPs gathered in a meeting room across the street at the headquarters of the Colorado Bar Association. With topics ranging from client intake and substantive law, current and former judges prepped them on how to act in the courtroom — and how to stay out of it, if possible.

“One of the dangers that I want to make sure you’re aware of, for your clients’ sake, about why not only is settlement better for people,” said Angela R. Arkin, a retired judge from the 18th Judicial District and the chair of the Supreme Court’s LLP committee, “but being judged — that stranger in a black robe deciding your future, your children’s future, your finances?”

“Oh, my goodness, that’s harsh. That’s painful. It’s very, very rare that your client’s gonna walk out of the courtroom, hug you and say, ‘I’m so glad I paid you so much for that horrible thing that just happened to me,'” Arkin said.

Fighting for respect

As of May 2023, five states had active licensed legal paraprofessional programs, with eight more states in the pipeline. When Colorado’s Supreme Court green-lit the LLP framework last March, the director of the state’s Access to Justice Commission called the initiative “the future of modern practice of law.”

However, progress has not been uniform.

Washington, which adopted the first LLP program in 2012, canceled it in 2020 after the state Supreme Court voted, 7-2, citing a “small number of interested individuals” and the “overall costs of sustaining the program.” A subsequent report by the Stanford Center on the Legal Profession called those justifications into question, pointing to hostility from Washington’s bar association and turnover on the Supreme Court as more plausible reasons.

“Luckily, we are in a different situation, as you can see how thrilled our entire Supreme Court was with you all becoming members of the bar yesterday,” said Arkin.

Jefferson County Magistrate Marianne Tims, who was in the audience, quoted from a text message Boatright sent her, calling the LLP swearing-in “one of the few fun things I’ve done as chief.”

“So, just remember that when you’re getting pushback,” Tims told the paraprofessionals.

Chelsea Deeder sits with her son, Rider, 4, as she and and other graduates of the first-ever class of licensed legal paraprofessionals, a newly authorized occupation allowed to practice law to a limited extent, swear an oath of office in the Colorado Supreme Court’s courtroom on Thursday, June 20, 2024. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Colorado’s LLPs heard from three of their counterparts in other states. One LLP in Washington, who is still allowed to practice despite the state Supreme Court sunsetting the program, said she is normally not allowed to sit with clients or talk to them during trial. But after an attorney opposing her had no issue with her moving to counsel table, the judge permitted her to do so — a sign that relationships are mellowing.

Stephanie D. Villalobos, a paraprofessional in Arizona, said in contrast that some attorneys engaged in bullying and caused her to question her competency.

“Just know that you know what you’re doing. You passed exams. You’re sworn in now. Everyone is not gonna be in support of it. They’re just not,” she said.

Speaking to Colorado Politics after the training, Arkin demurred when asked if the belittling of LLPs may stem from the fact that approximately 85% of paralegals — the dominant path to the profession — are women. She believed the newness of the licensure and the lesser amount of formal education required played a larger role in the differential treatment.

“They’re very smart, they’re knowledgeable, they’re capable,” Arkin explained. “But there are folks who think they’re better than other folks.”

A’s, B’s and C’s of being an LLP

The Colorado Supreme Court’s rules for LLPs contain nearly three pages describing what paraprofessionals can and cannot do with their limited law license. They cannot handle matters of disputed common law marriages, expert testimony for the valuation of complex assets or the examination of witnesses. They can make opening and closing statements, address the court, review and file documents, advocate for a client in negotiations, explain court orders and advise a client when a lawyer would need to handle certain aspects of a case.

Although judges have been receiving education about the paraprofessionals, presenters stressed to the LLPs the danger of overstepping their listed responsibilities, even when they are being pushed to do so in court.

