‘I was different and they didn’t want that’: Judge’s approach collides with voters’ expectations of justice | COVER STORY

In January 2021, La Plata County Court Judge Anne K. Woods presided over an emotionally-fraught sentencing hearing: Preston Edward Pitcher, a church leader, pleaded guilty to four misdemeanor offenses after sexually abusing young adults whom he groomed as children.

Despite the option to impose jail time, Woods opted against incarcerating Pitcher for 60 days and instead sentenced him to four years of probation, as the parties had agreed to.

Observers were aghast.

“What if it was your son that was molested or sexually abused?” one victim’s parent told her.

“The victims here deserve something,” the prosecutor added.

Woods, who was barely into her fourth month as a judge, attempted to make the point that Pitcher needed reformation and supervision, and putting him in a cell would not serve the community. But her actual words, as the local newspaper described the hearing, conveyed an air of insensitivity.

“I’m not going to sentence you to 60 days in jail because I just don’t see the point,” Woods said. “There’s no amount of jail that’s going to help anyone here.”

***

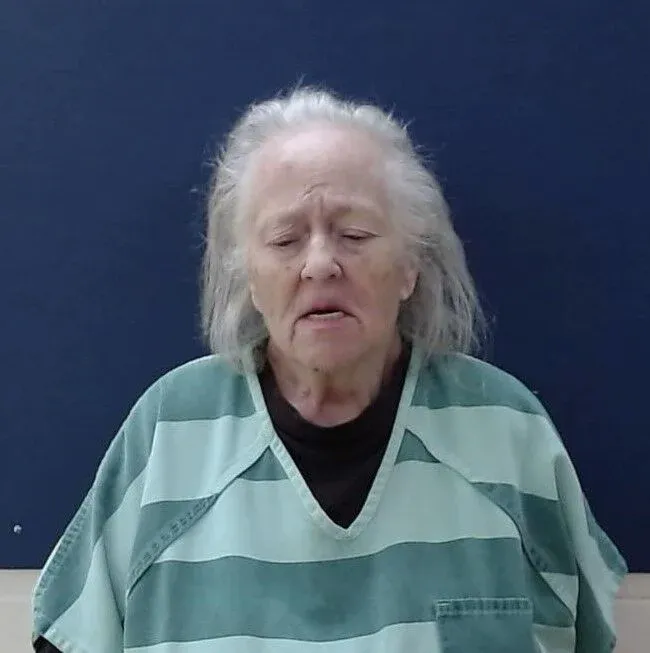

The day after the November 2022 election, Annie Woods was no longer a judge. Appointed at age 33 just two year prior, a slim majority – 51% – of La Plata County voters chose not to retain her in office.

“I had strong reactions sometimes when presiding over cases, hearing from victims who were harmed. And having the instinct to tell that defendant how horrible they were and punish them. I’m human,” she said, explaining her style as a judge. “But so are they.”

Woods was the only judge in Colorado not to be retained in 2022. It is not a rare event to have a judge come up short on a retention vote, as each of the four prior election cycles also featured judges losing their seats.

However, Woods fell into the unusual category of being non-retained despite a favorable evaluation from one of the state’s independent, citizen-led commissions that reviews the performance of judges. The performance commissions used to recommend to voters whether to retain or not retain a judge; now, they advise whether judges “meet performance standards” based on a matrix of factors.

Woods was one of several judges in 2022 to receive a split vote from her performance commission. Six members believed she met performance standards, while three did not. It was the same margin, for instance, of a county court judge in Rio Blanco County – an older man – who met performance standards despite parties in his courtroom feeling pressured to settle cases for fear the judge would get confused and misapply the law at trial. (Voters retained him by 2-to-1.)

In contrast, Woods’ commission repeatedly noted that she had improved as a judge since the time of the Pitcher hearing. And yet, its members wrote, “the Commission found the public did not see Judge Woods as fair.”

Rather than being the first signal to voters that something was wrong, the commission’s observation was actually a confirmation of the local narrative about Woods, spread for two years online and through the media.

To her opponents, Woods’ loss was a function of her approach to crime, specifically her application of “restorative justice,” which focuses on repairing the harmful effects of a crime rather than punishing the offender. In their telling, Woods’ version crossed over the line into coddling criminals.

For Woods, in contrast, the election involved a confluence of external and internal forces – of her own unfamiliarity with the job, of misinformation, of differential treatment because of her age and sex, and of a Democratic-leaning county not liking the criminal justice reform it was seeing.

“I was different and they didn’t want that,” she said.

A defense attorney with a vision

Woods graduated from the University of Denver’s law school in 2015, five years prior to her appointment. She then became a public defender in Durango, which she characterized as a “front seat” to the systemic flaws of the criminal justice system. In 2020, she applied to become the sole La Plata County Court judge, beating out two men with prosecutorial experience for the position.

Woods recalled being open with Gov. Jared Polis’ office and the citizen-led judicial nominating commission about her goals.

