Specter of bribery central to argument in ‘faithless elector’ case

In a pair of “faithless elector” cases from Colorado and Washington on Wednesday morning, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed whether it would cause chaos if states could not bind their Electoral College members to the winner of their popular vote – and if they could do so, what other limits states may impose on electors.

“There must be times when electors and only electors are best placed to act in the interests of the country,” argued Jason Harrow, the attorney for Democratic Colorado elector Micheal Baca. Baca was removed from his role in the 2016 presidential election when he attempted to vote for someone other than Hillary Clinton, who won the popular vote statewide. State law binds Electoral College members to the popular vote winner.

Harrow felt that states had narrow authority to regulate presidential electors, explaining that “there are no limits in that voting by ballot, so long as the vote is for a person.”

That prompted Chief Justice John G. Roberts to interrupt, “Not a giraffe? Of course they have to vote for a person!” He observed that Harrow’s position on the autonomy of electors “sounds pretty limitless to me.”

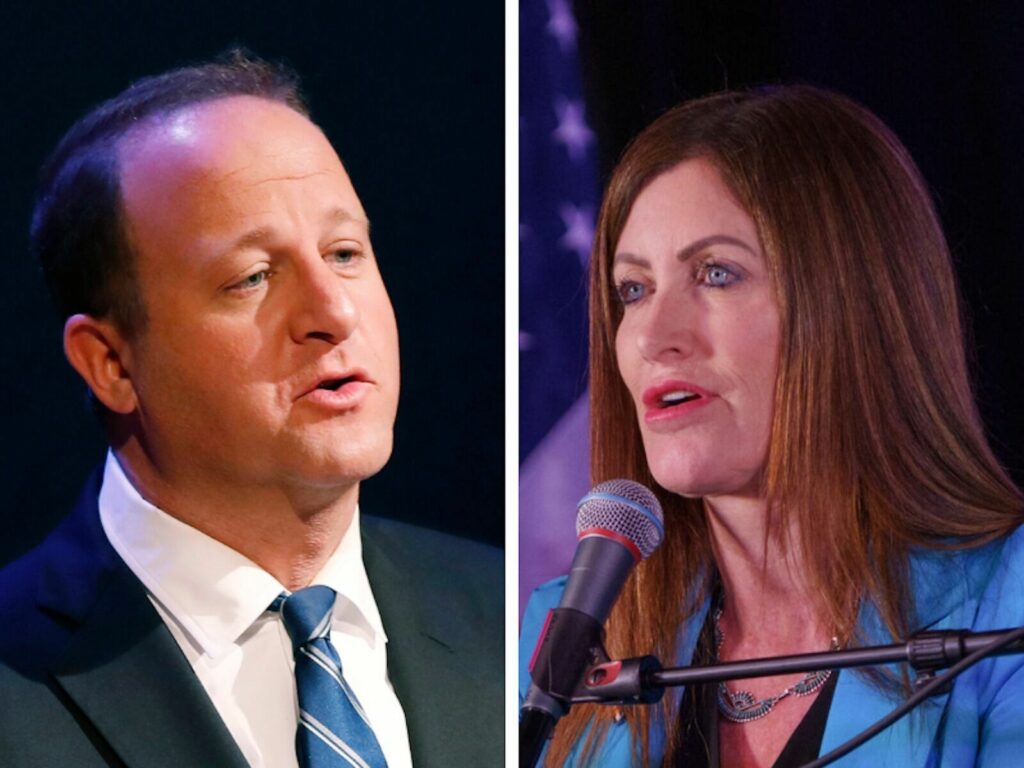

Attorney General Phil Weiser presented on behalf of the Colorado Department of State, saying that as long as states do not violate other constitutional provisions, they are free to impose other restrictions. That prompted justices to ask whether state legislatures could require their electors to only vote for a candidate who espoused certain policy positions or, as Justice Neil Gorsuch wondered, only for a candidate who visited the state.

“I don’t see off the top of my head any other constitutional constraint that would address that issue,” Weiser responded to Gorsuch.

The attorney general repeatedly referenced the specter of electors who are bribed, characterizing the defendants’ position as not allowing removal even in that instance. That would “occasion a constitutional crisis,” he said. Justice Stephen G. Breyer countered that there had never been a case of proven bribery in the Electoral College’s history.

Harrow, on the other hand, claimed that it was Colorado’s binding law that could cause problems should electors be called upon to address an extraordinary result in an election.

“If Colorado is permitted to undo the human check baked into the system of presidential selection, there could be a chaotic outcome,” he said.

The case of Colorado Department of State v. Baca came to the Supreme Court after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit ruled in favor of Baca. Forty-four states and the District of Columbia filed a brief in support of states’ ability to bind their electors. They asked the court to review the decision in order to establish clear guidance for the 2020 presidential election.

As part of Colorado’s argument, Weiser alleged that Baca did not have standing to sue because removal from a volunteer or honorary position without a salary did not amount to a personal injury. Harrow countered that his client received $5 for his duties as an elector, per Colorado statute.

Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. pointedly asked Harrow to address the fear that unbinding electors would unleash post-election campaigns to sway their votes and alter the outcome.

“Do you really deny that this is where your argument would lead?” Alito asked.

“We do deny it,” Harrow responded.

Immediately prior to the Baca case, the court heard arguments in a related matter arising from Washington. In that case, Chiafalo v. Washington, there was a challenge to that state’s law which levyied a fine for electors who did not cast a ballot for the candidate of their party. Washington subsequently replaced that statute with a law mirroring Colorado’s removal procedure.

The lawyer for the Washington electors, Lawrence Lessig, said that the 12th Amendment to the Constitution did not envision for states to be “proctors,” looking over the shoulders of electors.

“You don’t need to police the vote to be able to police corruption,” he explained in response to the concerns about potential bribery. Referencing a 1952 Supreme Court case that found it permissible for political parties to require electors sign a pledge to vote for a candidate, Lessig agreed with that conclusion, but found the legal enforcement of such a pledge problematic.

Washington Solicitor General Noah Purcell disagreed with Lessig’s reading of the Constitution and the founding period.

Allowing electors to govern themselves “leads to the absurd consequence that everything we think of as the presidential election process currently is largely advisory,” he said. “States have authority to set valid conditions,” such as the requirement to attend the meeting of the electors or being a state resident. “If the condition is valid, the condition can be enforced,” Purcell added.

Lessig in his brief compared electors to members of a jury who are entitled to use their discretion. Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that this was not a perfect comparison. If a juror commits misconduct, a judge may remove them, she said. So why should the same principle not apply to electors?

“The elector has immunity in his or her vote,” Lessig replied, clarifying that electors could not commit crimes wantonly without repercussions from the state.

Sotomayor recused herself from the Baca case, citing her friendship with one of the co-litigants, Polly Baca. After the oral argument, Weiser said that her absence could be a “bummer for us” if the court ruled 4-4 and allowed the 10th Circuit’s decision to stand. However, he explained that if there were a 5-4 decision in the Washington case, that would have the same effect as a majority ruling in the Colorado matter.

Commenting on the format of the argument, which, in a longstanding break from operating procedure, occurred by teleconference, Weiser added that “not seeing the body language is a huge challenge….I’ve been told that you seem faster when you’re over the phone as opposed to in person. So how to pace yourself is a challenge.”

Find a recording and transcript of the arguments, as well as the docket for the case, at the Supreme Court’s website.