Justices critical of continuous home video surveillance without police warrant

Colorado’s Supreme Court justices expressed concern with allowing police to initiate continuous, long-term surveillance of a home, including its driveway and backyard, by installing a camera mounted to a utility pole.

At oral arguments on Tuesday, all seven members of the Court pushed back at various points against the state’s position that warrantless visual surveillance did not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches.

“There would be no problem from your perspective in the police deploying video cameras on every utility pole in every residential neighborhood in the state. Is that right?” asked Justice William W. Hood III.

Senior Assistant Attorney General Rebecca Adams replied in the affirmative. “I don’t think from a constitutional standpoint that would be a problem,” she said.

At issue was a pair of cases from Colorado Springs, in which police mounted a camera onto a telephone pole outside a suspected “stash house” where drug deals took place. The camera could zoom, pan and tilt, and peered over the property’s 6-foot privacy fence. It recorded continuously between May and August 2015, and law enforcement used the footage to observe and make arrests for drug transactions.

The government’s argument for the constitutionality of this surveillance technique asserted the defendants, Rafael Phillip Tafoya and Gabriel Sanchez, had no reasonable expectation of privacy by meeting on Tafoya’s property. From the street, a person could see Tafoya’s driveway and front yard. In addition, someone who had climbed the utility pole or been inside a neighboring two-story apartment complex could have peered into the backyard. Those were the areas in which the police saw the two men exchange drugs, according to court records.

“Because Tafoya’s backyard was exposed to the public, Sanchez had no expectation of privacy that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable,” Adams wrote to the Court in her brief.

In unusually personal terms, Justice Melissa Hart engaged with Adams over how far the state believed its right to spy on persons occupying their own property extended.

“The utility pole that’s in my backyard — if someone were to put a pole cam up there, they’d be able to see into my backyard completely, despite my having just built a new fence,” Hart explained. “They’d also be able to see into my 18-year-old daughter’s bedroom windows if she didn’t keep her shades pulled down all the time.”

She asked Adams whether the government would consider that circumstance problematic. Adams conceded it was a valid concern.

“So without a warrant, the police could put a pole camera up that would look into my daughter’s windows such that even if she kept her shades closed a lot of the time, anytime she didn’t,” Hart pressed, “people would be able to watch her and the police would have access to her private life because she didn’t shut her shades?”

She voiced her belief that the scenario she outlined constituted a reasonable expectation of privacy, and that “most people you ask would actually be quite surprised that the police could be videotaping your backyard all the time. That anything there, no matter what … would be subject to police surveillance.”

Police first installed the camera after receiving a tip about drug activity in the 700 block of Bennett Avenue. According to police reports, the video footage on two separate occasions caught Sanchez driving onto Tafoya’s property and the two men moving bags between the vehicle and the garage. Later, three other men arrived in a separate vehicle. They removed the spare tire and rolled it into the backyard, out of view, and subsequently reattached it.

In both instances, law enforcement pulled over the second vehicle. The first time, they found $100,000 in cash in the spare tire. The second time, they confiscated three white bags with methamphetamine and cocaine. A subsequent search warrant of Tafoya’s garage resulted in the discovery of additional drugs, and police also found cash in a secret compartment of Sanchez’s vehicle.

Juries convicted both men of possession with intent to manufacture or distribute a controlled substance. Tafoya received 15 years in prison and Sanchez received 20.

The trial court denied the defendants’ motion to suppress evidence, after Tafoya and Sanchez argued the surveillance violated the Fourth Amendment. However, in November 2019, a three-member panel of the Colorado Court of Appeals ruled the use of the camera to be an unconstitutional search. Although the panel recognized no reasonable expectation of privacy existed for areas of a home that the public could view, the decision hinged on a key point: no member of the public would stand on the utility pole or any other public vantage point for three months to conduct surveillance.

“Crediting the People’s argument would mean there is no temporal cap on how many months or years the police could have continued the video surveillance of Tafoya’s property,” wrote Judge John Daniel Dailey in the court’s opinion.

The state warned that the appellate panel’s ruling “limits the ability of law enforcement to investigate unlawful activity,” but the justices’ line of questioning indicated such an outcome was not where their concern lay.

“Isn’t it just the pervasive, 24/7 — for months and months — that is not really what you would expect? And is that unreasonable?” wondered Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright.

“If they’re gonna do this lengthy surveillance, why not get a warrant?” added Justice Richard L. Gabriel.

