Colorado justices receptive to allowing lawyers to ‘borrow’ allegations from elsewhere

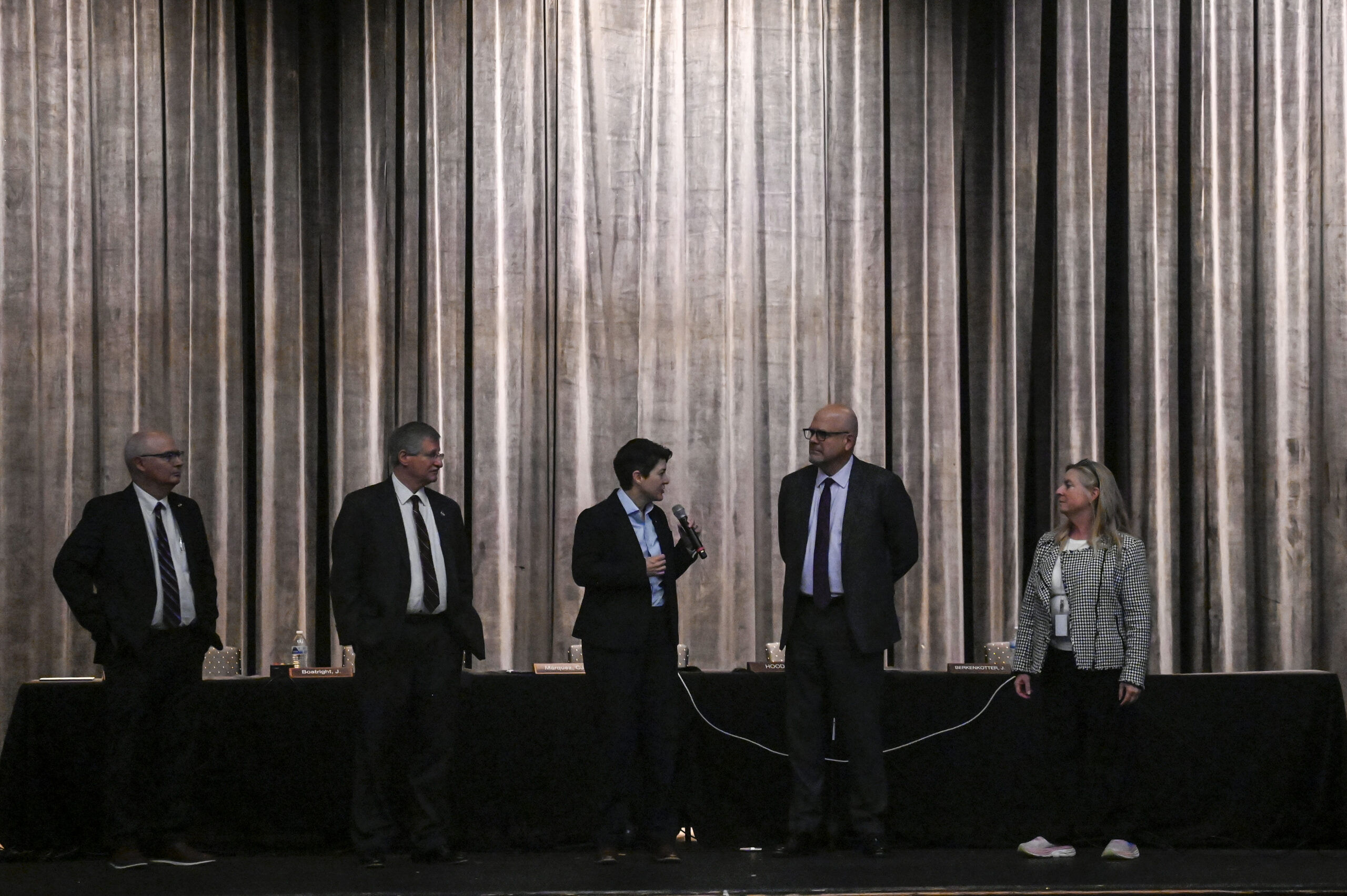

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court seemed open on Tuesday to the idea that plaintiffs’ lawyers can use allegations made elsewhere to bolster their own clients’ claims, so long as the attorney first performs some degree of investigation into the “borrowed” assertions.

