State Supreme Court interprets ‘straw purchase’ law to encompass shared use of guns

The Colorado Supreme Court on Monday interpreted a gun safety law enacted after the Columbine High School massacre, ruling for the first time that the illegal transfer of a firearm to a prohibited person can encompass the shared use of a weapon in a household.

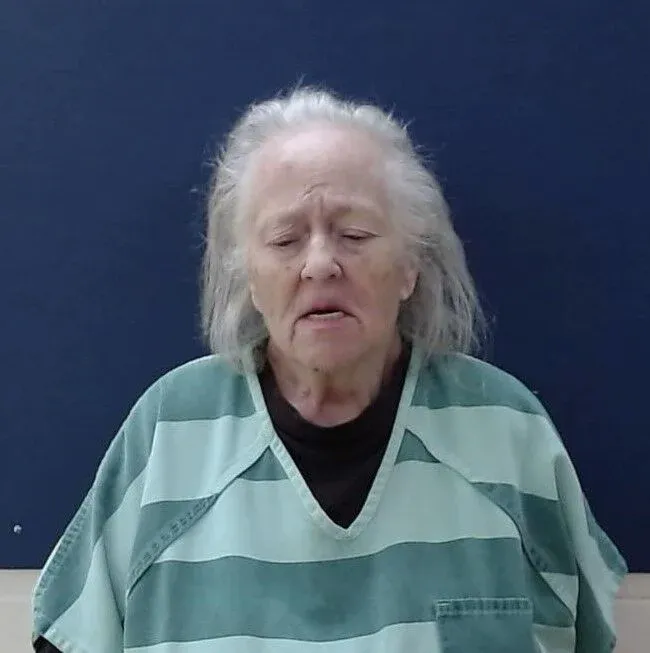

The court declined to say whether someone can violate the law on transfers by merely placing the gun in the household where a prohibited person may access it. Instead, the justices believed there was sufficient evidence to convict Sylvia Johnson of purchasing a gun in order to temporarily transfer it to her partner at home.

Following the Columbine murders in 1999, Colorado lawmakers enacted a “straw purchase” law, designed to prevent people from purchasing guns intended for use by someone else. The law makes it a felony to knowingly buy a gun “on behalf of or for transfer to a person” who is legally prohibited from owning one.

Adams County prosecutors charged Johnson under the law after the arrest of her partner, Jaron Trujillo. Officers found a gun on Trujillo, which he said belonged to Johnson. The two of them had shopped for the gun together at a pawn shop and Trujillo knew Johnson kept it in her closet. Trujillo had a prior conviction and was barred from possessing a firearm.

Johnson challenged her conviction, arguing a “transfer” to an ineligible person required more than making a gun available to the prohibited person. In 2021, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals determined the meaning of “transfer” encompassed temporary exchanges of a shared item. The panel believed the evidence supported a conclusion that Johnson bought the gun and kept it in a location where Trujillo would retrieve it.

“Johnson kept the firearm at a location where both she and Trujillo could access it; they shared possession of the firearm,” wrote Judge Lino S. Lipinsky de Orlov. “Johnson and Trujillo ‘transferred’ the firearm by conveying, moving, and shifting it between themselves. Thus, a ‘transfer’ of the firearm occurred when Trujillo picked it up from the closet, where Johnson had left it.”

The Supreme Court agreed to review the case, and held oral arguments last fall at Pine Creek High School in Colorado Springs. Johnson’s attorney, Patrick R. Henson, attempted to draw the line between actively lending someone an item and simply enabling “unsupervised access.”

“If you went to the mall and you purchased a shirt – and you know your sibling’s gonna like it – and you put it in your closet,” he argued, “did you buy that for transfer to a third party?”

“Shared possession isn’t enough? It has to be an attempt to actually hand over possession to someone else?” asked Justice Monica M. Márquez.

“I would agree with that 100%” responded Henson.

The prosecution suggested that all exchanges of firearms count as transfers.

“I buy (a gun) for the family and my 22-year-old son has access to it,” said Justice Melissa Hart hypothetically. “It’s there in the house. Did I transfer it to him?”

If someone in the household is ineligible to own a gun and the purchaser provides access, “you have problem under the statute,” replied Assistant Solicitor General Joseph G. Michaels.

The Supreme Court ultimately decided that purchasing a firearm in order to “transfer” encompasses the shared use and temporary exchange of a gun. Buying a weapon “on behalf of” a prohibited person, as the statute also outlaws, is a permanent action.

In reaching its decision, the court did not address the concern from Johnson and some of the justices that providing access to the gun in a shared household would count as an illegal transfer.

“Perhaps,” wrote Justice William W. Hood III in the Feb. 6 opinion, adding that the court could uphold Johnson’s conviction without going that far.

“Not only does the video from the pawn shop suggest a de facto joint purchase, Trujillo told the police that Johnson let him borrow the gun when he was arrested with it,” Hood wrote. Such evidence could support the jury’s verdict that Johnson knowingly purchased the gun in order for Trujillo to possess it temporarily, he concluded.

The case is Johnson v. People.