Colorado’s private, often secret justice system exclusively for the wealthy

For nearly two decades Colorado has quietly maintained two judicial systems: One that the public makes use of regularly, and the other a lesser known, almost secret variety relied on by the rich, famous and well-to-do.

Specifically for civil cases — the criminal justice system is unaffected — the systems, on paper, are designed to be virtually identical and indiscernible.

For the most part they are, except for a few key critical differences: One of them allows for the litigants to hire and pay for their own private judge, a retired jurist who earns tens of thousands more dollars than they ever could when their full-time job was on the public bench.

And the cases that end up before a private judge nearly always are conducted off the grid, far from public eyes or scrutiny, ensuring a level of secrecy not afforded to those without the means to pay for it.

A four-month Denver Gazette investigation into the last six years of the state’s appointed judge program, as it is known, found a system that is exclusively used by Colorado’s wealthiest residents to do one thing and to do it privately: get divorced.

What has resulted is a two-tier system of justice, in which those with money and affluence can get faster, more specialized attention, while the vast majority of others are reliant on one that is generally slower and more cumbersome.

Said one lawyer who frequently steers affluent clients to the private judge system: “It’s the difference between staying at the Ritz Carton and the Holiday Inn.”

But the process, as comfy as that sounds, raises concerns of equal justice: “It’s practical that when you pay for something that someone can pay more, so how do I know that justice is really blind in a for-profit business?” said a woman whose divorce case used a private judge and agreed to speak only if her identity was protected for fear of retribution.

“Certain services we don’t want decided by money, and the resolution of disputes is one of them,” said Eli Wald, a law professor at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. “We’d worry that people can purchase justice quicker. It’s just not fair that normal people have to wait so long and those with means can buy resolution faster. In certain things that’s OK, but not justice.”

The range of litigants who have hired a private judge in Colorado ranges from the ultra-famous — including the founder and frontman of the heavy metal rock group Metallica — to the upper crust, such as the former U.S. ambassador to Austria, and the super wealthy, such as the former co-CEO of Chipotle Mexican Grill.

It even includes the political, such as a Douglas County commissioner after having come out as a part of the LGBTQ+ community, and the current deputy attorney general of Colorado.

The newspaper found other troubling aspects of the program, including:

• A system that is virtually a cottage industry, in which the same names of retired judges are regularly appointed and work for the same company. Their average hourly cost — about $450 — is roughly five times what they were paid when they were on the bench and pricier than some of the costliest divorce lawyers.

• A rubber-stamp process, where the chief justice of Colorado’s Supreme Court — the sole authority to make the judicial appointments — has never denied a request and, in several cases, not bothered to check whether the appointed judge had any discipline or complaints against them.

• There is virtually no oversight or review. When litigants request the appointment of a private judge to their case, the wording is so outdated that prospective judges agree to abide by rules of judicial conduct that haven’t existed for more than 15 years — errors that are frequently repeated in the chief justice’s appointment order.

• A greater frequency of cases that are suppressed from public access, a measure of secrecy that includes the appointed judge’s order to do so and the lawyers’ underlying request for it. One private judge has sealed about two-thirds of the more than three dozen cases she’s been appointed to handle since 2019, a frequency far more than she ever suppressed in her years as a district court judge.

• During their appointments, at least a half-dozen private judges has made political campaign contributions — some of them dozens of times and totaling thousands of dollars. Such donations are prohibited in the Judicial Code of Conduct they agree to uphold.

• Though the rule allowing for private judges was ostensibly created to help alleviate courthouse congestion, the vast majority of the appointment requests said the underlying reason was for the litigants’ personal privacy, even though divorce and civil cases are, by law, presumptively public and accessible.

• None of the private judges except one has filed a personal financial disclosure statement revealing any potential conflicts of interest in the years since they’ve left the bench, even though all other types of jurists are required to do so.

• None of the cases contained a financial accounting of what the private judge was ultimately paid, despite a requirement and oath to do so.

• There is no prohibition on a retired judge with a history of discipline from serving as an appointed judge, despite such a bar from serving as a senior judge. It’s happened at least once in Colorado.