“I really was always a fan of procedural justice, which is the concept of giving everyone a voice, treating everyone with dignity and respect, and using plain language that people can understand, trying to be neutral,” she said. “Treating everyone the same, regardless of what they’ve said or what they’ve done.”

In Colorado, county court judges preside over misdemeanor crimes, traffic cases (including non-felony drunk driving), small claims and evictions. They also set bail for criminal defendants.

Initially, Woods struggled to adapt. Multiple attorneys told Colorado Politics that lawyers would openly demean her, and she occasionally had difficulty controlling the courtroom. An initial evaluation from her judicial performance commission in 2021 corroborated the concerns – 70% of attorneys and 100% of non-attorneys who filled out surveys believed Woods did not meet performance standards. Her lowest score was in the category of “application and knowledge of law.”

At the time, Woods felt that some of the criticism of her performance was unfair, but acknowledged she had legitimate issues to fix. In large part, there was concern the judge extended inappropriate amounts of compassion to the criminally accused.

“I just really wanted to empathize with everyone and feel like the court is a place where they are not gonna come in and the judge is gonna throw a bunch of terms at them and not help them at all,” Woods said. “I didn’t want my courtroom to be a place like that. But I definitely think I crossed the line sometimes into the category of giving advice.”

The public portrait of her was as someone who privileged the criminally accused, a reputation developed through a small number of cases highlighted in the media. There was the man for whom Woods granted bond in a DUI case, only to then drive drunk again and kill his passenger. There was a mentally-ill woman arrested for setting fire to a barn, but then led police on a high-speed chase after Woods granted her bond. And there was Pitcher’s sentencing.

Some victims corroborated the view that Woods was to blame, at least in part, for perceived leniency.

John Purser was riding his motorcycle in March 2021 when another biker hit him on a curve, injuring them both. The man pleaded guilty to a traffic offense, careless driving resulting in injury, and received a fine with no jail time. Purser, who voted against Woods’ retention, is still unhappy with her and the district attorney’s office for agreeing to the punishment.

“She didn’t require him to address me personally, to write a letter of apology, to do public service. There was virtually no consequence for what he did,” Purser said. As for the prosecution, “I’m hoping we’ll have some half-decent option when the DA comes up for election.”

Still, by 2022, the majority of Woods’ performance commission was satisfied she had improved enough.

“The public still may be partially anchored on the view that Judge Woods is a pro-defense judge,” commission members wrote to voters, “but the Commission noted a significant increase in cash bail and sentences above the minimum since the interim evaluation.”

The numbers bore out that narrative. Disapproval of her job performance dropped from the prior year. One-third of lawyers and one-quarter of non-lawyers still believed she did not meet performance standards – percentages higher than average for county court judges – but it was a steep decline from 2021.

But there was another number that foreshadowed a retention problem. In 2022, the chief judge of Woods’ judicial district, who was also up for retention, received 39 survey responses from lawyers and nonlawyers across all three counties in the district. Two other counties closest in population to La Plata – Garfield and Fremont – also had their county judges up for retention, who garnered 59 and 48 responses, respectively.

In contrast, 90 people had something to say about Woods.

Persistent coverage, persistent outrage

Marshall R. Sumrall, a private criminal defense attorney in Durango, believed Woods was doing a good job. He noticed the newspaper, The Durango Herald, published a “slew” of opinion articles, editorials and letters to the editor that were critical of Woods during her time in office.

“The Durango Herald seemed to be opposed to her from the beginning,” he recalled. “In my opinion the voters were influenced by their unfair reporting.”

Nikkolette Moyer, who worked for the court system between 2021 and 2022 and was assigned to Woods as a clerk, said the paper’s coverage bothered Woods.

“They didn’t really talk about Annie in the most positive light. All of the articles they wrote about her, there was nothing ever positive,” Moyer said. “It was just really strange how they always picked her out.”

Senior editor Trent Stephens told Colorado Politics he had “not detected a bias or known of an uncorrected inaccuracy” in The Herald’s coverage of Woods. Woods acknowledged the paper did not publish anything factually inaccurate, but argued its reporting about her sensationalized certain cases or failed to mention key facts.

For example, Woods pointed to specific articles that, in her view, laid full responsibility for a lenient sentence on her, when in reality the sentence was stipulated in a plea deal with the district attorney’s office. Another article’s sub-headline advertised that Woods “faced criticism for releasing criminal defendants on low bond amounts,” although the article itself made no mention of any criticism.

The paper was not the only venue for conversation about Woods’ approach to judging. A post on Reddit, with 89 comments, featured a discussion ostensibly about her, but veered into the merits of restorative justice and criminal procedure.

“Be honest with yourself: If you were the defendant – and we are all just a moment and a mistake away from becoming the defendant – you would want someone with compassion, integrity, and principles sitting behind that bench,” wrote one commenter.

“Repeat offenders need to be locked up, rehabilitation be damned,” responded another.

For her part, Woods avoided the Internet commentary. It was the newspaper she saw as the problem, and Woods even went so far as to mention “misinformation from small town media” in her resignation email to the chief justice the day after the election.

