Colorado Supreme Court finds judge wrongly disclosed report about troubled child welfare office

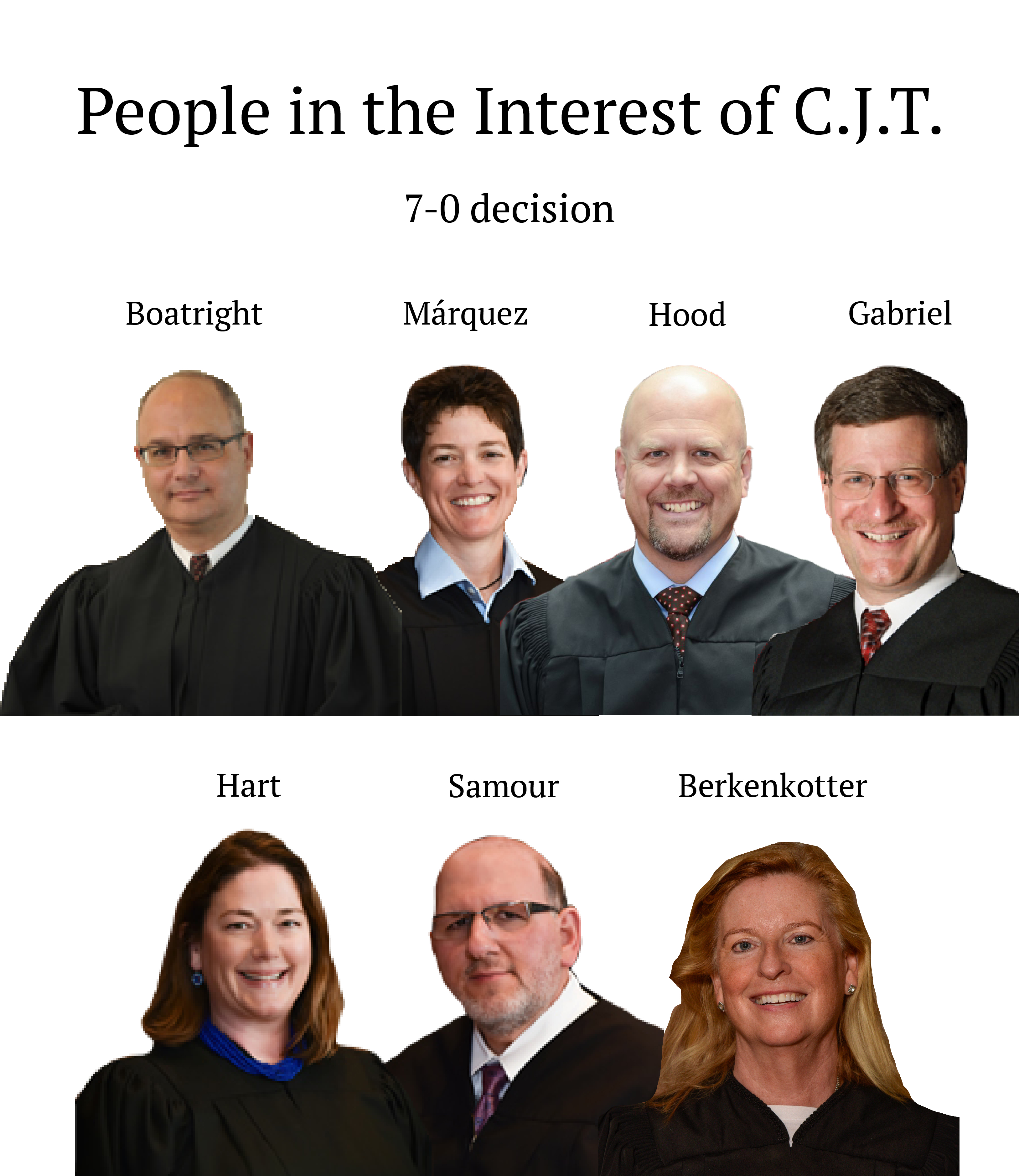

A Washington County judge should not have disclosed a report about potential misconduct in the local child welfare agency to the state office charged with investigating the child protection system, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday.

In addition to finding that District Court Judge Charles M. Hobbs had already given up his jurisdiction over the case and had no grounds to release the report, the justices emphasized the clear boundaries to the Office of the Child Protection Ombudsman’s investigative powers.

The law “does not provide an unlimited grant of authority to the Ombudsman to obtain any and all information that it might deem relevant,” wrote Justice Richard L. Gabriel in the Dec. 4 opinion.

Stephanie Villafuerte, the state’s child protection ombudsman, characterized the decision as narrowly tailored to the facts of the case and indicated her office’s own investigation into Washington County did not hinge on the wrongly disclosed report.

“We had a number of pieces of independent evidence, witnesses and documents that we referred to in that investigation that had nothing to do with the contents of that report,” Villafuerte said. “I think it’s a pretty narrowly written decision based on a series of actions that took place between the state district court, our agency and the county commissioners.”

During the welfare proceedings in the underlying case – involving a child identified as C.J.T. – the board of county commissioners launched an investigation into Washington County’s Department of Human Services and its director at the time, Grant Smith. A small portion of the report, finalized in November 2022, referenced C.J.T.’s case and allegations that Smith was biased against the child’s father and had made a “possible promise” to the foster parents.

The board’s attorney alerted Hobbs, who disclosed a redacted version of the report to C.J.T.’s parents upon their request. The local department then withdrew from the case based on concerns about fairness. No other county welfare agency was willing to step in, so Washington County moved to end the case. In February, Hobbs terminated his jurisdiction.

Around the same time, the ombudsman’s office also became aware of the report and asked Washington County to provide it. The county declined to do so.

In response, the ombudsman’s office filed a motion in C.J.T.’s case – hours after Hobbs had entered his termination order – seeking an unredacted copy of the report. The office argued it needed to understand the effect of any misconduct in Washington County on the child welfare system.

Hobbs granted the request. The board of county commissioners, upon learning of the decision, argued against the ombudsman’s use of C.J.T.’s case to obtain the report. Hobbs reconsidered his ruling and again granted the ombudsman access to the unredacted report, providing it to the office directly.

Washington County then appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

Gabriel, in the court’s opinion, ticked through the unusual sequence of events: The ombudsman’s office, which was not a party to the case, was seeking a confidential document from another non-party, the board, by filing a motion after the trial judge already terminated the proceeding. Under the circumstances, Hobbs had no ability to order disclosure.

Moreover, the Supreme Court emphasized that if the ombudsman’s office wanted the report or documents similar to it in the future, the proper tool was an open records request covering information the law authorized the ombudsman to receive.

“Here, although isolated portions of the Report arguably related to child protection services, the great majority of the Report did not,” Gabriel wrote.

Because Hobbs had already turned the report over to the ombudsman, the Supreme Court ordered the office to destroy all copies of the report and notify Washington County within 14 days.

While the case was on appeal, the child protection ombudsman wrote to the Colorado Department of Human Services to request an audit into Washington County’s department. The office had received its own complaints about bias and legal violations separate from the county’s investigation.

“Specifically, our research suggests that staff of the WCDHS held negative opinions of parents which impacted the WCDHS’ willingness to provide families with the required services and care,” wrote Amanda Pennington, the office’s director of client services. “The CPO is concerned that WCDHS actions may have created unnecessary or prolonged separation of families as well as compromised the safety and well-being of children in Washington County.”

Last month, a spokesperson for the state said it is close to completing its own inquiry into Washington County.

The case is People in the Interest of C.J.T.