“I can envision a judge who is overwhelmed or doesn’t really like domestic relations say, ‘Just ask questions of the witnesses. We only have an hour. We have to get through this case,'” said Tims, the Jeffco magistrate. “You have to be able to say, ‘I can’t do that.’ And that’s a really difficult situation for you to be in. But if you exceed your authority because a judge asks you to, your license is on the line, not that judge’s.”

Multiple speakers suggested LLPs carry a “bench card” — a reference card to show judges outlining the parameters of paraprofessionals’ abilities. But some also emphasized LLPs can be in as equally powerful a position as attorneys to shape outcomes for their clients.

Angela R. Arkin, who helped develop Colorado’s licensed legal paraprofessional program, stands outside the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law on June 28, 2024.

The Supreme Court set up two paths to becoming a licensed legal paraprofessional. The first entails a combination of higher education, plus 1,500 hours of law-related experience, including 500 hours of family law. The second path requires 4,500 hours of law experience within the last five years, plus 500 hours in family law.

The licensure also involves two exams, one in ethics and one in family law.

“The ethics portion was brand-new information,” said Alexia Smith of the firm Goodspeed Merrill in Englewood, who estimated she knew 99% of the family law content from her years as a paralegal. She added that while other LLPs’ experiences varied with the law firms where they worked, her attorney, Angie Whitford, provided multiple levels of support.

“Angie advocated for the firm to cover my application fee, they covered my ethics course fee, they covered my family law (class) fee. Each of those classes were $750,” Smith said. “She gave me two weeks off before the exam to really study and make sure that I was as prepared as I could possibly be. And even probably about two weeks before, started to try and lighten my load as far as what she was assigning to me.”

Darla Junger, one of two LLPs working at the Woody Law Firm in Denver and who became a paralegal after her own contentious divorce, said the 59-person class created several smaller groups to support each other during the brand-new process.

“I think the one takeaway that I’ve gotten over the last couple of weeks is just how much the LLPs that were sworn in wanted to be successful,” she said. “I really feel that we as a group will work well together.”

The oath for Colorado’s licensed legal paraprofessionals.

Business model

A key motivator of the paraprofessional program was the recognition that many litigants in domestic relations cases struggle to afford an attorney, whose rates can exceed $300 per hour. In Washington, by contrast, paraprofessional billing averaged around $160 an hour.

More than five decades ago, law professor William P. Statsky argued that non-lawyers providing services within the justice system was consistent with U.S. history and that contemporary attorneys generally imposed counterproductive limitations on what their non-lawyer assistants could do.

“The presence of these nonprofessional specialists in the marketplace may force lawyers to lower the cost and improve the efficiency of the services they render to their clients in order to meet the competition of these groups,” he wrote in 1971.

Following a 2021 virtual listening tour, the Colorado Access to Justice Commission included the establishment of an LLP program alongside its other recommendations of increased legal aid funding and simplified court forms.

“Based on the experience of licensed paralegals in other states, the Supreme Court anticipates that LLPs will charge one quarter to one half the rates charged by licensed Colorado attorneys,” wrote retired Court of Appeals Judge Daniel M. Taubman, a longtime member of the commission.

Although the commission’s focus was on the lack of access to legal services in rural jurisdictions, the first LLP class does not make progress on that front. More than half of paraprofessionals are working in the Denver metro area with one-quarter in Colorado Springs or Pueblo — likely reflecting the concentration of law firms in the state.

Colorado’s paraprofessionals heard from LLPs in other states who have since set up their own firms, partially due to the forces underlying those programs.

“My cohort, most of us opened our own shops. I think the reason for that is because we had no attorney support,” said Christy Carpenter, a limited license legal technician practicing in Washington.

Although LLPs are technically ready to begin practicing in their existing law firms, several of them acknowledged the rollout will be more gradual, as the concept is still new for the public. “Nurse practitioner, but for law” was the primary analogy suggested for explaining the role.

“As of right now, most of the firms and mine especially, we don’t have any plans in place yet. It was more, let’s get to this point and now we’ll start trying to figure it out,” said Brittany Joerger with Colorado Legal Group in Colorado Springs. “So, for me on Monday, I’m still just a paralegal. Maybe we’ll start finding me some cases at some point.”

