The 20-minute lifeline: Colorado’s federal court eyes a new program to aid those behind bars | COVER STORY

With nearly two dozen state prisons and multiple federal facilities in Colorado, federal judges routinely hear lawsuits from incarcerated men and women alleging violations of their rights.

The claims range from excessive force and indifference to medical needs to unconstitutional infringements on prisoners’ religious exercise. For the most part, the plaintiffs do not have a lawyer. As a consequence, those lawsuits – which could involve a credible civil rights violation – are more likely to be dismissed.

Now, Colorado’s federal trial court is quietly launching a new project to give those cases more traction.

“It’s been obvious to me since the beginning of the time I became a judge that when prisoners were fortunate enough to get counsel to represent them, cases were handled by the court in a much more efficient manner,” said Kristen L. Mix.

Mix, who retired earlier this month as a federal magistrate judge after 16 years on the bench, had the idea to connect incarcerated plaintiffs who file lawsuits on their own with volunteer lawyers who could answer questions about the legal process. The result is a pilot program the U.S. District Court will commence on Sept. 1.

As envisioned, self-represented, or “pro se,” litigants at one of the state’s prisons – Fremont Correctional Facility – will have the opportunity to submit questions and be eligible for a 20-minute phone call with an attorney to discuss their case.

While there are other initiatives in the federal and state justice systems that enable pro bono lawyers to help litigants with their cases, the 20-minute phone call for incarcerated plaintiffs appears to be a novel method of providing assistance. The phone call is ostensibly a one-time boost to pro se prisoners, but Mix suggested the program has the potential to entice attorneys into offering additional services after getting a sense of what the lawsuit is about.

“A lawyer may talk to a prisoner and think that this prisoner’s case seems to have some merit,” she said. “The lawyer can have an opportunity to look at the case file on the electronic docket, find out everything that’s going on in the case and make a decision about whether a lawyer wants to represent the prisoner.”

David Lane, a civil rights attorney who has represented incarcerated plaintiffs in federal court, praised the program as having the potential to uplift viable cases that otherwise would not have much of a shot.

“A prisoner who is illiterate or semi-literate may have the best claim in the world, but is unable to articulate it in a way that is intelligible. And others may have very weak claims, but they are much better writers,” he said. “Lawyers will undoubtedly stumble upon diamonds in the rough and run with them.”

Many options for pro bono lawyers

Data from the federal courts show that petitions filed by pro se prisoners increased by nearly 19% in Colorado between 2000 and 2019 – and pro se cases of all types rose by more than 35%. But even before the pilot program, options existed for attorneys who wished to assist unrepresented litigants in federal court.

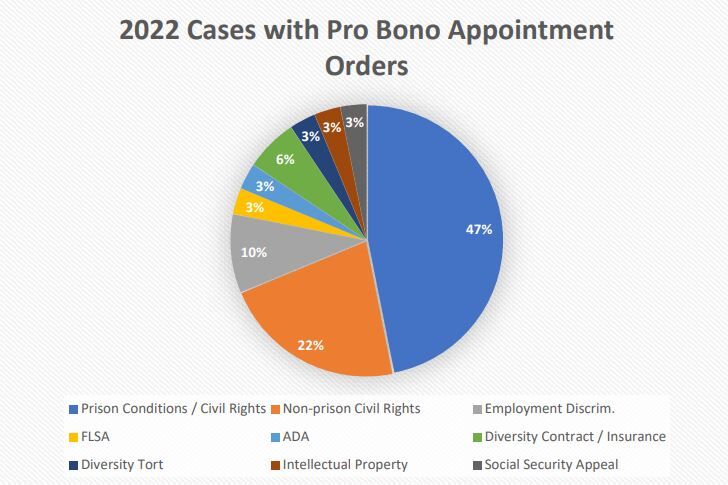

Operated through the Colorado Bar Association, a pro se clinic consults with litigants in person or remotely. In addition, attorneys who have joined the Civil Pro Bono Panel can take on cases after a federal judge determines a litigant’s case merits appointed counsel. In 2022, half of the cases with judges’ appointment orders were prisoner lawsuits.

Other federal trial courts offer assistance programs for pro se litigants, but Colorado Politics could not locate any initiatives exactly like the proposed prison pilot. The Western District of New York, based in Buffalo, has a similar assistance program operated by law students and legal aid organizations – but without the court’s facilitation. The Eastern District of Missouri, in St. Louis, offers 30-minute Zoom appointments to self-represented litigants, although none are currently available.

Annie Skinner, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC), said a U.S. District Court working group asked the department to participate in its pilot program. Fremont Correctional Facility, with a population of nearly 1,500, was the most feasible location based on the amount of lawsuits filed.

“There is no cost to CDOC to participate in the pilot. The court will set up an 800 number, CDOC will add that number to our phone list and the inmates participating in the program will be able to call that number directly,” she said.

