87 victims in 94 days: Denver suffered summer of gun violence

Five people were shot in Denver’s Green Valley Ranch neighborhood in two separate incidents over the night of Aug. 12.

Two people were shot in Aurora the same evening.

Two people were killed in a triple shooting in the Five Points neighborhood on Aug. 19.

A month later, five people were wounded in a shooting outside of a bar in LoDo.

The shootings have contributed to a creeping sense that metro Denver is unsafe. Downtown residents, in particular, have complained that criminals seem emboldened, operating without fear of being caught.

They told Denver officials their worries over safety have become “a daily, if not hourly, concern.”

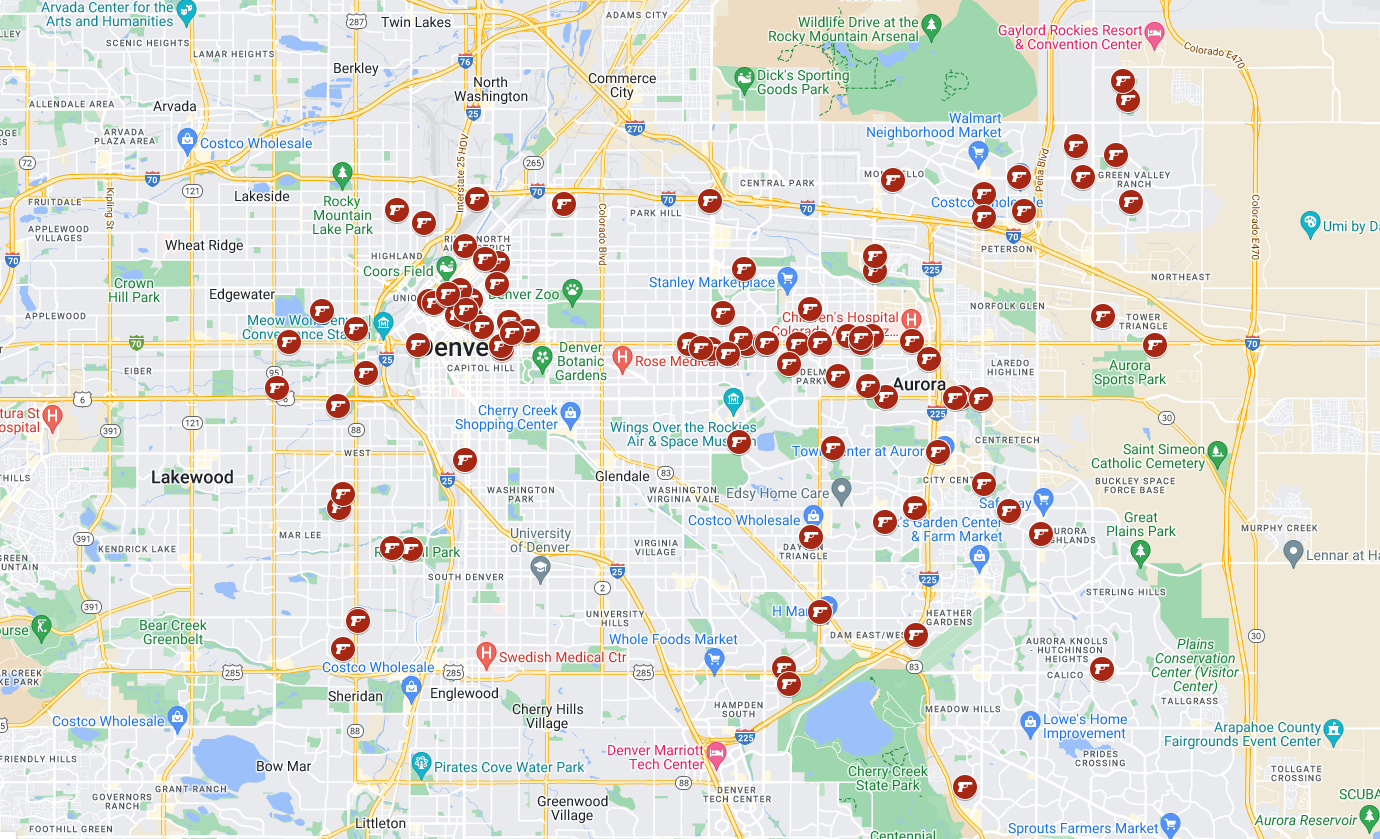

The Denver Gazette tracked 68 shootings in Denver between June 21 and Sept. 23. These shootings involved 87 victims, based on statistics from the Denver Police Department.