Brittany Joerger, a member of Colorado’s first class of licensed legal paraprofessionals, stands in the Colorado Bar Association’s office during an all-day LLP training on June 21, 2024.

Breaking into smaller discussion groups during the training, four LLPs talked with Denver District Court Judge Jennifer B. Torrington about the reality that LLPs will need to pass off certain aspects of cases to lawyers when they reach the boundary of their limited practice. Will an attorney even want to litigate a case in that piecemeal fashion, wondered one LLP.

“It’s really hard to come in as the new attorney and go, ‘Here’s what happened.’ A lot of people won’t take those,” Torrington acknowledged. “Because they want to start right, as they see it, from the beginning.”

Joerger said she envisioned having “just a couple” cases, in which she serves as an LLP but remains a paralegal for other work. Smith, similarly, said she discussed with her supervising attorney how to navigate the division of labor for incoming cases.

On the other hand, some firms have plowed ahead quickly, as Smith said she spoke to another attendee at the training who was already filing a court case as an LLP.

“She was on break like, ‘Oh, I gotta go. I got the client signature back, I gotta go file this now,'” Smith said.

Setting the tone in emotional cases

As much as LLPs heard the nuts and bolts about what they can do to help in a court case, they also received the message that standing before a judge with their client is not necessarily the goal of the program.

“I’m trying to figure out what this family looks like with two people who have no agreement about what this family looks like. I have six hours, at most, to figure that out in a full-day case,” said Arkin, the retired judge. “You’re gonna be so fantastic. But what we wanted you to hear is: Court is not the best use of your amazing talent and skill.”

A panel of mediators advised the LLPs they might be able to use their status as non-attorneys to their advantage when pitching a non-litigation solution in a domestic case. And if the proceedings are destined for court, an LLP can coach their client about not getting themselves ruffled or violating the rules of evidence when presenting information to the judge.

“Again, you can’t be directing the witness. But providing the guidance of, ‘The other party just said a lot of stuff that’s gonna be irritating to you. Remember, you can’t talk about how, well, she cheated on my sister’s whatever,'” said Rebekah Pfahler of Colorado Legal Services. “Pay me a more reasonable rate and I can give you the talk of, ‘I understand that’s frustrating, but that’s not what the court will want to hear.'”

“Attorneys, and now LLPs, really set the tone for what happens in the courtroom. I have seen some hotly, hotly contested cases where the attorneys just tone everything down and it’s because of the way they interact,” said Adams County District Court Judge Rayna Gokli. “So, as LLPs, I would just be aware of the power that you hold as the legal representative in the courtroom to really dictate how that goes.”

The Adams County Justice Center

Professionally, Arkin said there are plans to add an LLP member to the Supreme Court’s advisory committee. Although LLPs can join the Colorado Bar Association, they will not be able to substitute for lawyers on judicial performance or nominating commissions, for example, which allocate slots to attorney members.

If judges, specifically, mistreat LLPs, Arkin said the existing pathways for reporting judicial misconduct will provide a remedy. But she is optimistic the bench will be more understanding due to the timing of the program’s launch.

“LLPs are gonna be coming into a world of judges who might be actually more welcoming and open-minded because they’re newer. Not all of them younger, but newer,” Arkin said.

She added that in contrast to prosecutors and defense attorneys, who take a more well-trodden pathway to the bench, fewer judges arrive with a background in family law. The high proportion of unrepresented litigants creates a further barrier to competent decision-making.

“One of the reasons that we wanted LLPs to be able to be in the courtroom and help judges understand what the issues are is because it’s very challenging to be in a courtroom with no one who can help you understand what these folks are struggling with and unable to resolve,” she said. “If we help judges, we help the people who come in front of them. If judges know what they’re doing, then the public gets good decisions.”