‘I’m not proud of this’: Jurors in DaVita hear from witnesses who carried out allegedly illegal agreements

Jurors on Tuesday learned details about the alleged conspiracy to keep workers locked in their jobs by DaVita, Inc. and its former leader Kent Thiry, hearing directly from two people who enforced the terms of the agreements or understood the motivations behind them.

A key government witness, Bridget “Bridie” Fanning, recalled how uncomfortable she felt as a human resources professional being asked to ignore the entreaties of DaVita workers seeking to leave their jobs, but, unbeknownst to them, were seemingly barred by an agreement Thiry engineered with the CEOs of other companies.

“I was uncomfortable with it. I never liked it,” testified Fanning, who holds multiple advanced degrees in management and has been involved in the hiring of thousands of people over her career. The agreement with Thiry threw up roadblocks to recruiting DaVita employees “even when they really wanted to be considered by the company for an opportunity there. It was hard to tell the individual, ‘No you can’t be because of an agreement.’ No, I never felt comfortable about it.”

A former DaVita executive who once considered himself one of Thiry’s right-hand men also asserted to jurors that Thiry was personally bothered by the notion that other companies, led by former DaVita workers, would dare to lure away his people in an act of perceived disloyalty.

“Mr. Thiry took a lot of pride in the executives he hired and the idea of someone poaching them set off an emotional response – anger, discussion of retaliation,” said Dennis Kogod, a former chief operating officer for DaVita.

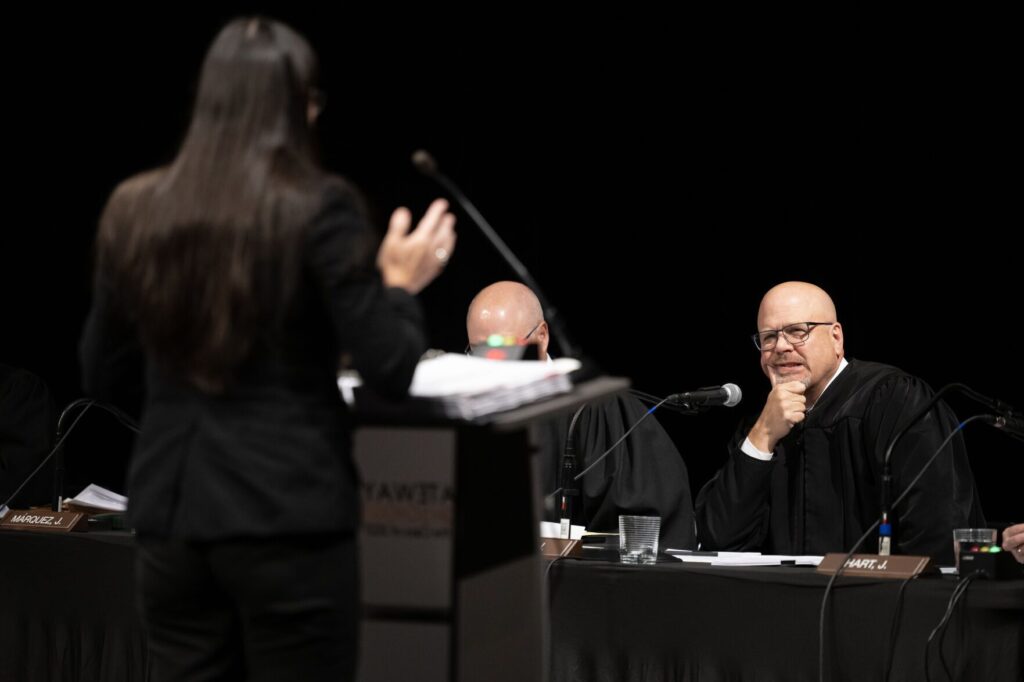

It was the first day of witness testimony in the criminal trial of kidney dialysis company DaVita and its politically-involved former CEO, Thiry. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division has charged the company and Thiry with three counts each of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, a federal law broadly intended to crack down on monopolistic or anticompetitive behavior, like price fixing or bid rigging.

In a novel interpretation of the 132-year-old law, the government alleges the defendants intended to “allocate the market” – or restrict the movement of workers between companies that competed for the same talent pool – through a series of agreements not to solicit DaVita’s workers with three specific companies.

Outside the presence of the jury, the government raised an issue stemming from the defense’s opening statement on the first day. Attorney John C. Dodds had told jurors that there were more than 400 companies from which Surgical Care Affiliates, one of the parties to the non-solicitation agreements, could look to for workers. The government on Tuesday worried that jurors may have received the impression from those numbers that DaVita could not illegally restrict the market by only having agreements with just three, as opposed to all, companies in the labor market.