Under Colorado’s rules for civil cases, attorneys must attest that the complaints they file are well-grounded in fact to the best of their “knowledge, information, and belief formed after reasonable inquiry.” But what if a lawyer can make their case stronger by importing allegations from other legal proceedings involving the same defendant? Do they have to personally speak with witnesses — who may be unnamed or confidential — who made the allegations there?

“I think this would be a different case if we had nothing other than quoting some other complaint,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel during oral arguments. “But I express some concern with adopting a black-line rule that says you can never quote a confidential source.”

He added that in many civil lawsuits, the evidence that plaintiffs need to prove their case is in the hands of the defendant or other parties. It could be unreasonable to require a plaintiff’s attorney to re-interview, at the outset, witnesses who provided information about wrongdoing to lawyers in prior cases.

“At some level, there’s only so much plaintiffs can do,” Gabriel said.

Dean Houser sued CenturyLink and its directors based on allegations the telecommunications company violated federal securities law by failing to publicly disclose deceptive charging practices at the time of its merger with Level 3 Communications, Inc.

After a trial judge dismissed Houser’s original complaint and the Court of Appeals reinstated it, Houser amended the lawsuit to include allegations of CenturyLink’s conduct gleaned from multiple states’ attorney general investigations and other litigation. Houser’s attorneys attested they had reviewed federal filings, press releases, earnings calls, media reports and had discussions with lawyers in the other civil proceedings.

After CenturyLink pointed out Houser’s attorneys had imported his allegations from elsewhere, Boulder County District Court Judge Dea M. Lindsey refused to consider those portions of the complaint and she dismissed the lawsuit. But a three-judge Court of Appeals panel decided the practice of “borrowing plausibility” is acceptable so long as some investigation takes place.

The rule mandating that lawyers undertake a reasonable inquiry before making a legal filing “does not require plaintiff’s counsel in such circumstances to speak directly with the confidential witnesses,” wrote Judge Steve Bernard. Instead, the “investigative steps” taken by Houser’s lawyers were sufficient.

The CenturyLink defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing the Court of Appeals had cleared the path for Colorado to become a haven for “copycat” lawsuits that “parrot” allegations lawyers made in other courts.

“This is beyond untenable — it places defendants at the mercy of lawsuits premised on a glorified game of telephone,” argued the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, weighing in to support CenturyLink.

According to the Court of Appeals, “literally, the lawyers in this case can borrow the allegations of lawyers in another case that are not before the court,” Frederick R. Yarger, representing the CenturyLink defendants, told the Supreme Court. “I don’t think it’s ever acceptable to take it on faith from another lawyer.”

“At one end of the spectrum, you could have a plaintiff who basically copies an entire complaint wholesale,” said Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter. “At the other end of the spectrum, you could have a 75-page complaint and there are — pick a number — five paragraphs that are lifted.

“Help me understand how we articulate a rule that would apply in both of those cases,” she said.

Francis A. Bottini, representing Houser, pointed to an Oct. 6 decision of the New York City-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which held that civil complaints may rely on “factual allegations or reports incorporated in complaints from other proceedings.”

“What’s your response to their criticism that you should have seen the actual source or reviewed the source of whatever these confidential witnesses said or the statements they made in the other cases?” Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. asked Bottini.

“I think that’s an impossible standard,” Bottini replied. “The other lawyers aren’t gonna tell you who they are because it’s their source. They’re worried it will scare them off.”

Yarger acknowledged that “in some cases” there could be independent sources that validate a plaintiffs’ allegations. Reviewing the original source materials or corroborating documents would likely be necessary before an attorney can use that information, he said.

But some things may truly be confidential, observed Gabriel, such as grand jury transcripts.

“There’s only so much a plaintiff’s lawyer can do,” he said.

Justice Melissa Hart did not attend the arguments. She has been on a leave of absence since late October for “family and personal health reasons.“

The case is CenturyLink, Inc. et al. v. Houser.