Indeed, gun-related violence has continued to spike since 2019. And while the numbers in 2023 are lower compared to last year, they are far higher than the 1993 “Summer of Violence” or in 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The violence has spilled over beyond the summer.

Denver saw 87 shooting victims in 94 days this summer

October had two mass shootings counting more than 12 victims. A shooting at a Halloween party on East 39th Avenue on Oct. 14 left three dead and injured three others. A shooting at a nightclub on East 33rd Avenue on Nov. 5 killed three and injured five.

“We, today, are lightyears ahead of where we were years ago,” said Paul Pazen, a former Denver police chief, noting advances in crime-stopping technology. “Denver should be enjoying the safest time in its history. It’s not.”

A different ‘Summer of Violence’

The “Summer of Violence” – a moniker of Denver media – involved 74 deaths in the metro area in the summer of 1993. Actually, the numbers were not as high as the year prior or after. There were 95 deaths in 1992 and 81 in 1994 and 1995.

But gangs almost entirely fueled the violence that year, and fear began to grip residents when stray bullets hit two babies.

“Crack, guns and gangs were a perfect storm that the media seized upon,” said David Pyrooz, a criminologist and associate professor of sociology at the University of Colorado Boulder. “The wave of gang violence that was sweeping across the city was new. The city didn’t have people getting killed over (gang) colors. Yes, there was gang activity in the 1960s, but the proliferation of firearms and gun violence was new.”

The circumstances in this year’s deadly summer are different. The violence is no longer the sole purview of gangs flying their colors or protecting their turf.

Instead, some of the shootings appeared random, and innocent bystanders have been caught in the crossfire.

All five of the victims in the September LoDo shooting had no connection to Keanna Rosenburgh, the 17-year-old suspect who allegedly shot up a bar after being turned away.

And when a shooting injured 10 people on June 15 – the night the Denver Nuggets clinched their first championship in history – the police said up to six were bystanders.

Thirteen shootings this summer involved more than one victim, according to The Denver Gazette’s investigation. There were 12 during the same time period in 2022.

And the shootings, quite literally, are all over the map, though a majority have been traced to specific neighborhoods – such as LoDo and East Colfax.

“Just because gun violence doesn’t happen in your community doesn’t mean it won’t eventually,” Pyrooz said. “Just because you aren’t fearful, doesn’t mean it’s something you can turn a blind eye to.”

68 shootings, 87 victims

This year’s 68 shootings that injured or claimed the lives of 87 people fell bellow the 83 shootings and 100 victims recorded in Denver during the summer of 2022.

In Aurora, authorities recorded 45 shootings during the same time.

But the number of shootings remains drastically higher than years ago.

In 1993, there were 15 gun-related deaths per 100,000 people in Colorado. That number dropped to 10.9 in 2010. It peaked at 18.2 in 2021, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

The rate of gun deaths hit a 40-year high in 2021, a number that has been steadily rising for 14 years. Nationwide, nearly 48,830 people died from gun-related injuries in 2021, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s a 23% increase from 2019.

Pyrooz, the criminology professor, said the slight decrease in numbers this year still reflects a dramatic high compared to a decade ago. He theorized that coming out of the pandemic and the high-profile death of George Floyd in 2020 might explain that slight decrease.

“All of city governments and institutions just got hit with a double shock between COVID and Floyd,” he said.

He anticipated that, under some kind of a normalcy, crime would go down some more.

“At the start of 2023, we are just starting to get back to more business as usual,” he said.

Officials and others often point to the ease of access to guns in the city as a reason for the increase in gun-related deaths and injuries.

In particular, the police blamed “ghost guns” – weapons that can be built at home and don’t have serial numbers. Colorado banned 3D-printed guns this year.

