Parties argue over mundane, salacious issues as DaVita trial looms

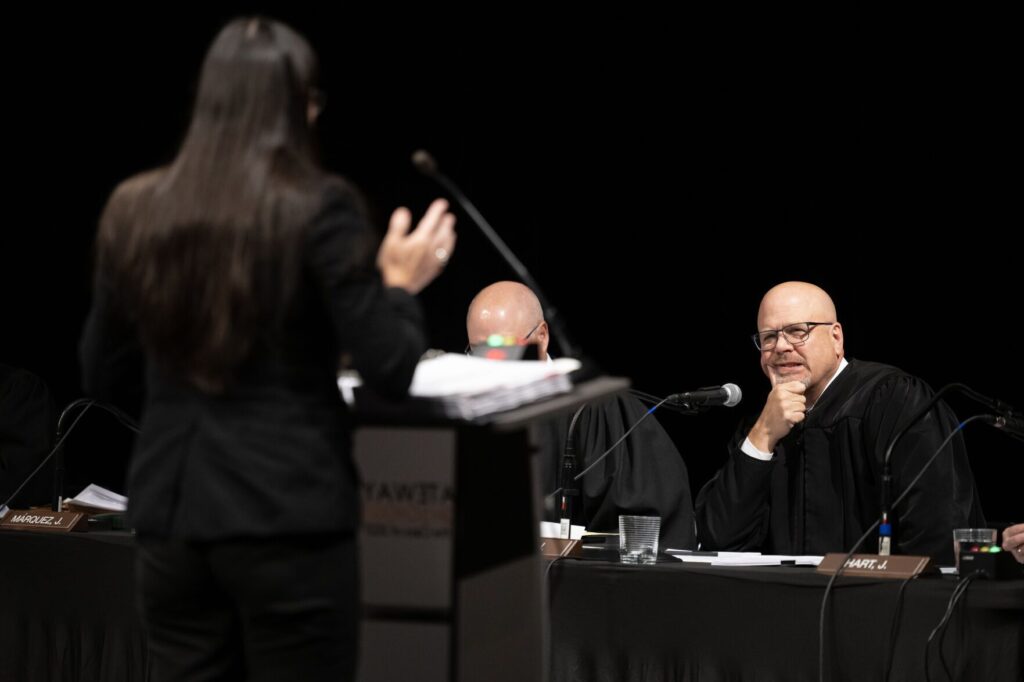

With weeks to go until the high-profile white collar trial, attorneys for the United States and for Fortune 500 company DaVita, Inc. clashed in a downtown Denver courtroom, arguing over the admissibility of expert testimony, the multimillion-dollar compensation for DaVita’s CEO-turned-defendant, and the government’s withholding of information.

The parties on Thursday even disputed whether the defense could ask a former DaVita executive and witness for the government about his marital infidelity, prompting U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson to caution against such a salacious line of questioning.

“This is really ugly,” Jackson observed.

The U.S. Department of Justice is prosecuting DaVita and its ex-leader Kent Thiry for a series of agreements with DaVita’s competitors to not solicit the company’s employees. The government believes such agreements violate the 132-year-old Sherman Antitrust Act, and will need to prove that DaVita and Thiry intended to “allocate the labor market” – meaning they restricted the movement of employees.

A three-week jury trial is scheduled to begin on March 28. Both sides and the judge have noted that this is a novel application of federal antitrust law. The parties indicated they intend to proceed as scheduled, as Jackson has little room to push back the trial date.

“The company and Mr. Thiry would like to get this matter behind them as soon as possible,” said John C. Dodds, an attorney for the defense.

The parties presented Jackson with nearly two dozen motions regarding evidence, witnesses and jury instructions. One hotly-contested matter was whether the defense’s cross examination of a government witness, Dennis Kogod, could touch on the former DaVita executive’s extramarital affair.

“We do not seek via cross examination to challenge or undermine Mr. Kogod’s credibility on marital issues alone,” said lawyer Tom Melsheimer. “We’re not doing that.”

“You’re not doing that, but now you’re gonna tell me how you’ll try to do it,” Jackson responded dryly.