Half a dozen women interviewed by The Denver Gazette for this article said they’d never heard of the process until their lawyers recommended it. Several said they felt pressured into agreeing. All refused to be identified publicly for fear their divorces and the lucrative outcomes or custody arrangements they received could be affected, either by the private judge who oversaw them or by ex-spouses they don’t want to anger.

One said she agreed to use a private judge only after her ex-husband’s lawyer warned her that she faced “a long and drawn-out divorce that would leave me penniless.”

Another said she felt the system was little more than “a money grab,” as expenses ran into thousands of dollars more than what had been estimated. It was enough to have liquidated nearly all her savings and left her sleeping in bunkbeds with her children in a small apartment just years after having enjoyed an exclusive home in an affluent neighborhood.

Yet another applauded the process, saying she enjoyed the secrecy away from the public courthouse.

“No one gets to see my dirty laundry hanging out to dry,” she said, adding that she appreciated the additional perks, including “the free lunches they served during the hearings.”

Avoiding the traffic jam of litigation

A private judge has all the power and authority of a regular sitting district court judge. But they are not bogged down by hundreds of cases on their docket and do not answer to voters every few years. Their decisions can be appealed and they are subject to oversight by the Colorado Commission on Judicial Discipline.

Unlike a district court judge, who is paid by taxpayers, a private judge is paid directly by the litigants, who also cover all the other expenses typically borne by the government. The judges can even walk away from a case at any time if the litigants run out of money or fail to pony up funds whenever the judge demands it.

For their part, lawyers who have hired private judges speak of the process glowingly, specifically noting that there is no easier and quicker way to get hearings before a judge, and cases aren’t stuck in a traffic jam of litigation that regularly clogs the public court system.

Among their accolades for private justice, almost universally, the lawyers cite their clients’ nearly guaranteed confidentiality from prying eyes, a benefit most others do not get in regular district court.

That privacy could include a blanket over allegations — unfounded or not — ranging from infidelity, sexual and physical abuse, malfeasance, fraud, or other professional misconduct that could impact reputations, careers and businesses if publicly known.

“We represent many high-end clients who want their privacy, not to have to be in the courthouse and sit on a bench outside the courtroom for all to see them,” said Suzanne Griffiths, an attorney who is among the most prolific employers of private judges. “You can accuse your spouse of all sorts of bad behavior, true or not, and anyone can read it if it’s public record. Private judges are more inclined to suppress a case than a public judge.”

In all, The Denver Gazette found nearly 200 cases involved the use of a private judge since 2019, only one of them a regular civil lawsuit. The rest were domestic relations (DR) cases, nearly all divorces, records show.

“The court system now doesn’t really provide DR cases with sufficient time to handle the high net-worth ones,” attorney Jordan Fox said. “Divorce often needs a more expedient resolution and when we’re doing an even run-of-the-mill divorce, that could easily be a $2-to-$3 million-dollar litigation.”

The solution: a private judge.

“So, when the clients can afford it, going to a private judge with less on their docket and availability at a moment’s notice, it really does provide a benefit,” said Fox, whose law firm, Tate/Sherman & Howard, is a frequent user of the process.

Attorneys point to long delays in scheduling hearings at the regular courthouse and last-minute cancellations that can needlessly cost thousands of dollars for witnesses and experts, as well as thousands more in prep time that has to be repeated for a later date.

“A lot of sitting judges will say when there’s a discovery dispute, they don’t want motions, to call their office, maybe it happens sooner, but frequently not. You might not get the time you need,” said attorney Jersey Green, who litigated the only civil case to use a private judge. “They’re just not available and don’t have the time and can be extraordinarily frustrating. So, a case with hundreds of small skirmishes, potentially, there’s not a real efficient way to handle it in the traditional court context.”

‘It’s where the money is’

The Colorado General Assembly in March approved a Judicial Department request to add a dozen more district court judges in answer to a system it says is so overburdened that it can’t keep up.

In an analysis the department made of judicial workloads, it noted that, even though the number of domestic relations cases statewide dropped by more than 3,300 in 2023 compared to five years earlier, there’s been a greater need for judges to work on them.

Yet, The Denver Gazette found that many of the counties where the new judges are to be allocated aren’t the ones where the most private judge appointments are happening, theoretically the places with the most crowded dockets.

