10th Circuit clarifies when hardship to child can halt parent’s deportation

The Denver-based federal appeals court clarified on Monday that immigration judges, when deciding whether to halt a person’s deportation because of hardship to their child, should consider whether the child meets the age threshold at the time of the decision, even if a significant delay means they are no longer a legal “child.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit addressed the question in an unusual manner. Last year, a three-judge panel concluded the federal government’s interpretation of hardship to a child — with “child” status measured at the time of decision and not the time the evidence is presented — was reasonable.

But within weeks, the U.S. Supreme Court scrapped a longstanding legal doctrine requiring courts to defer to reasonable legal interpretations by federal agencies. Cristina Rangel-Fuentes, whose deportation order was at issue, sought the 10th Circuit’s reconsideration.

The appellate panel, now free to perform its own legal interpretation of the law, nonetheless wound up at the same place.

The law “contemplates assessing a qualifying child’s age when the immigration judge issues a decision,” wrote Judge Nancy L. Moritz in the Sept. 29 opinion.

Case: Rangel-Fuentes v. Bondi

Decided: September 29, 2025

Jurisdiction: Board of Immigration Appeals

Ruling: 2-1

Judges: Nancy L. Moritz (author)

Veronica S. Rossman

Harris L Hartz (dissent)

The question of when to measure a child’s age mattered to Rangel-Fuentes because, had an immigration judge been able to use her son’s age at the time she presented evidence, she would have qualified for the cancelation of her removal to Mexico. But if the immigration judge had to use her son’s age at the time of his decision two years later, her son would no longer meet the definition of “child.”

Under federal law, the government may cancel the deportation of a noncitizen who, among other things, establishes that their removal would “result in exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to a spouse, parent or child who is a legal resident or citizen. “Child,” in turn, refers to someone who is younger than 21 and unmarried.

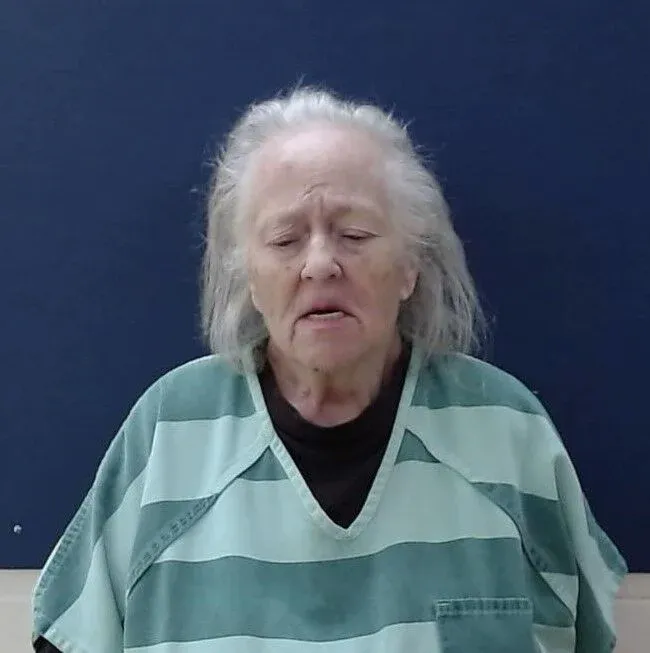

Rangel-Fuentes is a Mexican citizen who entered the U.S. in the mid-1990s. She had three children. In 2014, after the government moved to deport her, she sought to cancel her removal and cited the hardship provision as it applied to her youngest child, who was 17.

In mid-2017, an immigration judge in Colorado held a hearing to evaluate her hardship claim as well as her separate asylum claim. By then, her son was 20 and, legally, a child.

The immigration judge did not issue his decision for two more years. The holdup was due to a federal regulation preventing the government from canceling the removal of more than 4,000 noncitizens in a given year. When the cap is reached, the government must hold off on ruling until the next fiscal year.

By then, Rangel-Fuentes’ son was 22. The immigration judge, therefore, found no hardship existed and Rangel-Fuentes was ineligible to remain in the country. He also rejected her asylum claim. In early 2023, Board of Immigration Appeals member Michael P. Baird upheld the decision, and did not address Rangel-Fuentes’ asylum claim because of how she presented it.

In April 2024, the 10th Circuit panel applied a concept known as “Chevron deference” to the government’s position that a child’s status should be evaluated at the time of decision, even if that decision comes years after a hearing. Because that interpretation of the law was reasonable, the panel concluded it was entitled to Chevron deference.

Then, two months later, the Supreme Court abolished Chevron deference, leading the 10th Circuit panel to reconsider the law’s meaning without giving weight to the government’s interpretation.

“This is a very strange provision, in my view. Because what it should say is, ‘You can’t be removed until your child becomes an adult.’ But it doesn’t,” observed Judge Harris L Hartz during oral arguments in March. “In that context, it seems to me that the important date has to be the date when you order the removal.”

In the opinion, Moritz acknowledged the 4,000-per-year cap forces immigration judges to hold off on issuing orders. Therefore, the law could either require canceling someone’s deportation despite their child turning 21, or else ordering someone deported through circumstances outside their control.

The panel adopted the latter approach.

“We recognize that our interpretation forecloses cancellation for applicants who are eligible when they apply but not when their cases are decided,” Moritz wrote. “But we will not require an immigration judge to don blinders once the record closes and ignore evolving facts that are plainly relevant to an applicant’s eligibility for relief.”

She added that the result was detrimental to Rangel-Fuentes, but “it may favor other applicants.”

Laura Lunn of the Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network, who was not involved in Rangel-Fuentes’ case, said a noncitizen who has a child after their immigration hearing or who marries a new spouse could fall under the hardship provision at the time of a judge’s decision, under the 10th Circuit’s reasoning.

“That said, it could result in inefficiencies in the system because such a change in facts would likely require an additional hearing to allow for new factual findings from an immigration judge for any additional qualifying relatives,” she said.

Lunn added that it will be “interesting to see” how the 10th Circuit approaches other challenges to the government’s views of immigration law, now that Chevron deference does not obligate it to uphold reasonable interpretations.

The re-issued opinion did not alter the previous conclusion by Moritz and Judge Veronica S. Rossman that the Board of Immigration Appeals needed to re-examine and address Rangel-Fuentes’ entitlement to asylum, based on her fear of returning to Mexico. Hartz dissented, calling further examination a “gross waste of time” considering the board’s “horrendous caseload.”

The case is Rangel-Fuentes v. Bondi.