Both sides pointed to court cases arising from elsewhere in the country to reinforce their positions. The state cited a 1986 decision from the U.S. Supreme Court holding that the airplane surveillance of a marijuana grow operation in California was constitutional. The owner’s expectation of privacy “from all observations of his backyard” was unreasonable, a majority found.

And in 1967, a majority of the Supreme Court established that “[w]hat a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection.”

However, the defense presented a 2020 decision from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, in which police similarly installed pole-mounted cameras to monitor a drug distribution network. The Court concluded the warrantless surveillance was a “search,” for which the government needed to show probable cause.

In the Colorado Springs case, defense attorneys likened the practice of long-term home surveillance to a “big brother” activity.

“The pole cameras here allowed investigators to overcome several practical challenges to pervasive human surveillance, be that of the nosey neighbor or the common policeman,” the defense argued in their court briefs. “All of the footage collected by the cameras was stored digitally, in a searchable format, such that investigators later could comb through it at will. The pole cameras thereby gave investigators the ability to pick out and identify individual, sensitive moments that would otherwise be lost to the natural passage of time.”

The ACLU of Colorado, which supported Tafoya and Sanchez, also argued the court’s blessing of the police’s conduct in Colorado Springs would lead to a slippery slope of pervasive warrantless surveillance.

“Without any regulation under the Fourth Amendment or the state constitution, officers could unceasingly watch the comings and goings of the local political gadfly, track who leaves home with a protest sign on the day of a Black Lives Matter demonstration, or observe in detail every socially distanced front-yard interaction between neighbors or friends,” the civil liberties group wrote to the court.

The defense also questioned whether satisfying the legal expectation of privacy would require “an enclosure consisting of an impermeable barrier in three dimensions” around a home. In light of drones and satellite imagery, which make long-term surveillance cheaper and easier, some of the justices acknowledged an evolving privacy standard.

“Why isn’t the aggregation and the recording and the long-term nature of this, why does that not, in fact, change the expectation of privacy?” Justice Monica M. Márquez wondered.

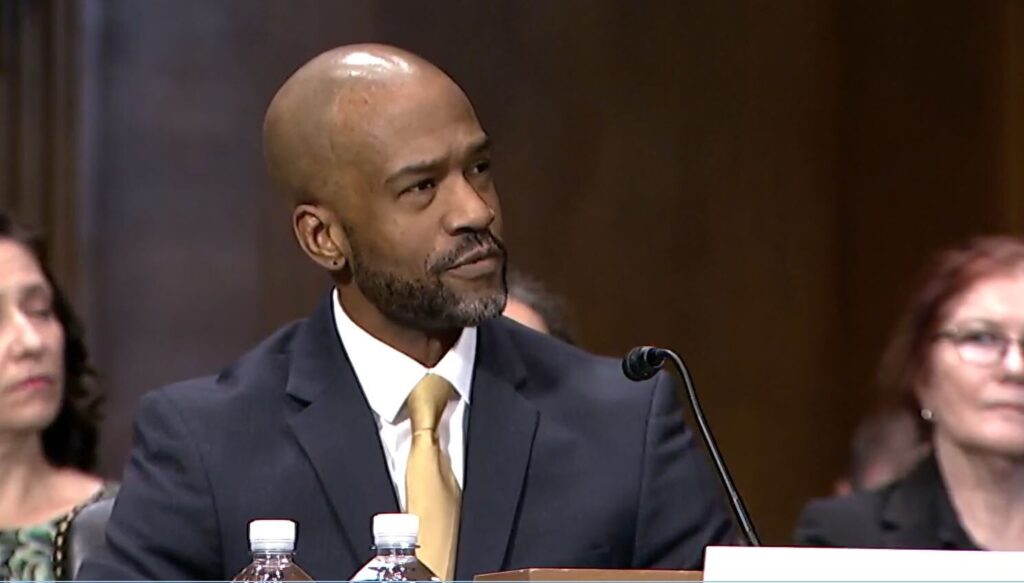

Robert Borquez, the attorney for Tafoya, told the Court that it was the combination of video technology, the length of time on camera and the continuity of the surveillance that created a problem. Nathan Wessler, representing the ACLU, did not advise a specific length of time after which warrantless surveillance should be deemed “long term,” but advised that any time limitation is better than no limitation.

The cases are People v. Tafoya and People v. Sanchez.