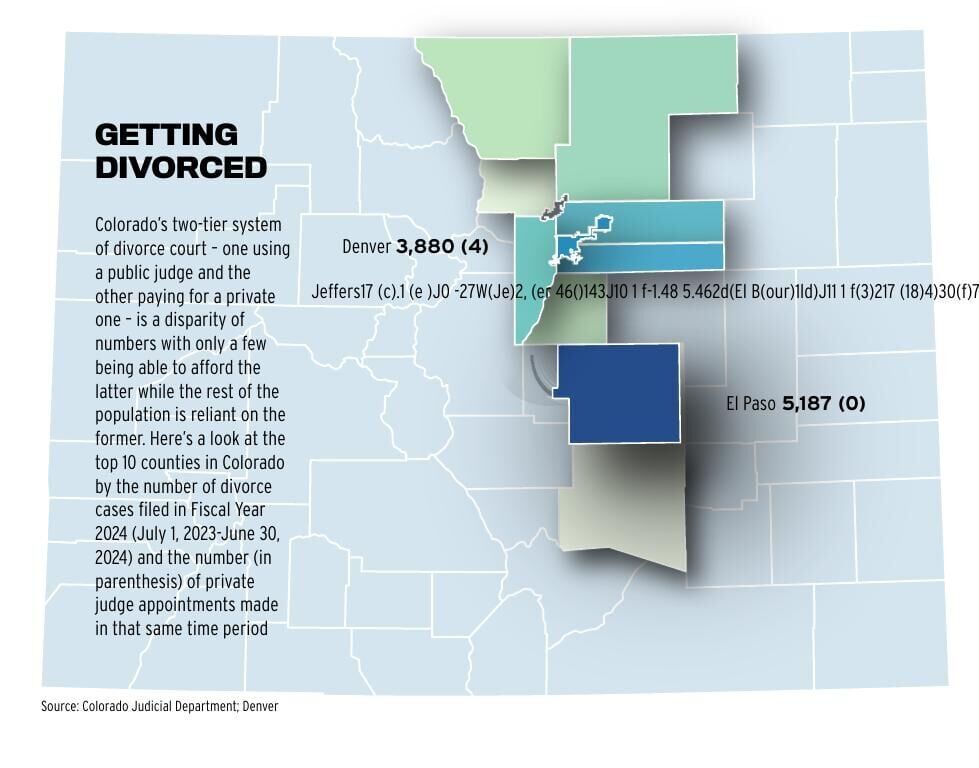

For example, El Paso County and the 4th Judicial District in which it sits has by far the highest number of domestic relations cases filed annually, with more than 5,440 of them in 2023, according to the Judicial Department’s annual report.

Only five private judge appointments have occurred there in the past six years, The Denver Gazette found.

Denver had the second highest number of divorce filings last year and accounted for a quarter of the private judge appointments, but no new judges are allocated there.

The two counties with the most private judge appointments — Arapahoe and Douglas, respectively — accounted for a third of them, records show, jurisdictions that ranked third and seventh in the state for domestic relations filings last year. Only one new judge is allocated for the two judicial districts in which they sit: The 18th and 23rd.

Some of the other counties with the greatest number of DR case filings — Weld, Larimer and Pueblo among them — have had no private judge cases the past six years, records show. Of the three, one new judge is being allocated to Weld County’s 19th Judicial District.

“We do not currently have enough active judges to handle the workload of the courts. The senior judge program, appointed judges … and retired judges all help expand our capacity to serve the public by resolving disputes in a timely and efficient manner when the court system is understaffed,” the Judicial Department told The Denver Gazette in an email through a spokesperson. “But even those additions are far from sufficient to address our need. The contributions of our retired judges, whether provided through the Senior Judge Program or paid for by the parties in a civil matter, are critical to assisting our active judges in meeting the public’s needs.”

And Eagle County, where just 262 divorce cases were filed last year, managed to account for nearly 5% of all private judge appointments since 2019, records show.

Similarly, Boulder County saw more than 1,100 divorce cases filed last year and has had more than 8% of the private judge appointments happen there.

Neither judicial district is scheduled to get a new district court judge.

