‘A matter of survival’: Charlotte Sweeney explains judges’ attempts to stay ahead of workload at federal court

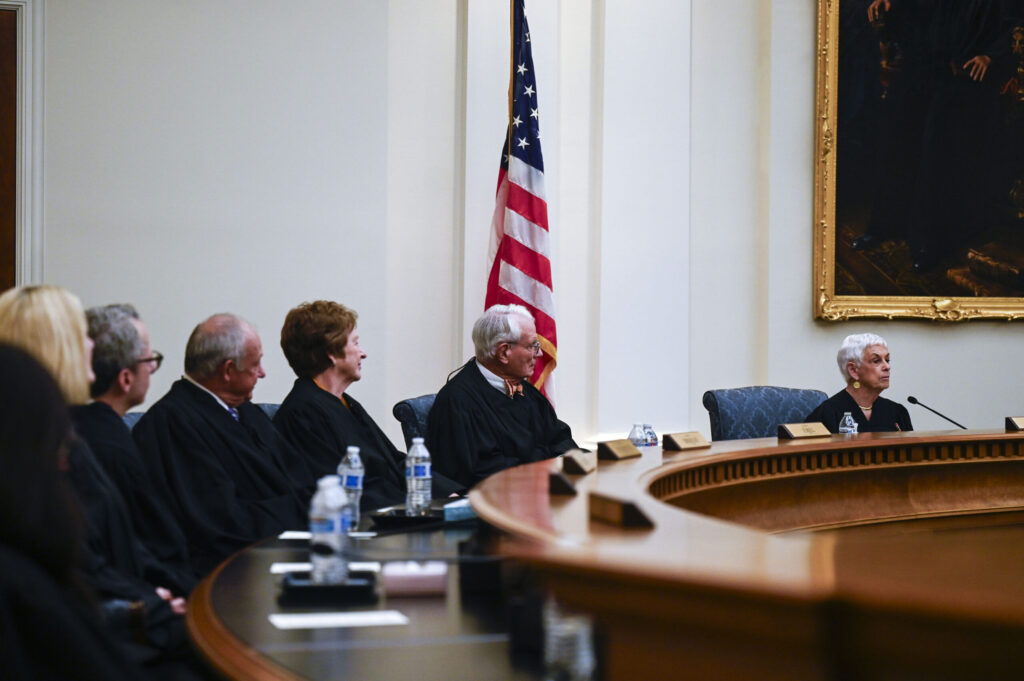

U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney told an audience of lawyers on Wednesday about the reasons judicial decisions may take a long time, what she is doing to fix that, and how Colorado’s federal trial court may respond in the future to bad behavior among some practitioners.