U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson balked at the idea of issuing an immediate clarifying instruction, but raised the issue again at the end of the day to acknowledge he likely agreed with the government.

“I have a very strong desire to help this jury steer through your disputes and reach a decision,” Jackson said. “But in the process, (Dodds) told this jury something that in my view isn’t right. And they’re over there, I think potentially thinking, ‘How can there be an allocation of the market when there are hundreds of companies these people can go to. They got shut out of one? OK, too bad for them’.

“That isn’t what the law is,” Jackson added.

Fanning’s testimony illuminated how the non-solicitation conspiracy affected DaVita workers in practice. Fanning was an independent contractor who oversaw hiring for Surgical Care Affiliates, a company led at the time by former DaVita executive Andrew Hayek. Hayek had agreed with Thiry not to recruit each other’s senior-level employees, but the non-solicitation agreement contained an unusual provision: To be considered for a position, an employee at DaVita had to first tell their company they were seeking other employment at SCA, and vice versa.

“I had never seen that before. It was the first time in my career I had seen that,” Fanning remembered. She added that DaVita was a “talent-rich organization” and it was highly unusual to have a company-wide “hands-off” agreement that had no expiration date.

Jurors heard about the importance of corporate recruiting firms being able to solicit already-employed workers for opportunities elsewhere. Around 80% to 90% of high-level jobs, Fanning said, are filled through recruitment or by referrals. Even if a recruitment does not result in a job offer, an employee may realize through the process how high the market is compensating their skillset. It may be possible to use that knowledge to obtain a raise without needing to change jobs.

She added that non-solicitation agreements are beneficial to employers because they avoid disruption to businesses by keeping workers in their jobs. They are simultaneously harmful to employees, she said. In one instance, a DaVita worker unaware of the agreement repeatedly pitched himself as a job candidate, but Hayek nixed the possibility of hiring him.

Instead, Fanning had to tell the DaVita employee that SCA had a “priority strategic partnership” with his company that precluded the man’s hiring.

“I’m not proud of this email,” she said after reading it aloud to the courtroom. “I’m dressing it up to make it more official and formal than it actually was.”

Fanning had to repeatedly remind recruiters that, due to the agreement with Thiry, they could not contact DaVita employees.

“Nope completely off limits unless they have left – or talk to their boss and get permission,” Fanning emailed to a recruiter who was confused about the limitation on DaVita.

Kogod, the former chief operating officer, testified that Thiry would seek to “target” or “retaliate” against CEOs he felt were disloyal – people who, like Hayek, were former DaVita higher-ups who sought to hire away talent once they reached the top of their own corporate ladder. DaVita executives were expected to “elevate” reports of their employees being under consideration for jobs elsewhere.

“They didn’t want to be the executive who had an employee recruited by one of these companies and didn’t raise it to the senior team,” he recalled.

Kogod also described the broader ethos of DaVita: Known as “the village,” the idea was that DaVita, with personnel spread over the country and the world, was more than just a workplace. Thiry sometimes was known as the “mayor” of the village.

However, “it felt like over time ‘the village’ became less about the DaVita ‘village’ and more about Kent,” Kogod said. He pointed in particular to the stipulation in the non-solicitation agreements that current DaVita employees tell their bosses of their intent to leave as a prerequisite for being considered for employment elsewhere.

“There are a lot of people who don’t want to have that conversation. It’s a tough one to have,” Kogod said. “For future considerations of salary increases, bonus … that’s what people would remember: This person was looking to leave. They’re unhappy here. They’re going to leave anyway, so we shouldn’t give them this next big job.”

Kogod read to the jurors a series of emails and text messages involving the solicitation, or attempted solicitation, of various DaVita workers. He said Thiry used “smart communication” to refer to the non-solicitation agreements in innocuous terms like “ground rules” or “hands off,” the idea being that DaVita executives had to “be careful what you write and what you say.”

During cross-examination, the defense attempted to portray Kogod as disgruntled following his 2016 separation from DaVita. Attorney Juanita Brooks implied that Kogod was motivated to speak to prosecutors because he had a personal axe to grind against Thiry after falling from his own high corporate perch.

“Did you tell them you had a difficult time finding employment in the same industry after leaving DaVita, which you attribute to Mr. Thiry?” she asked.

“I don’t recall that exact conversation,” Kogod said quietly.

The trial continues on Wednesday with the cross-examination of Fanning. The case is United States v. DaVita, Inc. et al.