Said a retired judge who asked her name not be used in order to speak freely: “Clearly, it’s not where the need is; it’s where the money is.”

The judge has not received an appointment as a private judge, though she said she would if asked.

“This private judge system is a godsend to them and they can probably name their price,” the retired judge said about the hourly rate a private judge is paid. “It’s an extremely lucrative practice.”

Adapting rules for private judges

Colorado’s private judge program was on the books in the early 1980s but rarely used, largely because the Supreme Court hadn’t bothered to come up with any rules for how it would operate. It remained in obscurity.

Although then Chief Justice Anthony Vollack issued a directive in 1996 regarding appointed judges, it didn’t change much. Of particular note was that any appointed judge would be paid an agreed upon salary, a change from an earlier and less popular practice of paying the same as any other district court judge. Apparently not enough retired judges said they’d be happy to help.

Despite the order, use of private judges remained rare.

That shifted in 2004 with the court’s formulation of a Judicial Advisory Council Subcommittee, which drafted the significant Rule 122 that would govern the selection and use of an appointed judge. With it came a new judicial canon of conduct specifically for those judges.

The Colorado Supreme Court adopted the new rule and the so-called Canon 9 in 2005.

“I think the whole point of the rule at the time was to alleviate pressure on the civil and domestic courts that were groaning because the time to trial was extensive,” said Carol Haller, who was an attorney at Colorado Legal Services, a former Weld County judge and former deputy state court administrator who served on the subcommittee. “This was all a couple of years before we had a push to hire more judges.”

That’s how attorney Jonathan Asher remembers it, too.

“There was a sense that for some litigants, the delay and sometimes unpredictability of the court system, that it might make sense to formalize a process that people could ask to appoint private judges,” said Asher, who at the time was executive director of Colorado Legal Services and served on the subcommittee. “It was never viewed as a replacement for the public justice system, merely a supplement that some might be interested in.”

A key difference to Canon 9 that set it apart from the other eight canons other judges were required to follow was the allowance for political contributions. But that ended five years later in 2010, when the Supreme Court adopted a new set of judicial conduct canons that barred appointed judges — as well as senior and retired judges —from making contributions to political candidates and organizations.

Leniency on discipline problems

Colorado’s rules on private judges are similar to those of other states that have allowed the practice for years. California is viewed as the originator of the system, where it is frequently referred to as “rent-a-judge.”

In Colorado, litigants can shop around for a retired judge whose schedule — or lack of a busy one — could accommodate their need to move things quickly. Sometimes, that’s a matter of finding a judge with a degree of expertise in a particular subject area, such as family law.

A frequent criticism of the public courts is that litigants are at the mercy of the public docket, and often of judges who are unfamiliar with the complexities of family law. With a private judge, hearings are at the convenience of the litigants, not the judge.

But there are critical differences, too. In Texas, for example, a private judge must meet certain criteria in order to be appointed. One area is that the candidate must not have been removed from office or resigned while under investigation for discipline.

In Colorado, that prohibition applies only to applicants for the Judicial Department’s senior judge program, where a retired judge can work a few months on the bench filling in for other judges, while still earning retirement credits with the state’s pension system.

But not a private appointed judge. There is no prohibition on their service should they have a history of discipline in Colorado — and The Denver Gazette found at least one instance where that has happened.

One judge who retired amid an investigation into their conduct and was later disciplined privately over it has been appointed at least a dozen times, according to records and interviews with people familiar with the matter.

The Judicial Department said a discipline record shouldn’t be an automatic disqualifier.

“Private discipline can be imposed for a variety of reasons that may or may not reflect the judge’s suitability to serve as an appointed judge,” the department said through a spokesperson in an email. “For example, private discipline imposed years ago for conduct that was later corrected should not automatically preclude a retired judge from service as an appointed judge. Consideration of any past discipline should be handled on a case-by-case basis.”

Private disciplines are not public and the Colorado Commission on Judicial Discipline will not confirm any inquiry or outcome that is not a matter of public record.

No discussion about transparency

In California’s system, a retired judge in its senior judge program cannot serve as an appointed one, as well.

“You have to choose one or the other,” California Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald George said in 2002, when he announced the restriction.