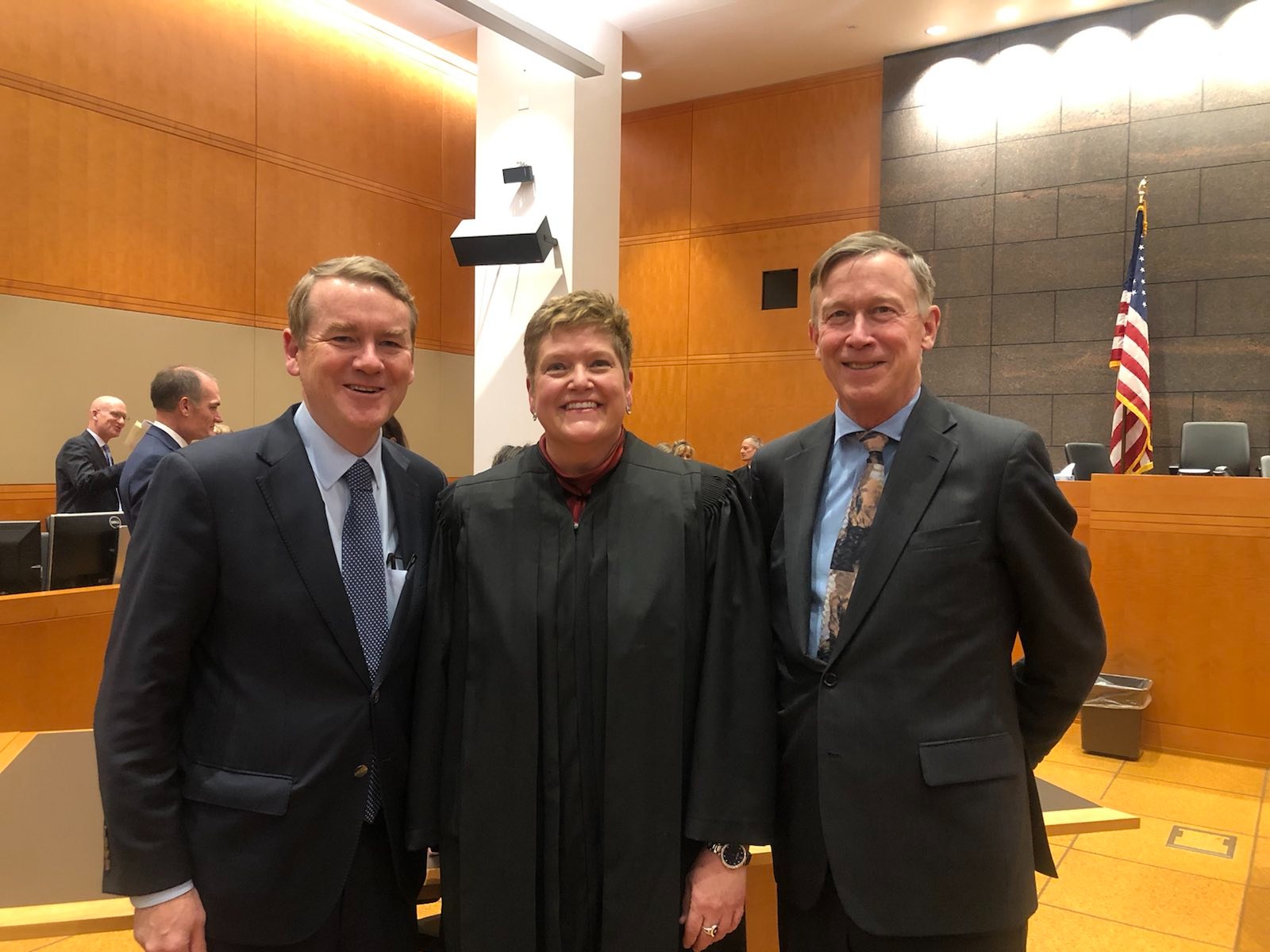

Sweeney also disclosed that further personnel changes at the U.S. District Court might be imminent. Since 2021, President Joe Biden has appointed five of the seven active district judges – including Sweeney – with additional turnover in five of the nine magistrate judge positions.

Sweeney said the most senior magistrate judge, Michael E. Hegarty, will retire at the end of 2024. Hegarty, who was recently appointed the first-ever chief magistrate judge in Colorado, confirmed to Colorado Politics he is “leaning toward” retirement next January.

“If I announce, it will be in the next 10 days or so,” he said in an email.

Sweeney also revealed that multiple, unspecified senior judges – presidentially appointed district judges whose combination of age and years of service permit them to work part time – will fully retire soon.

“You will see that essentially three will be leaving in the next year for good, taking no cases,” she said. “That’s a big change and that’s going to make our dockets even worse.”

The court’s clerk declined to confirm which senior judges, if any, will be departing.

Currently, the court has only one vacancy, triggered by the appointment of former Magistrate Judge S. Kato Crews to the district bench earlier this month. The application period ends in mid-February, after which a merit selection panel will screen candidates and recommend finalists. The district judges will interview the contenders, back to back as a group, and make a decision the same day.

“If you look at our bench, we are amazingly new, both on the magistrate judge level and on the (district judge) level. People aren’t going anywhere for a while now,” she said.

Sweeney added that the most recent three district judges Biden installed were all former magistrate judges. So, if a Colorado lawyer wants to become a magistrate judge, a district judge or potentially both, “this is your best opportunity to be one for a while.”