The spike in the use of “ghost guns” occurred nationwide. A 2023 report from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives said law enforcement confiscated and submitted to ATF 19,273 ghost guns in 2021, a 1,083% increase from 2017.

Between Jan. 1 and Oct. 28 this year, Denver police recovered 1,920 firearms. The police department recovered 1,947 in the same time period last year.

The department’s ShotSpotter technology – an automated system that picks up and reports gunshot sounds in five of the department’s six districts – reported 1,227 gunshots during the summer months, leading to the confiscation of 20 guns and 29 arrests.

The same ShotSpotter data picked up 1,010 shots in the summer of 2022; police seized 23 guns and made 16 arrests.

More guns, more death?

Pazen, the former police chief who is now a fellow with the Common Sense Institute, said the increase in guns is a “chicken and egg” scenario.

Guns don’t necessarily lead to more crime, but the increase in guns is coming from more crime, he said, adding that people are buying guns because they don’t feel safe in their community.

“This increase in gun purchases then led to an increase of guns on the streets because people often left guns unsecure in their cars,” he said. “If people weren’t worried about all the horrible crimes they’re hearing about, they wouldn’t be worried about buying a gun.”

Eileen McCarron, president of Colorado Ceasefire, said the increase in weapons directly correlates to the increase in shootings.

“When there are more guns, there’s more death. It’s that simple,” said McCarron, whose group has been working to prevent gun violence.

McCarron said people began to buy guns before the pandemic lockdown in 2020. She blamed those guns for the increase in violence since 2019, even if, she reiterated, they were not committed by their original purchasers.

Irresponsible and new gun owners may leave their weapons unattended, allowing them to get snatched by “prohibited buyers and youth,” she said.

Pyrooz disagrees that guns are the direct cause of gun violence, but he said that the correlation is fair.

“You flood an area with guns and eventually they will trickle down,” he said.

What’s true, said Denver Chief of Police Ron Thomas, is that an “explosion of the availability of guns” occurred following the pandemic.

Police presence and brazen crimes

Law enforcement officials said they have hunkered down to combat crime.

Denver District Attorney Beth McCann maintained that her office takes gun cases very seriously and prosecutes every case that involves a firearm.

In Denver, the Firearm Assault Shoot Team (FAST) focuses solely on investigating non-fatal shootings, leaving homicides to other teams.

Prior to the creation of FAST, the department distributed nonfatal cases among the officers, leading to investigations that were never finished.

FAST, meanwhile, saw a clearance rate of 60% of nonfatal shootings in 2020, according to data collected by The Marshall Project. While that number dropped to 54% in 2022, Denver still performed better than America’s 20 most-populated cities.

Still, the number of shootings has not significantly gone down.

And the crimes appear to be more brazen.

When 10 people were shot in LoDo following the Nuggets championship win, more than 200 officers had been deployed downtown.

“Cops were a stone’s throw away and someone still decided to pull out a gun and use it,” Thomas said of the incident. “Obviously, just a near presence isn’t enough. We have to do a better job getting guns off the street and getting them out of the hands of people that shouldn’t have them.”

Thomas said partnering with community groups and city councilmembers for gun buyback operations helped get guns off the streets and out of the hands of those that shouldn’t have them – a factor he said is crucial for the police’s efforts to curb gun-related crime.

The city’s buyback operations give people money for turning in guns, people remain anonymous and guns are destroyed on site.

He said the buyback program in 2022 led to around 1,000 guns taken off the street, around half the amount of 1,920 firearms recovered by the department during investigations and arrests between Jan. 1 and Oct. 28 of 2023.

It’s still not enough, Thomas said.

A crisis of culture and policy?

Pyrooz said America’s violence stems from a cultural crisis, not just the amount of weapons.

“Guns are a tool. Someone has to be pulling the trigger,” he said. “There’s a cultural component around norms of conflict resolution that have to be taken into consideration. There’s plenty of countries that have guns, but not as many shootings as us.”

Others, such as McCarron, who agreed with Pyrooz’s assessment, blamed America’s “normalization” of guns. She argued, for example, that the increase in concealed carry permits – initially enacted in Colorado in 2003 – has changed the way people see guns.