It was a question of perception, he said. One senior judge there had put a trial into recess so he could attend to private judging matters.

In Colorado, there is no prohibition on serving both programs. Currently, Randall Arp, who served in Jefferson County’s 1st Judicial District for 17 years until his retirement in 2023, is the only senior judge to have accepted appointments as a private one, The Denver Gazette has found.

“We are not aware of any issues or conflict of interest concerns in Colorado about senior judges also serving as an appointed judge,” the department said through a spokesperson’s email. “Under the Code of Judicial Conduct, all judges must avoid conflicts of interest or appearances of conflicts of interest. At this time, we do not see the need for such a restriction.”

And in California, a private judge is not allowed to suppress or seal any case before them. That decision is left exclusively to the district court judge originally assigned to the case or the sitting chief judge in the jurisdiction the case is filed.

The Judicial Department told The Denver Gazette it has no plans to change how it works in Colorado, which allows private judges to suppress.

In Colorado, where 10 different private judges have suppressed cases from the public, the idea of transparency — or a lack of it — never occurred to the subcommittee that created Rule 122. The one judge who retired amid an investigation into their conduct and was later disciplined privately over it has been appointed at least a dozen times, according to records and interviews with people familiar with the matter.

“I don’t remember any discussion about transparency or appointed judges being a good way for people to have their private business kept private,” Haller said. “No one ever said (in the subcommittee meetings) it was a good way for rich people to keep their business private.”

Asher, who served on the subcommittee, said his concern for the number of suppressions that private judges are approving in Colorado is a matter of perception.

“It would seem to me that if it’s known a particular judge is more willing to seal cases that counsel and litigants, if they think they’ll want things sealed, they’ll try to get that judge hired and approved,” he said. “That just seems logical.”

Few discipline checks

Private judges affirm the chief justice can request their discipline history from the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel that oversees the state’s law licensing and the Commission on Judicial Discipline.

There is no requirement to check, but the thinking is to ensure there are no issues with a judge’s past — or current — performance on the bench before they are appointed. Theoretically, a private judge could still be subject to discipline for any misconduct while serving in that capacity.

“You’d think the litigants would even ask, that one of the attorneys would care,” said Asher of the subcommittee. “I’d be very surprised if neither lawyer would care.”

Yet the frequency with which the Supreme Court staff requested discipline histories is sporadic at best, The Denver Gazette found.

Of the 35 appointments made in 2024, for example, discipline histories were requested only nine times, records show.

The year before it was only four times for the 27 appointments that were made. The same for 2022, records show.

In Texas, a candidate for private judge must not have been removed from office or resigned while under investigation for discipline or removal. That would include their time serving as a private judge in any other matter.

Not in Colorado.

“The standard practice of the Commission (on Judicial Discipline) was to respond to requests for discipline status submitted by the Supreme Court staff and those would include records of past private and public discipline, and any pending discipline or pending proceedings or complaints,” said Christopher Gregory, the former executive director of the commission until January 2024. “Some of those requests that were responded to were in the affirmative.”

Gregory explained that any request for a private judge should include a discipline check no matter how frequently the same name might come up.

“You don’t know if they’re still on the bench and later rotated off, or if there is something new that has arisen since the last request,” Gregory said. “Even if it’s to be the same response, the process requires it be checked.”

The ‘pots and pans division’

The perception that private judging sets up a two-tier system of justice, one for the wealthy and another for the rest, is a long-running discussion.

In Ohio, experts debated the issue in 1995, noting conflicts with the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The amendment “was intended to maintain equality in the treatment of all individuals where state action was involved,” attorney Amy Litkovitz wrote in the Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution. “In the area of private judging, there is some concern that wealthy litigants will be able to hire a private judge, but that litigants who are pro se (represent themselves), using legal aid, or depending on a judgment in order to pay court and attorney’s fees will not. Because private litigants incur expenses which traditional litigants do not, private judging appears more expensive. Thus, the non-affluent are ostensibly excluded.”

Litkovitz, however, thought those problems were “somewhat exaggerated,” theorizing that clearing the clogged courts with private judging actually benefited those forced to use the regular justice system.

Others say private judges, for some litigants, might be compared to expensive shopping.