Delays and their causes

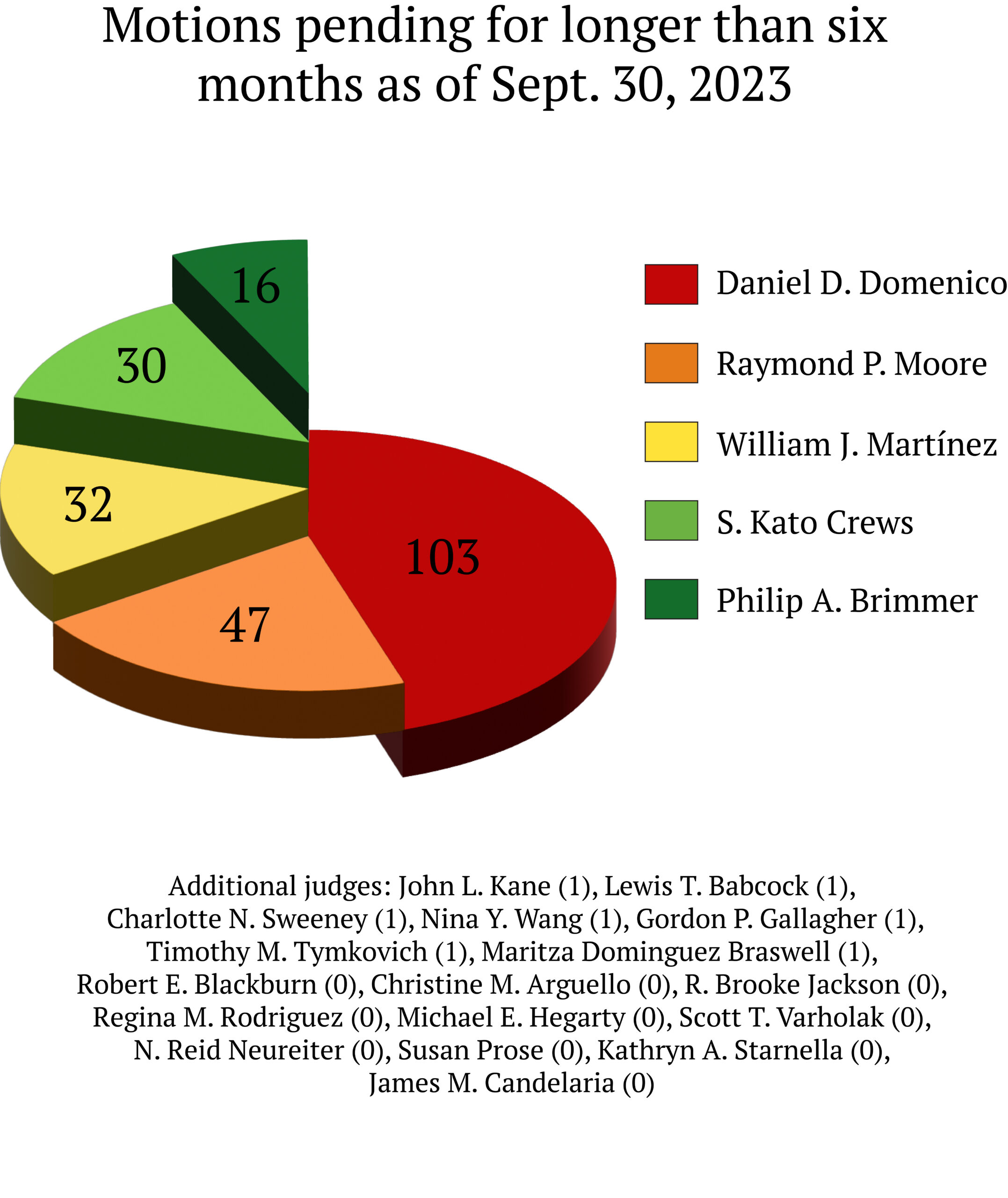

Sweeney addressed recent reporting from Colorado Politics about the small number of district judges in Colorado who persistently take longer to decide motions in civil cases than their colleagues. The data are publicly available thanks to a 1990 transparency requirement that applies to all federal district and magistrate judges.

“If you have a motion pending a long time with me, you are free – this does not apply to any other chambers – you are free to call my chambers and ask for an update,” she said.