Skinner added that calls at the facility are already limited to 20 minutes, and the department will treat the consultations as attorney-client communications, not to be monitored or recorded.

“Since 2012, pro se cases have accounted for over one-third of all civil cases filed in Colorado’s federal court each year,” said Kevin Homiak, a commercial litigation attorney who served on the U.S. District Court’s Pro Se Prisoner Task Force. “While pro se clinics for unrepresented individuals who are not incarcerated are quite common in the federal court system, I am not aware of any program that focuses specifically on increasing access to justice for incarcerated, unrepresented parties in the way that the pilot program does.”

How it will work

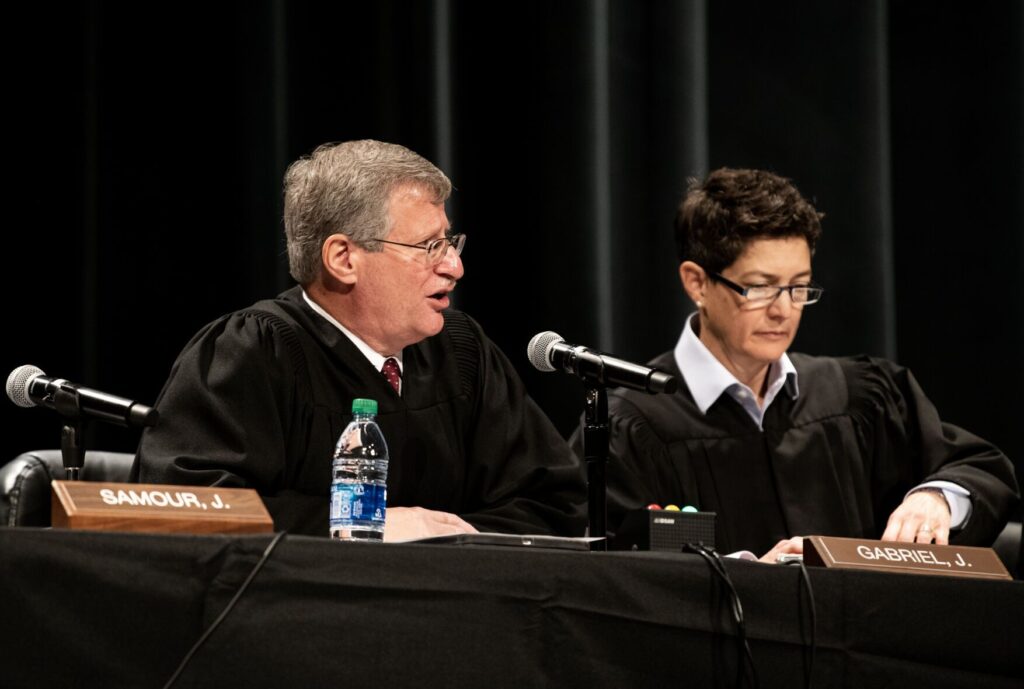

Colorado’s federal court has an intake mechanism to screen pro se prisoner complaints – only 25-30% of which survive that screening, the district court’s clerk estimated. Several law clerks review the cases, along with two judges: U.S. District Court Senior Judge Lewis T. Babcock and a magistrate judge.

Prior to Mix, Gordon P. Gallagher was the assigned magistrate judge until the Biden administration appointed him to a district judgeship this year. In his questionnaire for the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, Gallagher explained his role was to evaluate whether a lawsuit should be dismissed if, for example, it failed to state a claim. Otherwise, the screening could result in an order for the plaintiff to amend their complaint.

The 20-minute phone call is intended for those cases that survive screening and make it onto a judge’s docket. Mix said the idea is for incarcerated plaintiffs to receive guidance on the basic tasks of litigating a civil case: Getting information from the opposing party, serving a witness with a subpoena and otherwise compiling evidence.

“The first positive result is they can end up actually getting a lawyer, but the second positive result is they could learn something about discovery and be able to conduct it more efficiently and effectively,” she said. “And the third positive result is the court can handle the case more efficiently.”

Plaintiffs will need to sign a legal services representation agreement before they participate, and they will submit their questions to a volunteer coordinator.

Colorado Politics requested to see both types of forms, but the U.S. District Court declined to provide them until the start of the pilot program.

Mix, who stepped down from the court on Aug. 4, will be the volunteer coordinator during the pilot program. She anticipates speaking to lawyers about the effectiveness of the initiative, and she also plans to monitor judges’ dockets to assess whether the phone call made any difference in the trajectory of a case.

Some questions – “how much money am I going to win?” – would not be appropriate for the phone call, Mix said. Other questions may be legitimate, but would be better suited for an investigator than an attorney. If a plaintiff’s question is rejected, they can submit another one and still receive their phone call.