“When the attorneys develop intimate business relationships with the private judges, and the financial benefits to them both, what’s that look like for the have-nots?” said Christine McGinley, executive director of Project Justice Colorado.

But Colorado, according to one of the writers of Rule 122, relies on the chief justice to weed out any concerns.

However, the chief justice has not denied any of the 177 requests to appoint a private judge in the six years of data reviewed by The Denver Gazette.

“It seems unlikely that the Chief Justice is going to be particularly concerned about the parties motives unless the case is of such notoriety as to arouse the Chief Justice’s curiosity or concern about the desirability of removing the case from the regular judicial system,” then-attorney Richard Holme wrote in The Colorado Lawyer in September 2005, when the new rule was passed.

Said McGinley of Project Justice Colorado, “The more you look into this the more you’ll see it’s little more than a high-end service. The rest of us have to deal with magistrates who start out in DR court without any training on how to even be a judicial officer, let alone an expert in family law. Most if not all new judges start off in family court.”

Some Colorado judges refer to it as the “pots and pans division.”

‘Less scrutiny in private judging’

Public access to the courts is another matter of dispute. Private judging in Colorado is largely, if not exclusively, done in conference rooms or mock courtrooms away from the courthouse.

The subcommittee that issued Rule 122 thought some guarantee of public access was important.

“Since appointed judge proceedings are still public proceedings, a location must be selected that will accommodate the possibility of members of the public or the press being in attendance,” Holme wrote in The Colorado Lawyer. “Thus, it is not expected that a proper location would be the office of one of the lawyers or of the appointed judge. Hearings might be held in hotel or motel ballrooms or conference rooms, school auditoriums, and the like.”

What The Denver Gazette found, however, is that hearings are frequently held in the downtown Denver offices of the Judicial Arbiter Group (JAG), a collection of retired judges who serve as mediators, arbitrators and, for the bulk of the cases in Colorado, private judges.

The JAG offices have a pair of large conference rooms and a pair of mock courtrooms that appear much like public courthouses around the state, except for one key difference: There is no public gallery seating.

Asked about the public’s ability to access any hearing at its offices at any time, JAG managing arbitrator, retired judge William Meyer, was succinct: “Most of those involve financials and are closed to the public anyway.”

Inaccessibility to hearings that are presumed to be public is a concern, but its impact might actually be less than perceived, according to Wald, the DU law professor.

“In private judging, we allow it not so much because we want the rich and powerful to escape scrutiny and more privacy, we do so because there is relatively little harm to the public,” Wald said. “There is less scrutiny in private judging, but practically speaking the average person is not the recipient of a lot of scrutiny in the first place. There is less of a perception of harm to the public.”

Lack of accounting

The actual costs of the private judge system is a mystery.

Rule 122 requires a public report of the expenses incurred to be filed when the private judge’s tenure ends. But records show that hasn’t happened in the six years reviewed by The Denver Gazette.

That was news to the Judicial Department.

“After the judge’s tenure in the case ends, the parties are solely responsible for filing financial reports that document the amount the parties themselves have spent,” the department said through a spokesperson. “The parties are required to file this information with the trial court, not the Supreme Court. If it is true that this is not happening on a consistent basis, the Department will look into the issue further.”

Each Supreme Court petition to appoint the judge must show how much the judge will be paid — records show on average it is $450 per hour — and estimate the overall cost for all other expenses, such as for court reporters. In Colorado, the chief justice has not denied any of the 177 requests to appoint a private judge in the six years of data reviewed by The Denver Gazette.

At a salary of nearly $199,000 a year, district judges in Colorado are paid about $95 an hour for a typical 40-hour workweek.

The average estimated cost of using a private judge, according to the petitions requesting them, was about $10,000, with several reaching as high as $75,000.

But litigants interviewed by The Denver Gazette said it was much higher with one saying they’d already paid the judge more than $100,000 for a case that is still pending.

“Whenever there’s paid services, there’s always someone who can pay more,” said one litigant whose case is ongoing.

Said another: “The more acrimonious the divorce, the more money they make.”

Editor’s note: The original version of this story said Carol Haller is an attorney at Colorado Legal Services. She was with Colorado Legal Services.