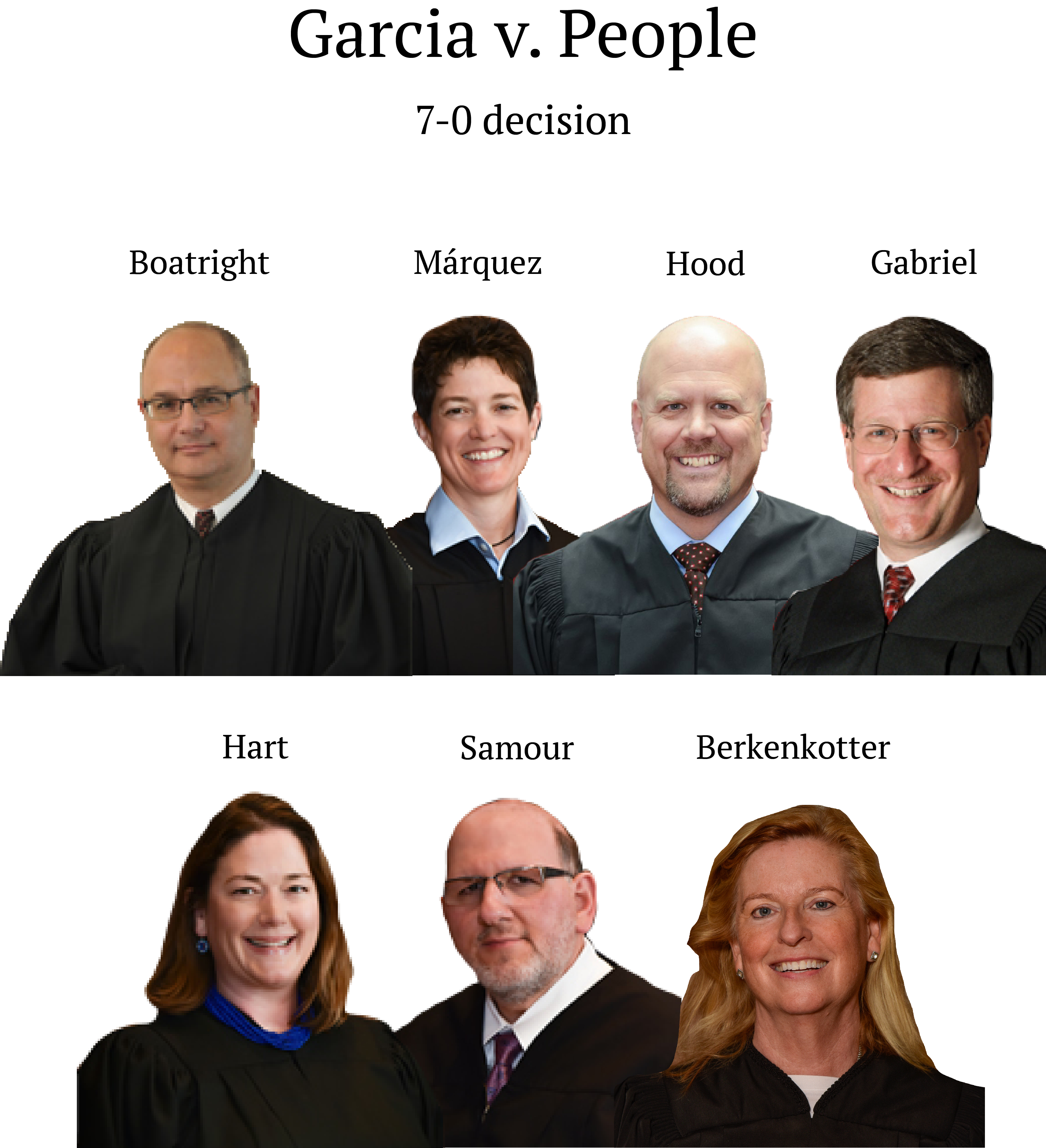

Colorado Supreme Court says Mexican acquittal did not bar man’s Mesa County murder prosecution

Even though Mexico’s judicial system acquitted a man for a murder he committed in Mesa County, there was no prohibition against Colorado prosecutors also charging him for the offense when he returned, the state Supreme Court ruled on Tuesday.