But the opportunity is limited to one call per case.

There is nothing preventing a lawyer from continuing to engage with the plaintiff after the phone call is done. An incarcerated litigant may also wish to tell their assigned judge that they are scheduled for a call and ask for an extension of time to respond to the government’s motion to dismiss, for example.

“There’s nothing inappropriate about that. But we don’t intend to have a built-in part of the program that informs the judge that the prisoner has been assigned a volunteer attorney for a 20-minute phone call,” Mix said. “It’s something that happens behind the scenes for the most part.”

There are shortcomings and open questions with the pilot program. Mix acknowledged no incarcerated people had direct input in the development of the program, although judges do hear about the difficulties prisoners have in general in navigating the legal system. The program, starting out, only encompasses one facility and only civil lawsuits that have been drafted and submitted.

“My hope would be that inmates could also get legal help to challenge their convictions when/if appropriate,” said Thomas L. Dybdahl, a former public defender in the District of Columbia who now lives in Boulder. “That kind of program would have another whole set of problems, but it’s something I’d like to see tried.”

Pro se cases are difficult, but not impossible

Convincing a judge or a jury to believe a civil rights violation took place behind bars can itself be a tall feat, but so can getting a lawsuit off the ground to begin with.

Last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit agreed a detainee who a guard allegedly slammed into the ground – with surveillance footage seeming to corroborate that claim – could not bring a lawsuit in the first place because she had filed her grievances with the prison system too quickly.

In May, Mix threw out a lawsuit from an inmate who alleged prison guards failed to protect him from an attack. Her decision hinged on the unrepresented plaintiff’s failure to show the guards knew a “substantial” risk of harm existed, as the law requires.

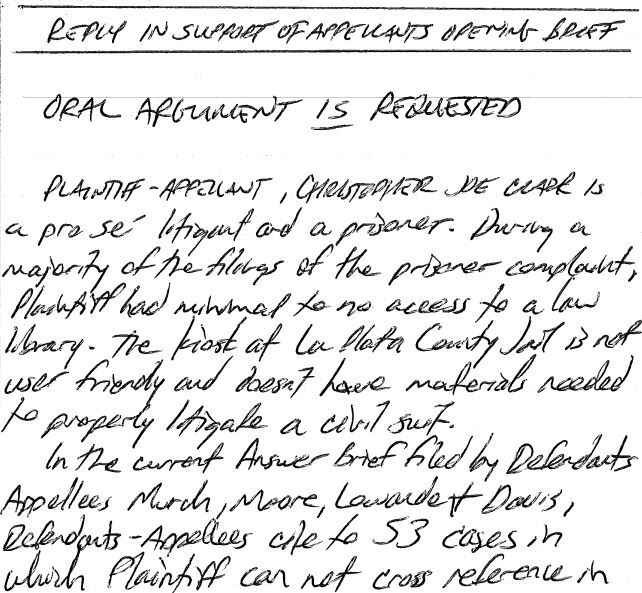

“Some of them have minimal education and have a hard time communicating on paper. The pleadings are often handwritten. It takes a long time to decipher what they are trying to say,” she told Colorado Politics.

At the same time, self-represented prisoners are occasionally able to prevail against the government and its considerable resources.

Earlier this year, U.S. District Court Judge Nina Y. Wang not only refused to dismiss two incarcerated men’s claims that the CDOC improperly denies access to sex offender treatment, but she also authorized volunteer lawyers with the Civil Pro Bono Panel to take on the case.

In 2020, the department asked a judge to end a case in its favor after an incarcerated man challenged prison officials’ decision to withhold racy images of women he ordered. U.S. District Court Senior Judge Marcia S. Krieger dealt a blow to the state, concluding the self-represented plaintiff was actually entitled to prevail because the prison violated its own policies in confiscating some of the photos.

In a reversal of the usual dynamics, she also slammed the lawyers at the Colorado Attorney General’s Office for presenting “patently-absurd” arguments – such as comparing cheerleading to a “sadistic practice” – in an attempt to prevent her from ruling in the pro se prisoner’s favor.

Homiak said that in his view, the early stages of a civil case tend to be the most critical moments when a self-represented plaintiff could benefit from legal intervention.

“These are complex, confusing procedures that involve a deep understanding of the substantive law, procedural rules, local rules and practice standards of each judge,” he said.

Mix is hopeful the court will be able to expand the program after its first year. Since the U.S. District Court enacted a rule for pilot programs less than a decade ago, all initiatives have been continued in some form. Mix estimated a couple of dozen prisoner cases from Fremont Correctional Facility are pending before the court at a given time.

“Hopefully, we’ll have enough ‘customers,’ so to speak, to make it viable,” she said. “And we’ll see how many of those result in prisoners asking good questions that we can get volunteer attorneys to take on.”