Melsheimer argued that Kogod’s double-life with separate families, which was the subject of a Nevada Supreme Court decision, was “deceptive” and “fraudulent” conduct that the jury should know about in evaluating Kogod’s truthfulness.

“So now DaVita’s gonna seek to undermine their own former executive?” the judge asked.

“Well, if I have anything to say about it, yes, Your Honor, we are,” Melsheimer answered. Jackson warned the defense that such a tactic could backfire and cause the jury to sympathize with the witness.

The defense also asked to avoid mentioning Thiry’s compensation as CEO, totaling roughly $15 million in 2016, to the jury. Attorneys argued that the dollar amount could inflame the jury’s biases against Thiry. Jackson bristled in defense of the jurors.

“What are you so afraid of? You’re afraid that these jurors who will decide the fate of DaVita and Mr. Thiry are so shallow that just because he’s a rich man that made a lot of money, they’re gonna find that he’s guilty? Come on,” the judge lectured the defense.

Jackson added that he was also not sure why the government believed the jury should know Thiry’s compensation. The Justice Department responded that retaining talent in the company was a factor in Thiry’s compensation plan, and could show an incentive to enter into the non-solicitation agreements.

DaVita and Thiry stand charged with three counts of criminal conspiracy. In January, Jackson declined to dismiss the charges, and last week the government aired statements in court from DaVita’s alleged co-conspirators. Competitor companies Surgical Care Affiliates, Hazel Health and Radiology Partners were among the entities implicated in the investigation.

Emails and text messages the government presented suggested that several parties were aware of a need to avoid recruiting from DaVita. Josh Golomb, the chief executive officer of Hazel Health in California, wrote that Thiry has “my commitment we discussed that I’m going to make sure everyone on my team knows to steer clear of everyone at DaVita.”

Sara Clingan with the Justice Department reminded the courtroom on Thursday of similar statements in evidence, including “we can’t go directly into DaVita” or “we cannot recruit directly from DaVita,” and argued that the defense has yet to put forth a legitimate business reason for those directives.

The defense conceded that the trial will hinge on the intent of the parties who entered into the agreements, and whether preventing employees from leaving DaVita was the goal. Lawyers mentioned that DaVita had entered into a “strategic partnership” through the agreements, and had a practice of not recruiting from strategic partners.

That claim drew skepticism from Jackson, who noted there was nothing suggesting a strategic partnership. If DaVita was to rely on that argument to persuade the jury, the judge added, “I predict you’ll lose that case.”

Also at issue in the leadup to the trial is an expert witness for the defense, economist Pierre-Yves Cremieux, who the government does not want to testify. The defense outlined Cremieux’s data analysis, which reportedly showed that employees at DaVita did not leave the company any more or less often than in the economy generally. The expert would also offer opinions about why companies may have an economic self-interest in imposing hiring or recruiting restrictions on themselves.

The government responded that the benefits a company like DaVita would accrue from entering into non-solicitation agreements for employees were irrelevant. If prosecutors proved beyond a reasonable doubt that DaVita and Thiry intended to stifle the labor market, that was sufficient to find a criminal violation.

“If you have a conspiracy, for example, to rob a bank, the conspirators may have robbed the bank because they wanted to buy new cars,” said Megan S. Lewis. “It doesn’t mean the object of the conspiracy wasn’t to rob the bank. The reason why they did it or what they would have done with the money aren’t relevant.”

Finally, the defense asked that the government turn over notes from meetings between Justice Department lawyers and the attorneys for potential witnesses. Jackson described the meetings as negotiations, without the witness present, outlining what the witness would be willing to testify about.

Lewis labeled the request a “sideshow” because the notes did not amount to evidence and the government had already turned over witnesses’ actual statements to the defense. Jackson pressed Lewis on her recalcitrance, and indicated that her reasons for refusing to hand over the notes were insufficient.

“If it’s just duplicative of what you’ve already shown, why should they take your word for it?” the judge demanded. “You’re trying to put Mr. Thiry in jail. Why should he believe you?”

The case is United States v. DaVita Inc. et al.