A jury found Rafael Aguilar Garcia guilty of murder in 2017, nearly three decades after he killed Charles Porter in Palisade and five years after Mexican authorities acquitted him of the crime. Garcia initially fled to Mexico after the murder but returned to Colorado under the impression that the constitutional prohibition on double jeopardy would preclude a second prosecution in the United States.

He was wrong.

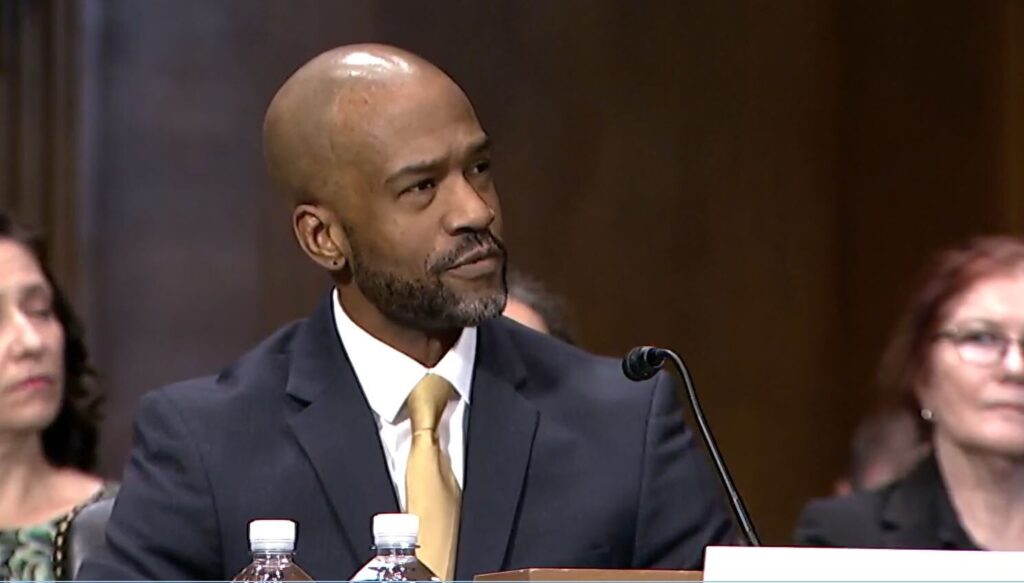

“We reject these claims and conclude that, under both the United States Constitution and state law, Mesa County was entitled to prosecute Garcia despite his earlier prosecution and acquittal in Mexico,” wrote Justice Melissa Hart in the June 20 opinion.

Double jeopardy prohibits the government from prosecuting someone twice for the same offense. There is an exception, however, under the “dual sovereignty doctrine” – the idea that a person’s conduct can violate the laws of both federal and state governments, for example, and can be prosecuted under each.

Colorado has curtailed the dual sovereignty doctrine with a law that bars successive prosecutions involving other states, the federal government or municipalities. The Supreme Court has also acknowledged tribal governments fall into that category.

Garcia argued the law should be read to also encompass the Mexican state where he was originally prosecuted. The justices were unconvinced, reasoning the legislature purposefully omitted foreign states and countries from the list.

“And, while Mexico is made up of states, many other foreign countries are not – for example, Canada is made up of provinces, and France of regions and departments,” Hart wrote.

Garcia also contended his first prosecution was a “sham” that Colorado authorities were actually controlling. Because Mexico would not extradite Garcia given the potential death penalty he would face for murder at the time, state prosecutors sent a “casebook” with evidence to Mexico so that Mexican authorities could prosecute him under Article IV of its federal penal code. Article IV applies to Mexican citizens in Mexico who have committed a crime in another country.

Garcia argued to the Supreme Court that the Mexican case against him was essentially a front for Colorado prosecutors given the level of assistance provided. Again, the Supreme Court disagreed.

“Routine intergovernmental assistance between sovereigns, without more, does not rise to the level required,” Hart wrote. “No Colorado or United States authorities were involved in the courtroom proceedings. No Colorado or United States law was applied. Garcia was tried under Mexican law and acquitted in a Mexican court, and his acquittal was affirmed by a Mexican appellate court.”

Last year, a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, in a case that originated in Colorado, affirmed that an American Indian man was properly prosecuted in tribal court and then in federal court for the same conduct under the dual sovereignty doctrine. The dissenting justices questioned the validity of the theory, with Justice Neil M. Gorsuch warning that a prosecution in one jurisdiction can serve as a “dress rehearsal” for a prosecution in another.

The case is Garcia v. People.