White-collar DaVita trial kicks off with competing interpretations of corporate agreements

Twelve jurors heard competing interpretations on Monday of the corporate agreements that are at the heart of a novel criminal trial based on an 1890 federal antitrust law.

To the government, the agreements between kidney dialysis company DaVita, Inc. and three of its competitors represented an illegal scheme to restrict the movement of employees between healthcare companies, fueled by ex-leader Kent Thiry’s unquenchable desire for control.

“This is a case about a corporate CEO who wanted control of his employees. Not just control over how they did their job, but control over what opportunities they got and whether they got to leave the company,” said Megan S. Lewis, an assistant section chief with the U.S. Department of Justice. “You’ll see that Kent Thiry knew exactly what he was doing. You’ll see him make the same demands again and again from competitor after competitor.”

But DaVita argued that, whatever jurors may feel about Thiry himself, the agreements did not suppress the competition for DaVita’s employees.

“What you won’t see anywhere in the evidence is the only thing that could make any of this a crime: a market allocation agreement. A conspiracy and agreement to allocate the market for these employees and prevent meaningful competition for these employees in the market,” countered John C. Dodds, an attorney for DaVita.

The opening statements from attorneys kicked off the prosecution of DaVita and Thiry by the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division. At stake is a unique interpretation of the 132-year-old Sherman Antitrust Act which, broadly, outlaws unreasonable agreements that restrict commerce. According to the government, the informal understandings between DaVita and three of its competitor companies not to proactively recruit DaVita employees amount to a Sherman Act violation.

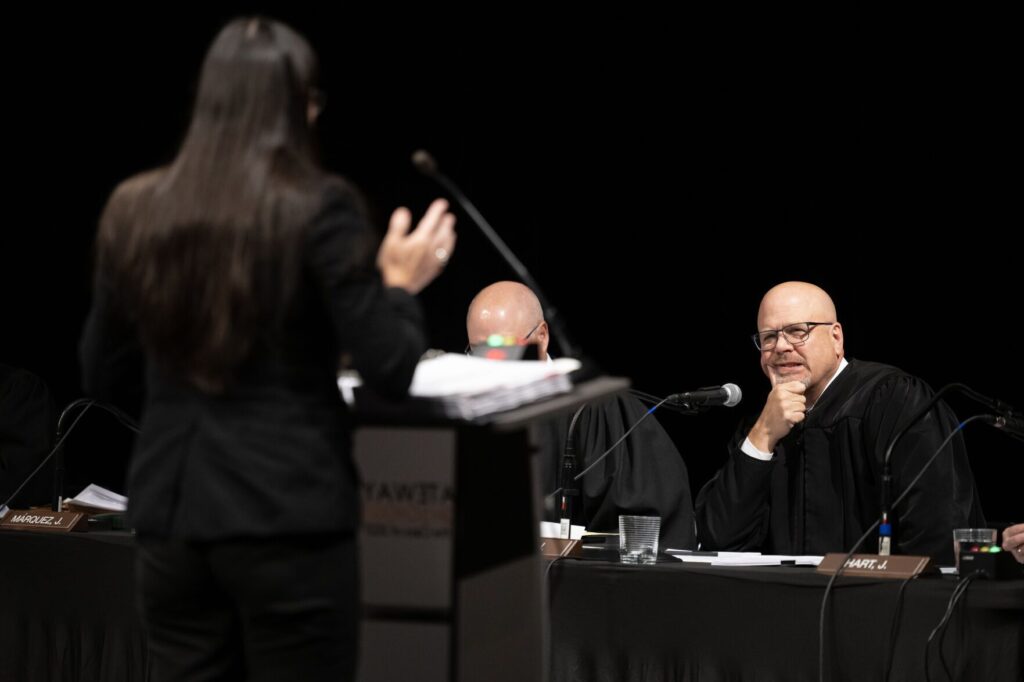

Forty-two men and women were summoned to the U.S. District Court in downtown Denver to serve as potential jurors in the closely-watched trial. U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson quickly dismissed multiple people based on their admitted ability to be impartial.

