Federal judge cites no power to review Colorado Supreme Court decision, rejects discipline lawsuit

Citing the longstanding prohibition on federal judges reviewing decisions of state courts, a magistrate judge has tossed a lawsuit from a paralegal who sought to overturn the Colorado Supreme Court’s 2019 sanction of her.

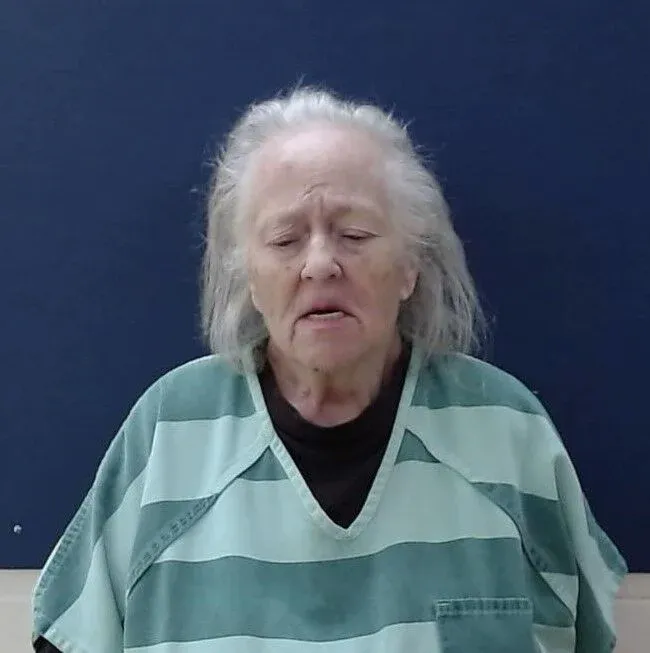

Susan Renee Zebelman Vigoda of Boulder sued the state’s Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel, among others, for its investigation of her following allegations that Vigoda was practicing law without a license. The proceedings initiated by OARC culminated in a January 2019 order from the state Supreme Court holding Vigoda responsible for $1,724 in fines, restitution and other costs.

Although Vigoda sought to overturn or expunge the disciplinary decision and to have the Supreme Court “cease doxing” her by removing her name from its website, U.S. Magistrate Judge Scott T. Varholak concluded the federal trial courts were no place for Vigoda to litigate the issue.

Because of the Rooker-Feldman doctrine, which the U.S. Supreme Court first articulated in 1923, “only the United States Supreme Court has appellate authority to review a state-court decision,” Varholak wrote on Feb. 11.

According to a report from Colorado’s presiding disciplinary judge, Vigoda entered into an agreement in 2016 to assist Janet Rosendahl-Sweeney and her then-husband with setting up a trust for their sons. The agreement stipulated that Vigoda would not provide legal advice and that her services would amount to administrative assistance.

Soon after, Rosendahl-Sweeney and her husband filed for divorce. Vigoda assisted the couple in the early stages, and then Rosendahl-Sweeney paid Vigoda $1,000 for helping prepare and file court documents. According to Rosendahl-Sweeney, Vigoda said she had the “legal expertise” to get Rosendahl-Sweeney “everything she wanted” in the divorce.

Vigoda’s assistance subsequently encompassed more than administrative matters. She reportedly drafted motions and advised Rosendahl-Sweeney to avoid mediation. Rosendahl-Sweeney eventually ended her relationship with Vigoda after the state court repeatedly sided with Rosendahl-Sweeney’s husband.

Presiding Disciplinary Judge William R. Lucero, who was a defendant in Vigoda’s federal lawsuit alongside Rosendahl-Sweeney and OARC, concluded Vigoda had engaged in the unauthorized practice of law.

“Even though Respondent informed the Sweeneys that she was not a lawyer, Rosendahl-Sweeney relied and acted upon Respondent’s legal advice by filing documents and pleadings in her divorce that Respondent had drafted,” Lucero wrote on Nov. 6, 2018. “Respondent’s actions caused Rosendahl-Sweeney harm, including lost funds that she paid Respondent for those services and the receipt of poor advice resulting in adverse Court rulings in the divorce.”

Although Lucero documented Vigoda’s repeated protestations about her health and disability during the proceedings, he also harbored doubts about what he heard – including his belief that someone claiming to be Vigoda’s in-home aide was Vigoda herself. The Supreme Court upheld the financial penalty Lucero recommended, and barred Vigoda from practicing law without authorization.

In her lawsuit, Vigoda labeled the proceedings as “unjust legal persecution” that harmed her reputation. She alleged that because her caretaker could not assist with her defense and OARC did not provide accommodations for her disability, her legal rights were violated.

“Renee submits that her treatment in the case was demeaning, as she was threatened and persecuted without the acknowledgement of and accommodations for her disabilities,” wrote Vigoda, who represented herself.

In pursuing her case against the government actors, Vigoda also leveled allegations that Rosendahl-Sweeney falsely held herself out as a medical practitioner and deliberately harmed her own son, prompting Rosendahl-Sweeney to file counterclaims against Vigoda for perjury and libel.

By December 2021, things had deteriorated to the point that Rosendahl-Sweeney, also representing herself, asked the federal magistrate judge for a no-contact order. She presented a statement from Vigoda’s purported assistant describing Vigoda’s “unhealthy and vindictive obsession with Janet Sweeney.”

Varholak called the allegations “concerning,” but noted that state courts would be better-suited to handle requests for a protection order.

Pursuant to the Rooker-Feldman doctrine barring lower-court review, Varholak dismissed all of Vigoda’s claims against the government defendants, finding he had no jurisdiction to hear those. In doing so, he referenced a case decided in August in which the federal appeals court for Colorado affirmed it could not hear an attorney discipline lawsuit filed against Lucero and the members of the state Supreme Court, owing to the Rooker-Feldman principle.

Varholak also tossed the remaining claims from Vigoda and Rosendahl-Sweeney against each other, given that they were based entirely on state law.

Rosendahl-Sweeney told Colorado Politics that she continues to view Vigoda as a danger to her, and as someone who refuses to take responsibility for her actions.

“I think it was just that the case was dismissed because it was based on lies,” she said.

Vigoda reiterated after the decision that she had not committed the offenses the presiding disciplinary judge found she committed.

“I cannot speak at this time, and am looking forward to recovering (medically) in order to clear up matters,” she said.

The case is Vigoda v. Rosendahl-Sweeney et al.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with comments from Vigoda.