“I think it has normalized people just having guns with them all of the time,” she said. “When people get in arguments, they pull out their guns because they have guns. This is a regular part of American society.”

McCann, the district attorney, said it’s “not as simple as more guns and more violence.”

“But it’s easier to have more violence if you have more guns,” she said.

A big part of the problem, she added, is that society is “losing some of those basic respects for life that we’ve always had.” McCann added that social media has played a role in promoting such disrespect for life.

“Kids post pictures of themselves and it’s become a sign of being a man, or growing up, or being cool,” she said. “There’s pressure on social media for people to have guns, particularly among younger people.”

Pazen, the former police official, said the increase in shootings – both fatal and nonfatal – is tied directly to the “weakening of the criminal justice system and tilting of the scales toward suspects and offenders.”

The incarceration rate in 2010 stood at 449 people per 100,000. In 2020, that number dropped to 277.

Meanwhile, authorities recorded 321 violent crimes in Colorado in 2010. There were 423 in 2020.

Even as the incarceration per capita dropped, Pazen noted that Colorado has among the worst recidivism rates in the country, with over 50 percent of people released from prison ending up back behind bars within three years.

“I’m not going to say the answer is that you lock everyone away and throw away the key,” Pazen said. “I’m saying we have to have better outcomes than a 50 percent failure rate for parolees.”

A fix?

Officials, academicians and policymakers agree curbing gun violence among young people is key, noting it’s the same age range that drove the “Summer of Violence” some 30 years ago.

Consider this: Violent crime arrests of juveniles rose to a new 14-year high during the third quarter of 2021, according to the Colorado Bureau of Investigations. Roughly 15 juveniles in 100,000 Coloradans were arrested for crimes of violence.

“It’s not poverty driven; it’s driven by trauma,” Pazen said of the violence among the youth. “When Junior sees big brother involved in violent behavior or is a victim of violent behavior – that is a more likely predictor of future levels of violence. Not whether the person is on public housing, welfare, or anything along those lines.”

Thomas said helping individuals, especially juveniles, find better ways to reduce conflict would directly lead to fewer gun-related incidents. He said he believes avenues exist to identify people at risk of committing gun violence – especially those affiliated with gangs – and find ways to deter crime.

“A lot of the juveniles that engage in gun violence don’t have trusted adults in their lives,” he added, urging police officers and others in the community to step up to become role models for youth.

“They often feel hopeless in terms of their opportunities to have successful futures. That’s something the entire community can help address and make sure they don’t feel like there’s nothing they’re throwing away, nothing they’re destroying by engaging in gun violence,” he said.

But these efforts would take more than just policing, he said.

McCann, who saw an increase in juveniles being tried as adults due to the severity of crimes, said the “next piece” is figuring out “how we change the culture around having to carry a gun to be safe. That’s what we hear from the kids.”

“I do think there needs to be more effort on the prevention side,” she said. “It’s really a community issue.”

Pyrooz called the fight against gun violence a two-stage approach.

“Some people are all about root causes, but you also must do something in the near turn to stop the immediate bleeding,” he said.

He said investing in mental health programs for young people – along with afterschool programs and community centers – can slow down the crime rate in the meantime, and position the state to curb violence in the future.

“These things will pay dividends 10-20 years down the road. We just don’t see it yet. That’s making smart political decisions to invest in communities,” he said.

Pyrooz said to really make a difference, “we need a large collaborative strategy with multiple stakeholders in the community taking part of it. This is not just a law enforcement problem. This is not just a school problem.”

The answer also includes better ways to prevent young people from getting their hands on a firearm, experts and policymakers said.

In Denver, 74% of the 246 juvenile aggravated assault arrests in 2021 involved the use of a firearm.

A survey published in the Journal of the American Medical Association for Pediatrics in March found that one in four Colorado teens said they could get a gun in less than 10 minutes.

Pazen worries about what the immediate future holds.

“At some point, the in-vogue idea of being a Denver resident is going to fade,” Pazen said. “Businesses are going to wonder why they are subjecting their employees to these crime issues. The golden goose is going to stop laying eggs.”

luige.delpuerto@gazette.com