10th Circuit reminds judges: Be attentive to mentally ill litigants

The federal appeals court based in Denver reminded judges last month to be mindful of self-represented litigants who appear to be mentally ill, and to arrange for assistance when required.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit reviewed the appeal of Jessie Tunson-Harrington, whose excessive force and false arrest claims in Adams County were dismissed in the trial court because Tunson-Harrington failed to move his case forward. Tunson-Harrington brought his lawsuit “pro se,” meaning without a lawyer, and repeatedly referenced his stays in Colorado’s state mental hospital during the litigation.

Although the 10th Circuit panel agreed with the decision to toss Tunson-Harrington’s claims, it called attention to the federal rule requiring judges on their own initiative to appoint a legal guardian to protect pro se litigants who lack mental competency.

“We note that the record contains some evidence that Tunson-Harrington may suffer from diagnosed mental-health illnesses,” wrote Judge Gregory A. Phillips in a Sept. 12 order. “Though we think Tunson-Harrington hasn’t presented sufficient evidence to trigger a district court’s mandatory (appointment) duty, we remind district courts to be vigilant to mental-health evidence in cases brought by pro se litigants.”

Case: Tunson-Harrington v. Adams County Sheriff

Decided: September 12, 2023

Jurisdiction: U.S. District Court for Colorado

Ruling: 3-0

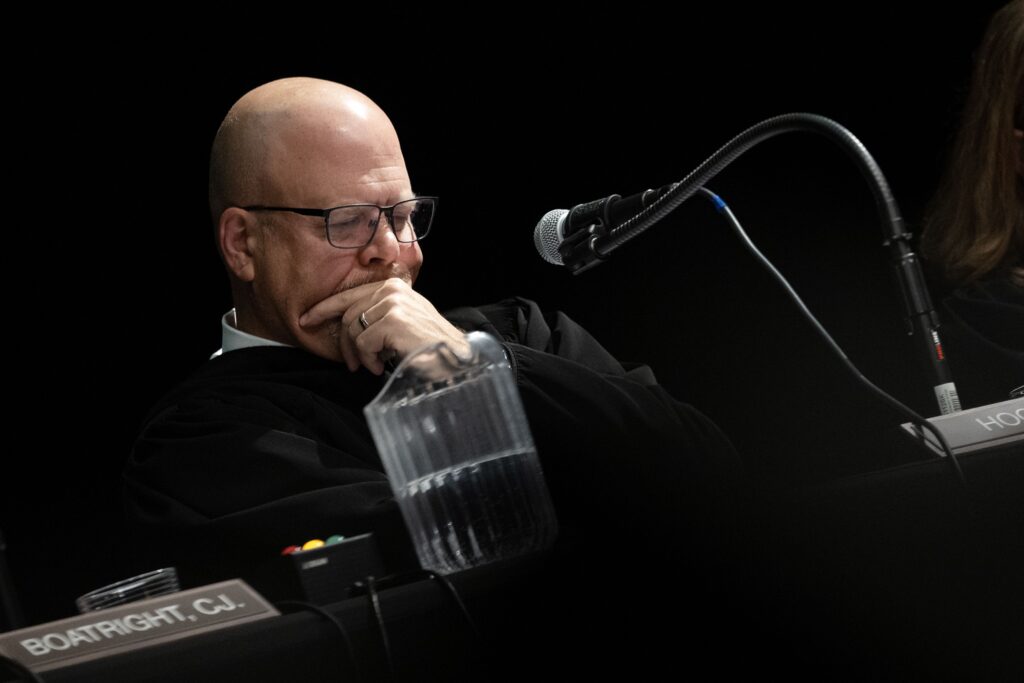

Judges: Gregory A. Phillips (author)

Bobby R. Baldock

Veronica S. Rossman

Tunson-Harrington filed two lawsuits that similarly alleged law enforcement brutalized him in the Adams County jail. He described employees beating, kicking and “lynching” him. He also alleged Aurora police arrested him for a non-existent restraining order violation.

Tunson-Harrington alleged there was surveillance video of his attack by jail deputies, and the defendants conceded they were “involved in an incident” on the day in question. A federal judge authorized the appointment of a volunteer lawyer, which typically occurs when there is merit to the case. However, no attorney agreed to represent Tunson-Harrington.

During the proceedings, Tunson-Harrington filed multiple letters changing his address as he moved to and from the Adams County jail. Specifically, he noted when he arrived at the Colorado Mental Health Insitute in Pueblo.

Eventually, both sets of claims were dismissed after Tunson-Harrington did not take action to move his lawsuit forward and after the court’s mailings were rejected from the addresses he provided.

“The Court is aware of the difficulties faced by pro se litigants who try to navigate the judicial system. This is particularly challenging for an inmate, and it is even more so for an inmate who has mental health issues,” conceded U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson.

“The Court’s patience with the plaintiff’s failure to do anything to prosecute the case (which has also left the defendants in limbo) is coming to an end,” he added.

Tunson-Harrington appealed to the 10th Circuit, arguing he was not to blame for missing the court’s mailings and reiterating that he was in the mental health hospital and deemed incompetent during his case.

The 10th Circuit agreed with Jackson that even with the substantial difficulties incarcerated plaintiffs face in pursuing civil lawsuits on their own, they must “prosecute their cases and follow the court’s rules.”

While it did not find Jackson mishandled the issue, the panel’s order mentioned the federal rule obligating judges to appoint a guardian for a mentally incompetent litigant. Phillips quoted from a recent decision in the Philadelphia-based Third Circuit, where a judge did not explore the plaintiff’s disclosure of his major depression and schizophrenia.

The Third Circuit believed that whenever a judge learns about “verifiable evidence of incompetence,” regardless of whether the litigant has a lawyer, the judge must consider appointing a guardian to act in the person’s interests.

The 10th Circuit’s order did not say what more evidence would have been necessary for Tunson-Harrington to receive a guardian.

The case is Tunson-Harrington v. Adams County Sheriff et al.

michael.karlik@coloradopolitics.com