But then the radio ads started.

The party chair

Dave Peters is the chair of the La Plata County Republican Party. He also happens to be a member of the judicial performance commission that received information about Woods’ performance and deliberated confidentially about its recommendation to voters.

Before the election, the county party ran radio ads for 10 days, including against Woods. Peters estimated the group spent $1,000 specifically on her. The GOP also posted a voter guide that recommended Woods not be retained, with an explanation.

“Judge Woods is a far-left activist Judge, with an abysmal track record. This Polis appointee has shown time and again a blatant disregard for public safety and the rule of law,” the guide explained.

Peters denied any impropriety given his dual roles as commissioner and party chair.

“My views on the performance commission are based solely on the performance standards laid out by the state,” he said, suggesting the “much bigger” issue was the presence of lawyers on the commission reviewing the judges they appear before.

The local Democratic Party did not take a position on judicial retention.

Although the rules governing performance commissions forbid members from publicly advocating for or against the retention of judges, Kent Wagner, the director of Colorado’s Office of Judicial Performance Evaluation, said he detected no breach in this circumstance.

“I have found no indication that Mr. Peters publicly advocated against Judge Woods’ retention personally,” he said.

Gary M. Jackson, a retired Denver County Court judge and a former judicial performance commissioner in Arapahoe County, said he could not recall a prior instance of a political party advocating against a judge’s retention.

Peters’ involvement struck him as problematic, as did the party’s characterization of Woods, Jackson said.

“What was put in that voter guide, first of all, was inaccurate. That performance commission did not make a determination that her performance as a judge was ‘abysmal,'” he said. “It did not come to the conclusion that she was not abiding by the rule of law.”

And yet, at the same time Woods was narrowly losing her retention election, La Plata County voters selected Democrats across the partisan races, suggesting the county’s Republicans were far from the only demographic dissatisfied with her.

“They didn’t have enough votes to really get her out, so it had to be a lot of other people, as well. It wasn’t a one-party or one-group protest,” said Rep. Barbara McLachlan, D-Durango, who declined to say whether she voted to retain Woods.

Pulling the cards

Woods said she does not like to “pull the woman card” or the “young woman card.”

“I think it can be used as an excuse for our own shortcomings,” she explained.

But Woods nonetheless perceived differential treatment – by attorneys, by litigants and by voters – because of her age and sex. Perhaps coincidentally, of the last five judges who lost their retention elections, three were women.

“When you’re a woman or you’re a judge of color,” said Jackson, “we still live in a society and a system where we are viewed differently, and we have to work harder and longer and are not given the same leeway that white males are given.”

Public defenders, he added, have also been subject to “inherent prejudices” about their suitability for judging.

Some observers who spoke to Colorado Politics witnessed what they believed to be hostile treatment of Woods. Others, including those who worked for her and were in her courtroom frequently, did not pick up on any problematic behavior.

Woods made clear that she does not blame anyone else for her non-retention. But she also suspected those who might have labeled as “competent” a man with similar credentials instead saw her as “inexperienced.”

Ellen Stein, the former editorial page editor for The Herald and currently a corporate marketing director, voted against Woods’ retention. Stein said she is “as liberal as they come” and in favor of restorative justice. But Woods’ version of restorative justice was not what Stein wanted.

“I hate to say this – I would like to see somebody who has a little more experience under their belt,” she said. “I want to see women thrive in government and public positions, but my sense in this case is that she needs more experience.”

‘It made me grateful’

Stein’s “no” vote on Woods was driven by a specific case she handled: Preston Pitcher, the man Woods sentenced for sexual abuse, with no jail time.

“He was not sentenced to more than some kind of therapy,” Stein said. “I thought that was abhorrent.”

In reality, Pitcher’s plea agreement stipulated to four years of probation, with up to 60 days in jail as an option. Probation, in turn, includes several limitations on a defendant’s liberty, along with supervision and the possibility of incarceration for violating the conditions. In Pitcher’s case, Woods also ordered treatment.

Stein said she spoke to a lawyer she knew about Pitcher’s sentence, who agreed with Woods’ approach to rehabilitating Pitcher. But that did not convince her that what the judge did was right.

“Probation is not jail time,” she said. “I think restorative justice, when appropriately used, it absolutely has a place. But this was not a match. The scope of the crime was much greater.”

On the other side of the divide, however, was one man Woods sentenced in a criminal case, who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to be candid and also to avoid backlash from those still upset with him.

“Her kindness toward me actually helps in aiding toward no recidivism,” he said. “Because she was kind to me it actually added way more fuel to me doing right by the system moving forward.”

The man said he recognized the societal need for punishment, and the perception that a less severe sentence means he “got off.” He understood, though, that if he faltered in the treatment Woods ordered, he would be back in court again.

He voted to retain her.

“She got accused of being too light, but it wasn’t just she was letting people of the hook. I think she knew what was required of me and it wasn’t just, ‘You’re good to go’,” the man said. “It made me want to succeed.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated the gender ratio of judges recently not retained. The correct number is three out of five who were women.