Appeals court says COVID-19 trial precautions were constitutional

Colorado’s second-highest court ruled for the first time on Thursday that pandemic-era health precautions during jury trials, specifically masking and distancing for jurors, did not violate a defendant’s constitutional rights.

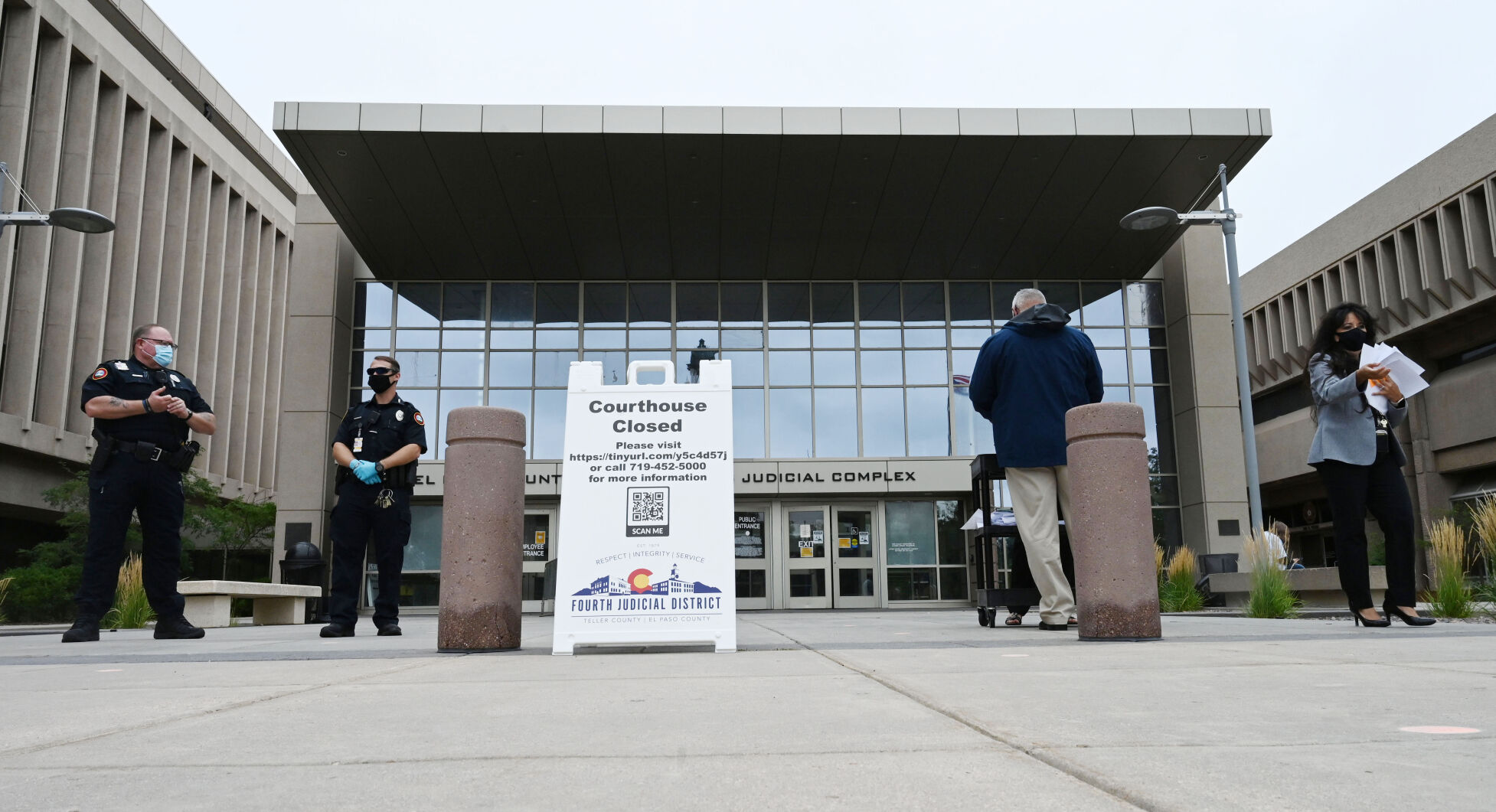

Kenneth L. Garcia’s jury trial in July 2020 was the first to take place in Denver after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, the judicial branch instituted safeguards to avoid infections, based on public health orders in place at the time.

Following his conviction, Garcia challenged the masking and distancing of participants in the courtroom, alleging the practice violated his constitutional rights to due process, to confront the witnesses against him, and to have a fair and impartial jury. Garcia even blamed the state for not planning constitutionally-compliant protocols based on the last similar crisis – the influenza pandemic of 1918.

But a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals rejected Garcia’s assertions in their entirety.