Colorado Politics described the experience of multiple attorneys who received an unfriendly reaction after contacting judges who had not decided a motion after months or years. Sweeney suggested the newer judges, who litigated cases more recently in their careers, may be more sympathetic to concerns over delay.

“Yes, the press needs to report how far behind some people are,” she said, “and as I’ve said numerous times, if you get behind, you’re not getting out. And that has happened with a couple of judges over here.”

Sweeney said her preferred mechanism of avoiding a backlog is to schedule a hearing and have the parties argue a motion in her courtroom, after which she may rule from the bench. She said she has successfully persuaded Crews and Judge Gordon P. Gallagher to try out the tactic.

“Sure, I may not sound like a professor,” Sweeney said. But “I don’t care. I want you all to get going and get your answer.”

Some judges, Sweeney added, name-checking Judge Nina Y. Wang, can efficiently churn out written orders. But Sweeney’s preference for oral argument “is how I have decided to keep things moving over here. And it’s mostly a matter of survival to keep ahead of the game. “

A large portion of her time, Sweeney explained, is dedicated to handling criminal cases, which are subject to the constitutional requirement of a speedy trial. Most cases resolve in plea deals, she said, and she spends between three to five hours preparing for sentencing hearings. The federal sentencing guidelines, in turn, are “amazingly complicated,” bordering on “nonsensical.”

“I let anybody speak on behalf of the defendant. This is the worst day of their life. It’s the most important day of their life. If they want 10 family members to speak, I’ll let 10 family members speak,” Sweeney said. “You’re taking away their liberty, and I’m not going to take away their ability to have me consider whatever evidence they want me to consider.”

Factoring in the criminal docket, “it’s like, no wonder all the judges can’t get to our civil motions,” she added. “I’m not whining. We signed up for this job. But it’s important for you to understand the dynamics over here.”

Workflow

Sweeney said she reads everything submitted in a case and, as she does so, thinks about whether she can decide the issue from the bench or through a written order. Besides efficiency, she said another reason for holding oral arguments is to prepare attorneys for speaking in a courtroom should their case go to trial.

“You want to look like it’s not your first time arguing in a court,” she said. “You’ve got to relate to people again.”

To speed up cases, Sweeney advised lawyers to consent to a magistrate judge handling their civil litigation. Although magistrate judges tend to focus on preliminary and administrative matters, they can preside over civil cases entirely on their own if the parties agree.

She also reminded lawyers about a rule – which, to her knowledge, no one has taken advantage of – allowing parties to ask for a magistrate judge to decide a single motion in a case, with an appeal going directly to the federal circuit court.

“I know some people think it’s ‘second tier’ and they want (a district judge),” she said. “It’s nonsense. … I hear tons of complaints about ‘I’ve had this motion pending for two years.’ Well, consent to have the magistrate judge hear it and you’ll be out of there in three months.”

Behavior in the courtroom

Beyond rusty skills in the courtroom, Sweeney also warned about outright poor behavior from lawyers, rising to the level of obstruction or hostility.

“I think what you need to know: Even if it doesn’t seem like we care, I note that and I’m reading it. And it’s like, ‘What’s up with this person?'” she said. “I’m Irish. We have very long memories.”

Much of the misconduct, Sweeney added, appears to come from out-of-state lawyers who do not educate themselves about the rules of Colorado’s district court.

“We may be looking at our own code of conduct here, primarily because of that,” she said.

Otherwise, Sweeney advised attorneys to behave appropriately during trial. In one instance, she saw a lawyer chewing gum while questioning a witness.

“We’re federal court. We’re the formal uncle to state court,” she said. “I tell the story simply to say we’re not overreacting when we say we’re worried about the state of oral advocacy or trial advocacy here. Because you all don’t get to trial very often. We know that. That’s why I’m trying to bring you in for hearings to practice.”

Sweeney also warned lawyers to pay attention to jurors, who she described as more perceptive and less tolerant of tedium than attorneys may think.

“I’ve had to say this: ‘Do you understand how bored your jury is? Do you understand they’re getting angry with you?'” she said. “Civil practitioners have forgotten it’s the jury they’re trying their case to.”

The discussion was sponsored by the Faculty of Federal Advocates.

michael.karlik@coloradopolitics.com