“I have a strong opinion about Mr. Thiry. I actually lost my home when my husband was fired by him and we had to move,” a retiree acknowledged during jury selection.

“Are you telling us that you could not be fair to the defendants in this case?” Jackson asked her.

“I have strong opinions,” she responded, prompting the judge to dismiss her.

DaVita is a Fortune 500 company based in Denver that employs roughly 67,000 people. Thiry was its leader from 1999 to 2019 and was simultaneously a political player, donating roughly $5.9 million to state ballot initiative campaigns since 2011 and backing the creation of the independent redistricting commissions that drew legislative boundaries following the 2020 census.

Between approximately February 2012 and June 2019, the government alleges that Thiry made a series of agreements with three of DaVita’s competitors: Surgical Care Affiliates, Hazel Health and Radiology Partners. The companies, each run by a former DaVita executive, agreed not to solicit DaVita employees. As part of the agreements, workers were required to tell their DaVita bosses if they were being considered for a position elsewhere.

During opening statements, Lewis claimed that the agreements were in service of Thiry’s own ego.

“Losing employees was bad for business, bad for DaVita’s reputation and bad for Kent Thiry’s reputation. Kent Thiry found it personally embarrassing. It wouldn’t look good if people left his company to go to his competitors,” she said.

In January, Jackson declined to dismiss the criminal charges against DaVita and Thiry. With this being the first time a non-solicitation agreement is prosecuted as a Sherman Act violation, the government will need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt not only the existence of the non-solicitation agreements, but also that DaVita entered into them with the intent to allocate the labor market.

Lewis promised the jury would see text messages and emails illustrating the formation of the conspiracy, plus testimony from former high-level DaVita employees showing the intent of the non-solicitation agreements was to stop workers from leaving.

“You’ll see that Kent Thiry knew he was restricting competition because you’ll see Kent Thiry’s own words,” Lewis said. “Instead of competition in the free market, he conspired with his CEO friends to allocate the market for employees.”

The defense cast doubt on the government’s evidence, claiming DaVita could hardly allocate the market by making deals with just three of the hundreds of companies from which DaVita regularly recruited employees. Dodds also preemptively attacked the motivations of the government’s cooperating witnesses.

“Their lives could go in two directions: One direction could take them over here, sitting with us as defendants in this case,” he said. “The other direction could take them to that witness stand – and when they’re done testifying, take them out the door to freedom and the rest of their lives.”

During voir dire, the part of jury selection where the parties ask questions of potential jurors, the defense inquired at length about the jurors’ impressions of healthcare companies, CEOs and the jurors’ desire for more stringent corporate regulation. One woman indicated she was inclined to think that if Thiry was in court, he had done something wrong.

“I don’t have the FBI showing up at my house because I’m not doing anything that would result in that attention,” she said. Multiple jurors agreed with her.

Jackson indicated he would not seat an alternate juror, meaning it was crucial that the 12 members of the jury could commit to the duration of the trial. He ended up dismissing prospective jurors who already had bitter feelings towards DaVita or had strong opinions about companies restricting hiring from their competitors.

The defense did not dispute that the non-solicitation agreements existed, but insisted that the context would show an intent to foster corporate collaboration. The agreements allegedly were a means for DaVita to compete to retain employees who were thinking of leaving by offering them promotions or raises, rather than deterring them from taking other jobs.

“How can we make you happy and keep you here?” Dodds said was DaVita’s approach to the agreements.

If convicted, Thiry could be sentenced to up to 10 years in prison for each of the three counts, while DaVita could pay up to $100 million in fines per count.

The trial is scheduled to last up to three weeks. Originally, it was set to begin on March 28, but it encountered a week’s delay after one of the participants contracted COVID-19. Prior to the jurors’ entrance, Jackson acknowledged to the parties that it was he who tested positive.

The case is United States v. DaVita, Inc. et al.