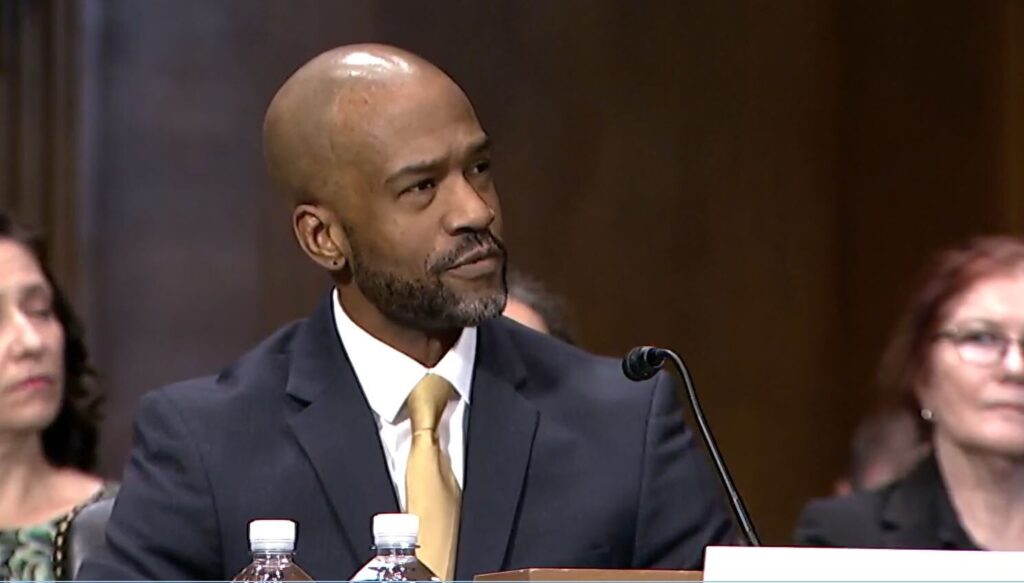

“We join the several courts from other jurisdictions that have considered this question and have concluded that such precautions in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic do not violate a defendant’s constitutional rights,” wrote Judge Anthony J. Navarro in the panel’s Dec. 22 opinion.

Prosecutors charged Garcia with multiple offenses based on allegations he robbed the 78-year-old woman who hired him for repair work. A jury found him guilty and he received a nine-year prison sentence.

Although the judicial branch was under an order from the chief justice suspending jury trials, Garcia’s case was the first in Denver allowed to proceed as a pilot. The plan entailed having jurors sit in the public gallery and remain six feet apart, to require mask-wearing, to turn the defense and prosecution tables to enable jurors to see the parties, and to permit witnesses to wear face shields while testifying.

Ahead of trial, the defense filed objections to the procedures. Garcia claimed mask-wearing would inhibit the attorneys from analyzing the suitability of potential jurors, and would make it difficult for jurors to assess the credibility of witnesses or the defendant. Further, some jurors would not be able to see Garcia clearly under the seating arrangement.

“The court believes that it has taken all the appropriate precautions, and if there’s anything further that we can help with, we will – we’ll provide those,” responded District Court Judge Shelley I. Gilman.

On appeal, Garcia raised several of the same concerns. Specifically, he argued it was difficult for the defense to determine whether to dismiss a given member of the jury pool during selection because the lawyers could not accurately gauge facial expressions.

“Because of the procedures, it is impossible for the defense to know whether a juror should have been challenged for cause based on a hidden facial response to questioning or another juror’s responses,” wrote defense attorney Lucy H. Deakins.

Deakins also pointed out the seating arrangement, in which some jurors sat eight feet farther from the defendant than normal, meant they could not assess the demeanor of Garcia or of witnesses as easily. She cited the 1918 flu pandemic as evidence that COVID-19 “should also not have been a surprise,” and the judicial branch should have been better prepared to accommodate defendants’ rights.

The government responded that no legal authority dictated people’s entire faces must be visible in order to comply with the Constitution.

“Defendant had a right to ask the prospective jurors questions – not a right to observe their noses and mouths,” wrote Assistant Attorney General Brian M. Lanni. He added there was overwhelming evidence of Garcia’s guilt, and this was not a case that depended on the credibility of witnesses.

The Court of Appeals panel looked to several other court rulings throughout the country that evaluated similar claims about COVID-19 protocols. It found little support for Garcia’s allegations.

Although the Colorado Supreme Court has acknowledged a juror’s demeanor and body language are important, “a mask covering a juror’s nose and mouth does not make it impossible to assess the juror’s demeanor,” Navarro explained.

“Moreover, even if the prospective jurors’ masks made assessing their demeanor marginally more difficult, both the defense and the prosecution were equally burdened by this challenge,” he continued.

As for Garcia’s seating chart concerns, the panel interpreted the issue as implicating Garcia’s right to confront the witnesses against him. But the appellate judges found no constitutional violation, as the witnesses did not wear masks while they were testifying and Garcia had not alleged jurors were incapable of hearing anyone speak.

The panel called it “debatable” whether a defendant has the right for jurors to observe him throughout trial, but in any event, the seating arrangement furthered an important public policy – “ensuring the safety of everyone in the courtroom in the midst of an extraordinary global pandemic by having jurors sit apart,” Navarro concluded.

The case is People v. Garcia.